The Collectors

It was in early 1976 that I met Jane and Richard Lang because of a passing conversation with Robert Motherwell. During a symposium I had organized at the Washington State University Museum of Art in Pullman the preceding fall, Motherwell mentioned he would be stopping in Seattle to visit with some collectors he quite liked. They had recently bought a second great painting of his, Irish Elegy (1965), and he thought I should see their collection. In a subsequent telephone call, Jane Lang breezily noted that Motherwell had spoken of our meeting and campus visit, and that she would be delighted to make a date “between Hawaii and New York” for me to see their collection. Arriving at the Langs’ door on the appointed day, I was met by a vivacious and welcoming woman who quickly put aside all formality. We spent the two-hour visit talking enthusiastically about the artworks that commanded the walls of their elegant, light-filled home (fig. 1).

On that first viewing, the quality and impact of the collection, centered on a core of New York School painters, was exhilarating. Two powerful Motherwell paintings were indeed hanging in the company of singularly beautiful canvases by Franz Kline and Clyfford Still, along with the surprise of three important works by European artists Francis Bacon and Alberto Giacometti that signaled an independent, personal criterion at work. The strength of every work in the collection, coupled with the lack of the usual peripheral “filler” artworks, spoke volumes to me about the intention of these collectors. Richard Lang’s appearance near the end of the visit clarified the joint nature of their collecting activity. Our conversation confirmed for me how much the balance of Jane’s obvious knowledge and passion for art with Richard’s rigor and clear distrust of the fashionably predictable drove their shared search for the very best. It was a visit and dialogue that I would relish and repeat again and again over the ensuing years as our relationship developed along with their collection.

Hired in the fall of 1979 as the curator of contemporary art and second head of the Modern Art Department of the Seattle Art Museum, I was able both to gain a better understanding of how this singular, focused collection began and to observe the Langs’ collecting activities firsthand. The start of the collection was clearly rooted in who they were as individuals, their interest in contemporary art ignited by the people the couple had come to know in Seattle who drew them into an important transition period for the community and its museum.

Introduced in Hawaii in 1965, Jane (née MacGregor) and Richard Lang fell in love and would marry in 1966. After her move to Seattle, as was Jane’s nature, she threw herself into exploring her new community and pulled Richard along into the city’s rapidly evolving contemporary art scene. It was a community that had historically focused on the Northwest regional painters and its university-based artists. The city’s museum—established and built primarily to house a private Asian art collection—was slow to expand its programming beyond the interests of its founder/director, Dr. Richard E. Fuller, and the limitations of its Volunteer Park building. The 1962 Seattle World’s Fair—Century 21 Exposition—had literally introduced the region’s citizens to the world, and one of its art exhibitions, American Art since 1950, became a local cause célèbre in its presentation of challenging new abstract painting. A local group of early collectors of modern and contemporary art, including Saul Schluger, Anne Gerber, Bagley and Virginia Wright, Samuel Rubinstein, and John Denman, occasionally met socially in one another’s homes to hear a visiting contemporary art dealer or share their latest acquisitions with like-minded people. Inspired by the World’s Fair, they decided to formalize their activities in 1964 through incorporation as a private, by-invitation group under the aegis of the museum. The Contemporary Art Council (CAC) would sponsor lectures, symposia, and visiting artists for the education of their membership and the broader community, and would periodically sponsor or organize contemporary art exhibitions for the city as part of the museum’s public program.

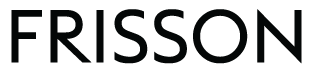

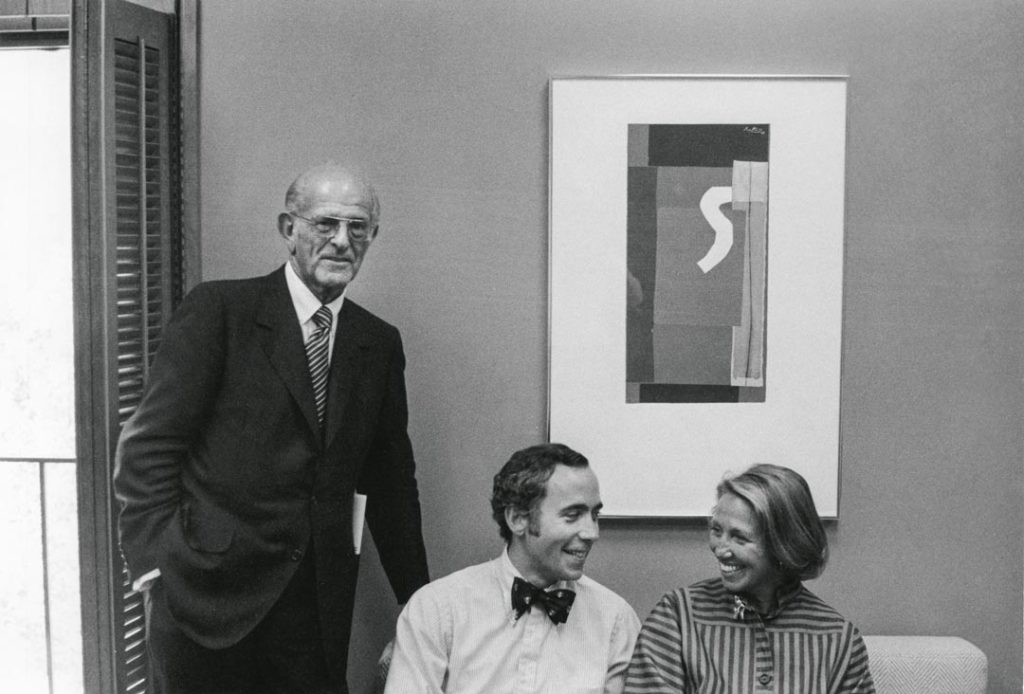

The Langs’ involvement with the council, which Jane formally joined in 1970 (fig. 2), introduced them to this expanding community and gave them the opportunity to see and discuss the art being acquired in Seattle. CAC programming, through the national contacts of active collectors like Bagley and Virginia Wright, provided access to an impressive stream of prominent art dealers, artists, critics, and curators who opened up the latest contemporary art ideas and criteria, both in public appearances and in the council’s private social evenings held in members’ homes. Jane Lang described the impact of the discussions and events of those early days of camaraderie and discovery with the CAC. She credited the close friends that she and Richard made there, like the Wrights and Robert Dootson, with encouraging and emboldening them to collect. An astute businessman with a law degree from Stanford University, Richard Lang found learning the new language of art and the mechanics of the art marketplace stimulating. He was more than intrigued by the question of what constituted a great work of art, what defined a contemporary masterpiece. And so, inspired by their CAC activities and introductions to Gotham’s art scene, the Langs’ business and pleasure trips to New York began to change, with visits to galleries and museums added to the usual theater and ballet evenings on their itinerary.

With the construction of their new home on Lake Washington in 1970 (fig. 3), Jane recognized an opportunity to begin seriously collecting and proposed they look around New York that fall and perhaps buy a “painting for over the couch.” It was clear from things Richard said in the often-recounted story of their first purchase that a painting was a negotiated compromise from his vision for their new home as one with stylishly empty walls and a view of the water. Franz Kline’s magisterial Painting No. 11 (1951) “for over the couch” (fig. 4) was a remarkable first purchase and a life-altering event, both setting a direction for the couple’s collecting over the next twelve years and establishing an exceptional standard of quality for any work that would come into their home in the future. The Kline was Richard’s choice, and it remained his favorite for the rest of his life. Painting No. 11 is a powerful abstraction with a linear structure of black brushstrokes defining and containing white blocks of paint, which seem to have materialized in the artist’s repeated campaigns with the brush across the surface. These dense slabs of white pigment reveal the pentimenti of their forming and the drips and shadows of the black line’s struggle to limit the slabs. Richard once observed that until he saw that Kline canvas, he did not know a painting could affect him so physically, that it could wordlessly take over his imagination. He was enthralled by his experience with Kline, and the couple would go on eventually to acquire an additional eleven of the artist’s works on paper and earlier paintings.

Over the next three years after purchasing the Kline, the Langs abandoned all thoughts of empty walls as they sought out and bought five major museum-quality works by exponents of American Abstract Expressionism, signaling to their Seattle friends and to the New York art world the couple’s commitment to building a first-tier collection. The next two paintings they acquired, Untitled (1963) by Mark Rothko and Before the Day (1972) by Robert Motherwell, share a number of formal qualities with the Kline canvas—a severely restricted palette, a strong, clear composition, and an emotionally potent paint surface characteristic of each artist’s mature style. Reputedly the last canvas sold by Marlborough Gallery from Rothko’s estate before it was sealed in a legendary five-year legal battle, the large, signature Rothko canvas is darkly brooding and, like the Kline, is not an easy work for many people to approach. Rothko used shadowy gradients of transparent and translucent pigments applied with brush and paint-soaked rag to create a series of four stacked rectangles that optically recede and advance in perceptual space, slipping from solid to void. Its closed and somber austerity has always struck me as a surprisingly tough choice for these lively new collectors. The Rothko evokes the meditative, enveloping silences of the night, whereas the Motherwell, one of his Opens, purchased during a studio visit, is filled with bright possibility. In the reflected and refracted light from its brush-activated surface, warm and cool whites, sooty grays, and sharp black lines animate both the field and an aperture rich with associations.

In close succession in the fall of 1972, the Langs then purchased a graphically dynamic Adolph Gottlieb canvas from his Burst series, Crimson Spinning #2 (1959). The expansive canvas’s white field barely contains its two stacked orbs—a compressing, optically pulsing alizarin crimson oval over an explosive black frenzy of spattering brushstrokes challenging the work’s balance. Its hieratic power is like a sharp cracking sound on the wall compared to the enveloping silence of Rothko’s 1963 masterpiece.

The collection’s early chromatic austerity shifted in 1973 with the acquisition of two works that revel in color and extend the painterly vocabularies represented among the Langs’ holdings. An important early Clyfford Still canvas, PH-338 (1949), presents a rich record of the artist’s brush and palette knife caressing and cutting across the canvas’s expanse in a continuous, densely brushed, impastoed field of smoldering red paint. Eruptions of an earthy sienna and deep black, highlighted by molten notes of a sharp yellow or vermilion, fracture the surface. This compelling painting embodies both vast distances and an intimate immediacy in its horizonless sweep. A rarity in private collections due to the artist’s early withdrawal from the marketplace, this beautifully mysterious painting is a singularly important work within the Lang collection. In contrast to the Still’s opaque physicality, the graceful Helen Frankenthaler work chosen by the Langs, Dawn Shapes (1967, fig. 5), is a fluid, directly worked composition of brushed and dragged washes of transparent and opaque acrylic. Pooling pigments tease out shapes and lead the viewer’s eye across a coral-framed threshold into the canvas center with its roiling, circling ochre overtaking a shadowing sage green. Balancing the spontaneous with the deliberate, the Frankenthaler is a vital open work that brings her pioneering direct-action methodology into the dialogue. Auspiciously anchoring the collection’s focus and future, these six massive works represent artists at the center of Abstract Expressionism in New York. Taken together, the canvases evince the Langs’ confidence as collectors and their willingness to risk waiting for works of the finest quality that embodied the essence of an artist’s contribution to the movement’s development.

In just four short years, the Lang Collection was on the art world’s must-see list in Seattle, and Richard had agreed to join the Seattle Art Museum Board of Trustees. Thanks in many ways to the CAC activities that introduced them to artists and ideas, Jane and Richard had developed a comfortable process for identifying and evaluating artists with whom they both connected emotionally. They were also finding the people in New York who could help them further refine their eye and hone their choices to realize the couple’s vision. Their twice-annual trips to New York had taken on a more complex character as the search for artworks plunged them headlong into the New York scene where they would become virtual fixtures (fig. 6). As a couple, Jane and Richard thrived on the insider world of attending gallery and museum openings and gala parties, meeting artists, and interacting with museum professionals and other committed collectors with whom they could share their new passion. A warmly gregarious and outgoing person, Jane quickly made friends across the art scene through galleries, museum events, and travel.

The Langs joined the International Council of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in 1973 and became founding members of the National Committee of the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1980. In recounting their New York visits, Jane once shared that Richard was such an inveterate competitor, so energized by their encounters with dealers and fellow collectors, that he would want to spend hours at the end of the evening discussing and comparing what they had seen with their own works. He had become an avid collector, using every opportunity to deepen his knowledge of art and the marketplace to sharpen his judgments.

The growth of the collection shows the clear imprint of those spring and fall sojourns in New York, with the dates that artworks entered the collection closely mirroring the Langs’ trips to the East Coast. I always relished the first phone call with Jane when she returned from New York, as did many people in Seattle, for the generous, ebullient tumble of exhibitions seen, theater tips, and art-world news and gossip. We would then get down to the discussion of which dealers had shown them what paintings, what she and Richard had thought of them, and what work would be finding its place on the walls of their Seattle home. Like a pebble dropped in a quiet pool, Jane would share her enthusiasms and most recent discoveries with a swath of people across the broader art scene—ballet, theater, music, and visual arts—to inspire and challenge them. Those calls from Jane had a surprisingly tangible effect on the community, frequently sparking new discussions and projects with the Langs’ support. And then, when each new work arrived, Jane would issue a much-coveted invitation to a few close art friends for a first viewing to celebrate and discuss the latest arrival.

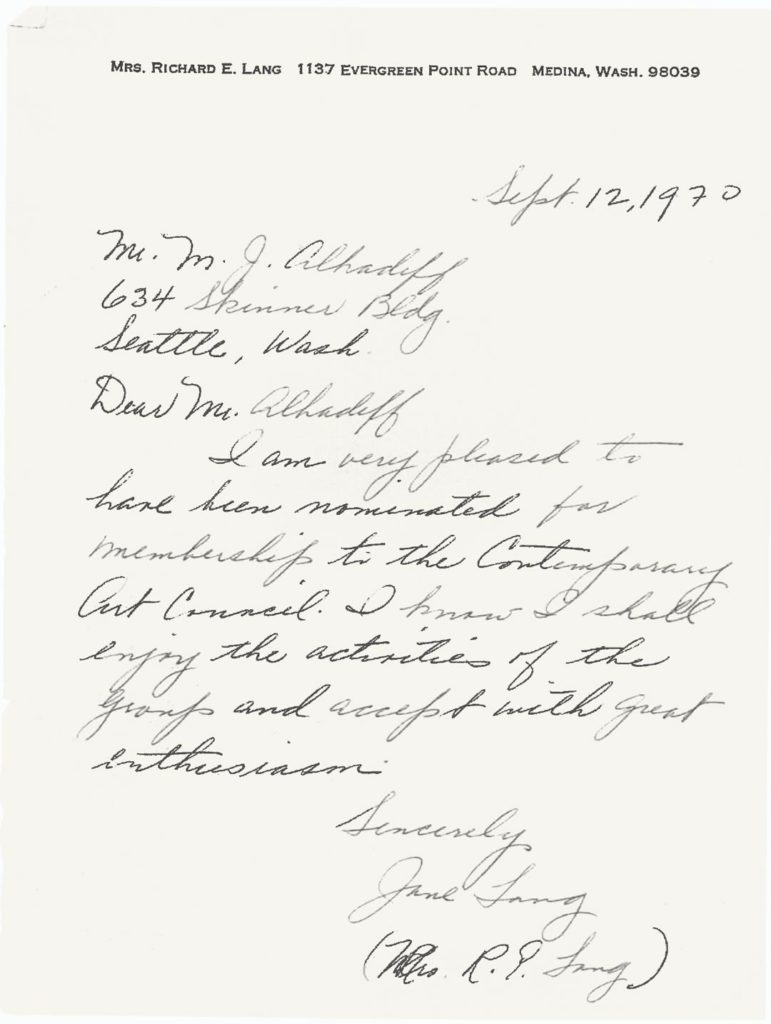

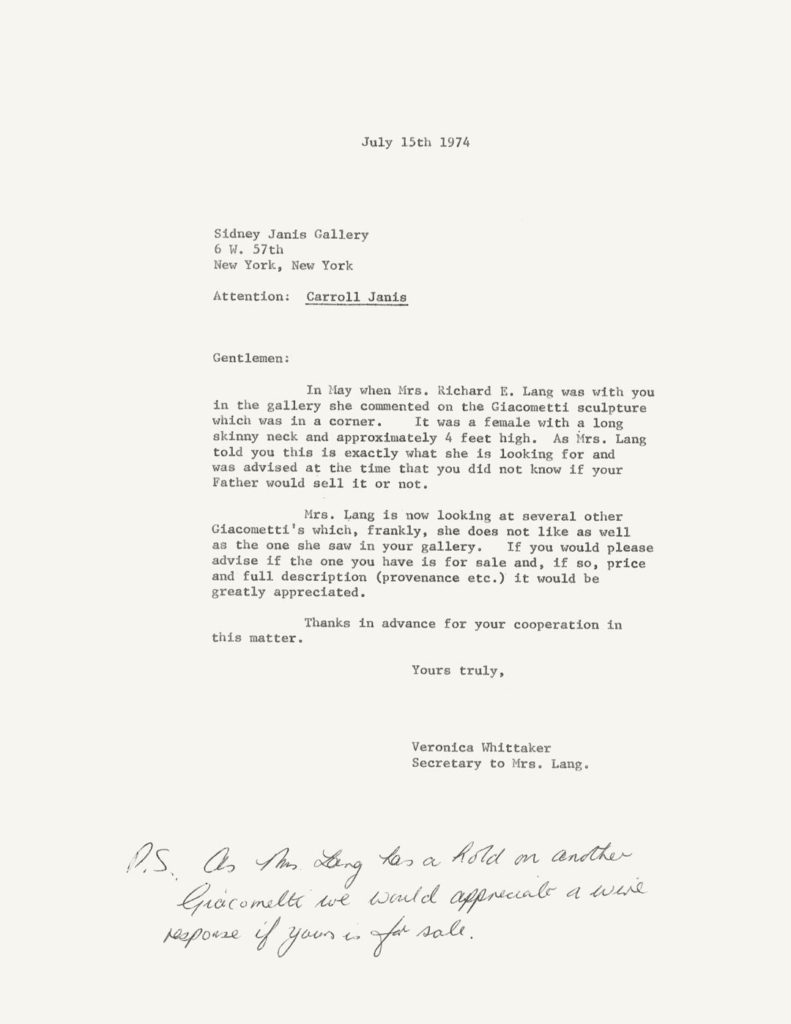

The Langs’ criteria for collecting only works that expressed a strong, individual vision to which they both responded brought the addition of figurative works to the collection’s core of Abstract Expressionist paintings in the mid-1970s. New acquisitions from two of the most eminent postwar European artists—Francis Bacon and Alberto Giacometti—introduced specific subject matter, enriching the experience and understanding of expressionism offered by the collection. Richard was particularly moved by Bacon’s power to communicate the emotional emanations of personality in his often-radical rendering of the figure, the peeling away of decorous signifiers to suggest underlying psychological truths in paint. Offered an opportunity to acquire Portrait of Man with Glasses I (1963) at auction and then Study for a Portrait (1967) from his dealer friend David McKee, Richard acted, the deals were struck, and the works found their way to Seattle—causing quite a stir at the time as the first Bacon paintings in the Northwest. When Jane saw a cast of Giacometti’s epochal Femme de Venise II (1956) in the back room at Sidney Janis Gallery in May 1974, she was convinced its evocative surface and timeless presence had to be part of their lives and the collection; the task of convincing Janis to relinquish his personal bronze fell to Richard in a series of letters and calls that prompted a swift affirmative when Jane’s secretary formally requested the work in July (figs. 7, 8). His success brought this beautiful example of Giacometti’s most important series of female figures to Washington (fig. 9). Memorably, after installing and living with the work a while, Jane noticed to her delight one afternoon that the setting sun transformed the attenuated figure’s normally pencil-thin shadow into a voluptuous avatar stretched across the wall behind it. A story she enjoyed recounting for visitors to the collection, it was also an example of why I loved giving art groups tours of the Lang Collection with Jane over some thirty years. The directness of her response to the works, coupled with the personal, anecdotal context of discovering them, was so refreshingly immediate and informed. And she never tired of my drawing ever-larger art historical circles around groups of works and methods, illuminating the through lines of ideas that connected the works.

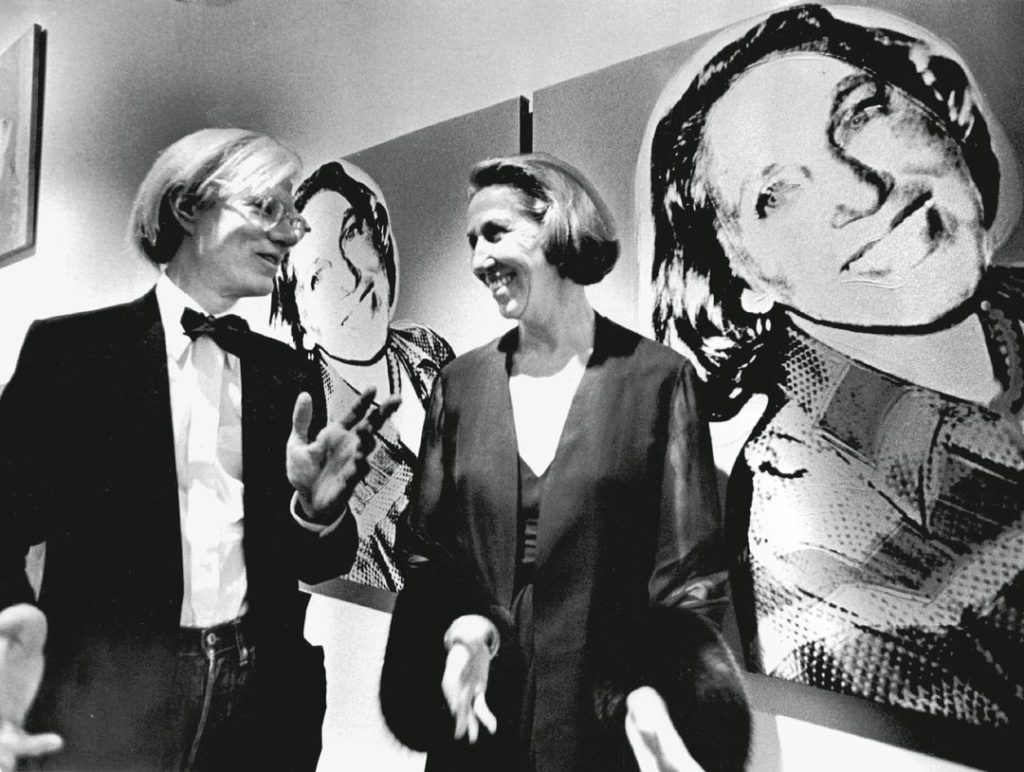

Thanks to the programming and growth of the CAC over the preceding decade, the Seattle Art Museum established its Modern Art Department in 1974 with the council’s support, designating its Seattle Center facility as the Modern Art Pavilion and announcing the hiring of Charles Cowles as the museum’s first curator of modern art. Though without actual curatorial experience, Cowles brought to Seattle his network of connections as the publisher of Artforum, a who’s who of the New York art world, to kick-start the program; his presence energized the community with the promise of future possibilities. As a collector himself, Cowles was a generous and eager collaborator for the Langs. He proved to be particularly helpful in 1976, when Richard decided to surprise Jane for her birthday with her portrait by Andy Warhol, whom they had met in 1973 in San Francisco. Cowles was negotiating one of the major acquisitions of his tenure at SAM—Warhol’s Double Elvis (1963)—with the intention of staging an exhibition around his purchase, and he was delighted to assist a museum trustee while enhancing his position with the Warhol studio. The exhibition concept would expand to incorporate a group of Warhol’s recent works and society portraits, including the special birthday surprise for Jane that Cowles was helping to arrange. In gratitude to the museum for the enterprise’s success, the Langs donated one panel of the portrait following the exhibition (fig. 10; see page 27).

As a ploy to engineer the necessary Polaroid sitting at Warhol’s studio in New York to capture Jane’s likeness for her portrait, Richard told her he was the portrait subject. So it was no surprise when, a few months after the unveiling of her portrait, Jane brought up commissioning an actual portrait of Richard. The Langs then discussed the Warhol portrait idea with their friend David McKee, who responded, “Dick’s too ornery to be painted by Warhol. You need somebody who can really catch him.”1 Richard revealed his long-held dream of having Francis Bacon do his portrait. McKee, who had a relationship with Bacon going back to his days at the Marlborough Gallery, rather quickly disabused Richard of the possibility of Bacon taking on the commission. Instead, he suggested the American painter Alice Neel, who after a 1974 Whitney Museum retrospective was becoming more prominent for her tough, uncompromising portraits. Intrigued, the Langs did some research, met the artist, and chose to have her paint the portrait of Richard in 1978 (see page 29), which brilliantly captures the man and the dynamic encounter between sitter and artist. “Jane took a chance,” McKee recalled, “and she loved the portrait. And Dick loved Alice Neel. They were two ornery people who got along famously.” Together, the Lang portraits in the context of the collection both provide a vibrant reflection of the collectors’ personalities and illuminate the poles of formal invention, from expressionist abstraction to the flat, mechanical surface of Pop Art, represented in the collection.

In 1976, while the subterfuge around the commissioning of Jane’s portrait played out, the Langs added Bacon’s Study for a Portrait to the collection, along with a quietly enticing monochromatic Willem de Kooning painting. Town Square (1948) was purchased from Ben Heller, an early and influential collector of Abstract Expressionism and fellow member of MoMA’s International Council, who had become an adviser and friend to Richard; similar personalities, both were tough businessmen, curious, and opinionated. Part of a seminal group of late-1940s paintings that launched de Kooning’s career, Town Square is a work in continuous visual flux. De Kooning played a bold, brushed line off of elusive shapes as they coalesce into momentary forms that open and close the field, suggesting motion and the passage of time in both method and the resulting painting. It is a work that foreshadows the powerful gestural paintings that changed the course of American abstraction and assured de Kooning’s place in its pantheon.

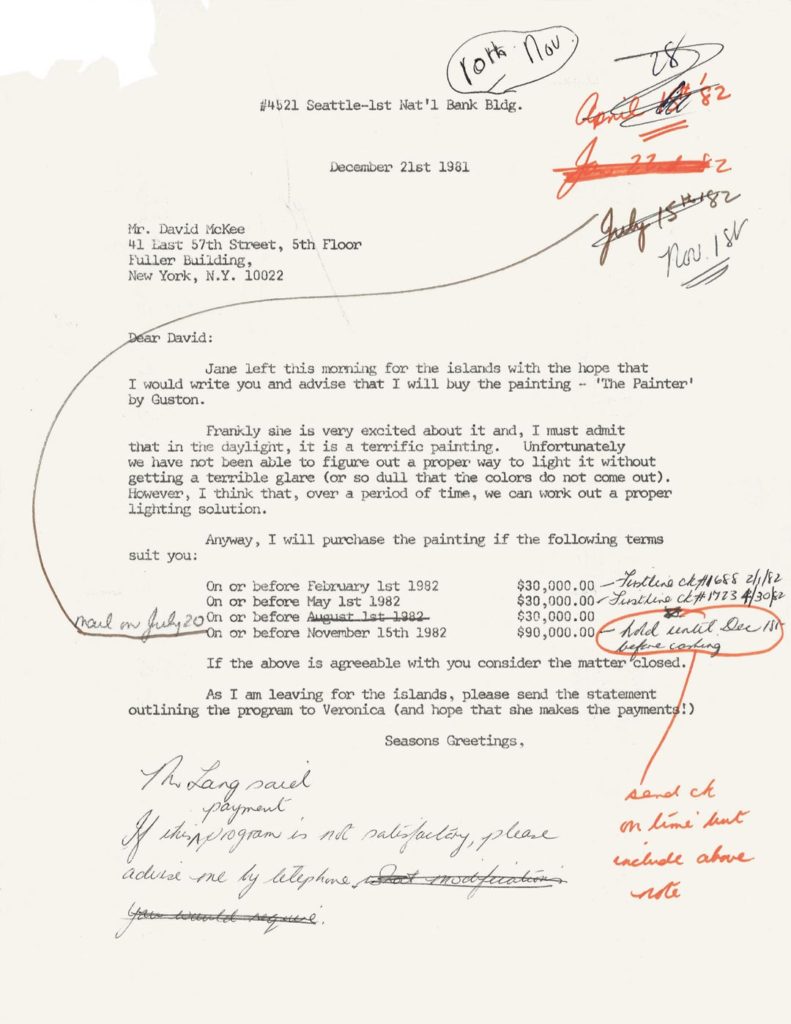

The de Kooning presaged the Langs’ engagement with artists who attacked the canvas directly—exploring, putting down, and removing paint in the battle to discover the spirit and inscribe the form of the work. Jane led the acquisition of major mature works by Joan Mitchell and Lee Krasner for the collection, buoyed in part by the emerging scholarship in the late 1970s on these women’s contributions to Action Painting. The fluid trails and swirling knots of spontaneously brushed oil paint set into motion Mitchell’s The Sink (1956), a lyric painting filled with the echo of observations and memories of places in the artist’s past, which have taken form in a deeply personal vocabulary of mark and color, gesture and surface. It often elicited from Richard a comparison to his beloved view of Lake Washington. Lee Krasner’s monumental Night Watch (1960) is a masterpiece of gestural abstraction in which the full-arm strokes that define and animate the surface create a powerful, mysterious place. Engaged by Jungian theory and the view that painting is an act of discovery and revelation, Krasner opens imagination’s door to a nocturnal place of all-seeing eyes. The Krasner and Philip Guston’s heroic self-portrait The Painter (1976)—for me, one of the great works of Guston’s long career—were the last paintings that Jane and Richard would buy together. As I witnessed it, they were complicated pictures for Richard to embrace emotionally, even as he understood their importance intellectually and finally agreed they should be in the collection. Writing to David McKee to secure the Guston, Richard noted, “Frankly [Jane] is very excited about it,” and conceded, “I must admit that in the daylight, it is a terrific painting” (fig. 11). The two paintings came to live on opposite walls in Jane’s office (fig. 12), where they never failed to stop even the most sophisticated visitors in their tracks with the power and intensity emanating from those canvases.

By the late 1970s, even as they continued to make judicious acquisitions for their own collection, the Langs found ways to integrate art into their philanthropy beyond Seattle. In 1979, in an act of generosity that anticipated later gifts, they supported the acquisition of an Alexander Calder sculpture for the campus of Richard’s alma mater, Stanford, and commissioned a painting by Robert Motherwell to celebrate their endowment of the university’s Richard E. Lang Law Chair (fig. 13). The spring of 1982 brought an important opportunity for the Langs to share their collection when MoMA’s International Council visited Seattle and Vancouver, British Columbia. Virginia Wright and Jane Lang organized the council’s crowded tour itinerary of public and private arts venues, including a collection tour and special luncheon at the Langs’ home. The council members were awestruck by the focus and quality of the collection they discovered inside the plain white stucco walls of the modest-looking house. Adjourning to the yellow-and-white-striped tent set up on the lawn with perfectly framed views of the lake and of David Smith’s sculpture Cubi XXV (1965) set against a wall of evergreens, the sixty attendees were feted with a spectacular Northwest seafood buffet. It was Lang hospitality at its finest—lovingly characterized by one of the attendees as “a feast to end all feasts.”2

Richard Lang died in November 1982 as we were planning the first public exhibition of the collection, at the Seattle Art Museum, for early 1984. The exhibition was the outgrowth of over five years of conversations I had had with Richard and Jane about the future of their growing collection and the part it could play in the Seattle Art Museum’s projected new building in the heart of down-town Seattle. Before Richard died, we had agreed to a preliminary checklist and assigned the exhibition a slot on the museum’s schedule, with the mutual understanding that the exhibition was part of the concerned parties’ desire to forge a plan for the future public life of the collection. I worked with Jane to finish the exhibition, which showcased a selection of forty-four works. It opened to acclaim and surprise in the region, which had not realized the depth and quality of the collection, even though the Langs had generously lent works to museums throughout their collecting lives. The exhibition and publication celebrated the collection, which encompassed works by fourteen first-and second-generation Abstract Expressionists, as well as two European contemporaries, with seven artists represented by small clusters of important works from across their careers.3 As Jane explained to a member of the press at the opening, they had chosen to live with their collection and only buy as many works as their home in Seattle could accommodate; this led the Langs to focus early, remodel twice, and continually broaden and deepen the collection with additional fine examples of each artist’s work. Their passion for quality was what most distinguished the Langs’ acquisitions and separated theirs from larger private collections. As was clear in the 1984 exhibition and remains true in the present one, virtually every work is an aesthetic summary of the artist’s contribution to the course of postwar contemporary art as we understand it today.

Serious, passionate collectors, the Langs assembled a rare trove of art to enhance their life together, to live with beauty and greatness, and to enrich their community’s cultural resources. The transformative gift to the Seattle Art Museum of nineteen remarkable works from the Richard E. Lang and Jane Lang Davis Collection is a fitting legacy for this extraordinary couple and their love of Seattle.

Author

Bruce Guenther, a specialist in European and American postwar art, was chief curator and curator of modern and contemporary art, Portland Art Museum, Oregon, until his retirement in 2014. He previously was chief curator of the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, and head of the modern art program at the Seattle Art Museum. His recent publications include essays for Paper: Charles Arnoldi (Radius, 2017), Michael C. Spafford: Epic Works (Lucia | Marquand, 2018), and Roland Peterson: Works on Paper, 1956–2005 (Studio Shop, LP, 2019).

Notes

1 David McKee, in conversation with Carol Vogel, January 2021.

2 Carol Coffin, executive director of the International Council of the Museum of Modern Art, in conversation with Carol Vogel, January 2021.

3 Bruce Guenther and Barbara Johns, The Richard and Jane Lang Collection (Seattle: Seattle Art Museum, 1984). In addition to works by the artists represented in the Friday Foundation’s 2021 gift to the Seattle Art Museum, the exhibition, which was on view February 2–April 1, 1984, presented works from the larger corpus of the collection, including a major late painting by Hans Hofmann and the Lang portraits by Andy Warhol and Alice Neel.