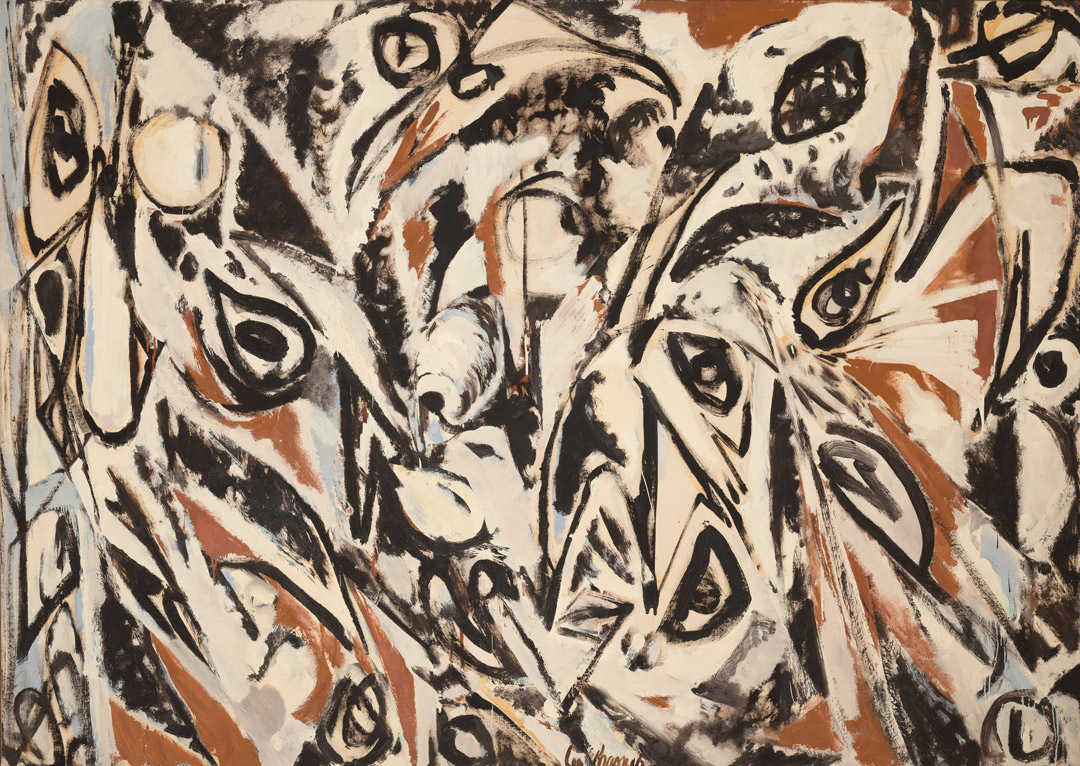

Painting No. 11

FRANZ KLINE

Painting No. 11, 1951, Franz Kline, American, 1910–1962, oil on canvas, 61 1/2 x 82 1/4 in., Seattle Art Museum, Gift of the Friday Foundation in honor of Richard E. Lang and Jane Lang Davis, 2020.14.12, © Artist or Artist’s Estate, Courtesy of the Friday Foundation.

“The only worlds of art America has given are her plumbing and her bridges.”

–Marcel Duchamp1

One horizontal and two verticals, both black, stand amid an off-white field. These elements span dimensions – slightly more than five feet tall by exactly seven feet wide – neither diminutive nor epic. Rather, they combine a certain intimacy with a monumental aura. The oil pigment layers range from a thinness that exposes the underlayer (notice where the rightward vertical terminates near the canvas’s lower edge) to sufficiently thick to record the housepainter’s brushstrokes. In various passages the medium self-destructs, as it were, into splatters, streaks, scrapes and scumbles. Overall, the image has a quick, head-on impact – as any apparent gestalt should. However, an alert gaze may find that the general configuration could be the skeletal semblance of a table or some similar quotidian, household object. However, everything thus described requires immediate qualification, as though what looks obvious is not.

For a start, the “horizontal” tilts a bit downward, making it more accurate to consider this rule a slight diagonal. It also splinters into two or three segments. Two for sure, given its rupture at the far right. Ambiguously, three, because to the left of center the line crumbles into a trace resembling a faint after-image compared to the much denser black parallel band above. Likewise, the verticals are less than foursquare,2 not to mention that each stops or fades as it nears the composition’s edges. Neither are “black and white” quite the correct labels. All the white is palely mottled – greyed by its opposite color, while it make inroads upon this selfsame black. “Grisaille” sounds more apt, though even then there lurks a second hue, an almost subliminal creamy tone. Pentimenti and blurs also prevail that are inimical to a true gestalt. Nor is this really any old table unless, perhaps, conjured by imagination – which it teases, so to speak, to identify it. At the end of the proverbial day, Painting #11 puzzles the viewer.

Puzzlement is one explanation for why Painting #11 demands such detailed description. Puzzles also have another knack. To solve puzzles (successfully or not), sharpens the faculties. They make us look or think again – which is what Franz Kline’s mature art does. Certainly, Kline’s pictorial strategies are not “about” the phenomenology of perception (to recall Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s famous 1945 account of seeing, knowing and feeling).3 Nevertheless, they grab our attention in a phenomenological way, a mode entailing a level of scrutiny that alters mere looking into apperception. As the French philosopher explained, the task is “to reawaken perception and foil its trick of allowing us to forget it as a fact and as perception in the interest of the object which it presents to us.”4 Simply stated, what a sentient spectator gets in front of a quintessential Kline such as Painting #11 involves not just “understanding” (mind) or even “seeing” (vision) per se. Instead, it evokes more an encounter where the two blend into a single experience that feels as vivid as it proves hard to verbalize. Art historian Irving Sandler had this kind of awakening when he happened upon Kline’s Chief (1950) at the Museum of Modern Art in 1952. Probably it applies to many of those who admire Kline too.

Sandler’s recollection simplifies matters that phenomenology can render unduly difficult to comprehend and therefore merits quoting in full. Pondering on what was it about the picture that astonished and moved him, Sandler wrote: “The painting did not provide any particular pleasure or delight. Nor did I ‘understand’ it. I responded in another way – with my ‘gut,’ as it were. The painting had a sense of urgency and authenticity that gripped me… It was at once surprising, familiar, and imposing… Chief revealed to me the power of the visual in my being. It was like releasing the flood gates of seeing.”5 Even to my own eyes – long jaded by studying Abstract Expressionist artworks over and again – Painting #11 still possesses, seven decades after its execution, a comparable pull. In short, an everyday epiphany. Its oddity lies in an inexplicable power, like coming across some well-worn sentimental object that abruptly sparks diverse memories and associations exceeding or at variance with the sum of its particulars. When the curator William C. Seitz passed his doctoral verdict on Kline in 1955, he observed that the artist “staked everything on single units of black-and-white calligraphy”.6 Seitz got Kline’s means right without mentioning their ends.

Until now I have deliberately focused on Painting #11 in isolation for good reasons. The main one is that Kline’s biography, its effect on his work and status as an Abstract Expressionist have been discussed so often that they have become almost common knowledge – a lore involving facts, factoids, clichés and interpretations well-known enough to need only the most summary retelling here. Indeed Painting #11’s singularity is fresher and outpaces the timeworn art historical narratives surrounding Kline.7

Suffice it to say that as a person Kline was dynamic (he excelled at football in high school),8 witty (he was a dab hand at drawing cartoons), bohemian (he settled in Greenwich Village and was of course a hard-drinking habitué at the Abstract Expressionists’ favored watering-hole, the Cedar Tavern) and macho in a well-established Yankee, America-at-mid-century kind of mould.9 Late in life he owned a black Thunderbird and a silver gray Ferrari. Questioned in 1961 as to whether he regarded himself as an American painter, Kline responded, “Yes, I think so. I can’t imagine myself working very long in Europe or, for that matter, anywhere but New York. I find Chicago terrific but I’ve been living in New York now for twenty-odd years and it seems to be where I belong.”[10 Likewise, Kline maintained a lengthy love affair with his native eastern Pennsylvania: Lehigh V Span (1959-60) typifies his numerous titular allusions to roots (he attended Lehighton High School).11 Now a prime Rust Belt region, in Kline’s youth this hilly landscape spelt raw power: coal, trains, industry, effort and energy.12 Early landscapes such as Palmerton, PA (1941) literally depict this scenery. A lively panorama with a chugging locomotive at its center, the overriding impression is also unkempt. To invoke an American paradigm, the machine disrupts the garden.13

In turn, the literature always discerns the foregoing biographical cues transformed into style and metaphor throughout Kline’s subsequent oeuvre. A typical reading compared Mahoning (1956) with Pierre Soulages’s 23 March ’55 (1955). According to author John McCoubrey, the French painter’s canvas came across as structured, precise, restful and well-crafted. By comparison, Mahoning is called raw, violent, impulsive and restless.14 Stereotypes? Yes. Wrong? No. On the contrary, stereotyping may stem from truth. Furthermore, Kline’s transition from representational to abstract was relatively late and brisk. He considered The Dancer (1946), very influenced by Cubism, his first abstraction.15 Two or three years later a friend, none other than Willem de Kooning, encouraged Kline to project his drawings onto the studio wall with a Bell-Opticon.16 Whatever was once decipherable became estranged. The little grew large. By no coincidence, scale is inherently a somatic sensation. Kline acknowledged that some forms, no matter how effaced, felt figurative to him. Nor is gesturalism or “action painting” conceivable without the body’s agency, which leaves its indexical marks in pigment.17

By 1950 Kline had found himself. In October his first solo show opened at the Egan Gallery. The selection had some of his most iconic achievements, including the ultra-stark Wotan, Hoboken with its circular motif, and the more linear Giselle. Worth noting in the present context is that the output from 1950 and the next four or five years exudes a grainy freshness – Painting #11 has it in spades – that later tended to diminish when Kline’s manner became more rehearsed and, at its least persuasive, slick. The shock of the new outdid its sometimes formulaic replay.

As for the key themes underlying Kline’s iconography, they are those historically equated with American power and facticity. To wit, engineering feats such as the Brooklyn Bridge (often Kline’s structures foster a sense of suspension or torque),18 skyscrapers (New York was Franz’s kind of town), speed as symbolized by railroad engines (Cardinal and Chief both refer to locomotives)19 and motion itself. In fact, Kline’s shapes are always vectors insofar as they either seem forever in flux and/or suggest impending collapse – Painting #11’s shaky armature conveys precarious imbalance.20 And if imbalance sounds antithetical to “power”, think again. Remember how powerful is the oft-shown documentary footage of the Tacoma Narrow Bridge’s juddering collapse in 1940,21 not to mention the explosions that have energized a zillion Hollywood movies from at least the huge gas tank’s immolation at the apocalyptic end to White Heat (1949; dir. Raoul Walsh) onward. In a nutshell, then, Kline redid what had already been the idealized subject of an earlier American movement, Precisionism, in the process ravaging it.

Charles Sheeler’s Water (fig.1) exemplifies the massiveness, concentrated energies, hard angles and cool architectonics that comprise this “technological sublime”.22 Lastly, motion has been an American idée fixe ranging from the quest that led to Plymouth Rock, via Walt Whitman’s “Song of the Open Road” (1855), to Jack Kerouac’s seminal On the Road (1957) and its innumerable cinematic progeny.23 The diagonal in Painting #11 breaks, yet it also continues apace beyond the frame. Lastly, the impersonal, sparse aura to such works links them to the birth of the “cool” in postwar America.24 On the one hand, Kline could wax emotive with his jagged dramas. On the other hand, he was hip enough to make feelings into things, material and matter-of-factual. In a sense, his colliding visual syntax is a “list” of things – encompassing black and white, rectangles, circles, wedges, intersections, and so forth. Nothing is more homespun America than the propensity to make lists.25 The over-abundant attributes that Herman Melville listed to evoke the whitnesss of the whale in Moby Dick (1851) remain a locus classicus for such paens to quiddity. But a rupture with tradition and easy categories now looms. Speaking of which, what happened to the would-be table in Painting #11?.

According to the gallerist Allan Stone, “I raised this question of origins with Charles Egan, Kline’s first dealer, good friend and a pioneer in championing the Abstract Expressionist movement. ‘Tables and chairs,’ was Egan’s answer. ‘Charles, what are you talking about? You’re joking!’. ‘Not at all,’ Charles replied and pulled out a small abstraction, which upon close inspection turned out to be a rocking chair…. Similarly, Egan maintained that the very spare early abstract paintings like Wotan (1950) were inspired by the reduction of tables.”26 This erstwhile homely plot darkens further. Kline’s dynamism hid skeletons in the closet. His father died in mysterious circumstances that may have been suicide. In 1947 Kline portrayed himself as a Red Clown whose mask-like face is tantamount to a pale death’s head.27 The following year or thereabouts witnessed a variant, Large Clown (Nijinsky as Petrouchka): the Russian ballet dancer went insane. Finally, Kline’s path away from realism pivoted around multiple studies of his wife Elizabeth (who had been a ballerina) seated in a rocking chair. In May 1948 Elizabeth was instituionalized. To conclude: the tough, ebullient all-American boy personae hid a darker side to Kline’s psyche. We are nearer film noir territory than the gung-ho arena of “action painting”.

What happened to the tables and chairs is that they became revenants, signs that emit mixed emotions, at once sturdy emblematic icons and sites laden with an uncanny instability.28 There is no dialectic because Kline, unlike Piet Mondrian, suspends dualities. Grids are shaken, certainties blurred (blurs stand midway between directed gestures and the formless).29 Figures and furniture disappeared into force fields. Painting #11 epitomizes this conflict, its complexities embedded within spartan simplicity – as well as an ultimate retort to Marcel Duchamp’s put-down regarding American industrialism (see the epigraph). In Painting #11 and its kin, Kline achieved what some modern thinkers believe is a central purpose in art. That is, to defamiliarize humdrum reality so that we perceive it anew, strange and starkly indelible.30

1 The perhaps ironic or punning title of a 1956 canvas that is neither foursquare nor contains four squares.

2 Maurice Merleau-Ponty, transl. Colin Smith and Forrest Williams, Phenomenology of Perception (London: Routledge Classics, [1945], 2002). To (over-)simplify an often difficult text, Merleau-Ponty’s aim was to reassert the primacy of perception above traditional, Cartesian mind-body dualities.

3 Ibid., p. 66.

4 Irving Sandler, A Sweeper-Up After Artists (New York & London: Thames & Hudson, 2004), p. 10.

5 William C. Seitz, Abstract Expressionist Painting in America (Cambridge, MA.: Harvard University Press, [1955], 1983), p. 165. Pace the fact that Kline himself was not keen on the “calligraphy” idea.

6 The main studies include: Harry F. Gaugh, The Vital Gesture: Franz Kline (Cincinnati & New York: Cincinnati Art Museum and Abbeville Press, 1986); David Anfam, Franz Kline: Black & White: 1950-1961 (Houston: Menil Collection, 1994); Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, ed., Franz Kline 1910–1962 (Rivoli-Turin: Castello di Rivoli Museo d’Arte Contemporanea (2004); and Robert S. Mattison, Franz Kline: Coal and Steel (Allentown, PA: Allentown Art Museum of the Lehigh Valley, 2012).

7 Vawdavitch (1955) references an American football star.

8 The mid-1940s photograph of Kline in Gaugh, op. cit., p. 52, shows a brooding figure in a cut-off check shirt that would still be trendy today and conforms to the “rebel without a cause” personae established by Marlon Brando, James Dean and their kind.

9 Kline (1961), in Katharine Kuh, The Artist’s Voice. Talks with Seventeen Modern Artists (New York: Harper & Row, 1962), p. 153.

10 Absence may also have made Kline’s heart grow fonder for his early days.

11 The railroad in country music echoes in microcosm the mingled pathos and appeal of the railroad writ large. See Norman Cohen, Long Steel Rail: The Railroad in American Folksong (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2nd. ed., 2000). Kline’s imagination accommodated this folksy aspect.

12 Leo Marx, The Machine in the Garden. Technology and the Pastoral Ideal in America (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1964).

13 John McCoubrey, American Tradition in Painting (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, [1963], 2000), p. 4.

14 Gaugh, op. cit., pp. 79-80.

15 Kline’s predilection for monochrome owes a lot, among sundry other sources, to de Kooning.

16 Following the art historian Richard Shiff, himself subscribing to the American philosopher’s C. S. Pierce’s theories, indexicality implies a direct physical contact between an image and its source (for example, a handprint), whereas iconicity instead indicates a visual resemblance between the former and the latter (as in conventional mimesis); Richard Shiff, “Performing an Appearance on the Surface of Abstract Expressionism”, in Michael Auping, Abstract Expressionism: The Critical Developments (Buffalo & New York: Albright-Knox Art Gallery and Harry N. Abrams, 1987), pp. 94-123.

17 Typified by the levitated square and horizontal in Suspended (1953).

18 “Power and freedom” were associated with the railroad at its first appearance in the landscape; Susan Danly and Leo Marx, The Railroad in American Art: Representations of Technological Change (Cambridge, MA.: MIT Press, 1998), p. 46.

19 Cf. Kline, in Selden Rodman, Conversations with Artists (New York: Devin-Adair Co., 1957), p. 109: “To think of ways of disorganizing form can be a form of organization, you know.”

20 The Bridge (c.1955) presents a tangled upheaval.

21 See David E. Nye, American Technological Sublime (Cambridge, MA & London: The MIT Press, 1994). Sandler, in Mattison, op. cit., p. 108, tweaks it to “The Industrial Sublime”.

22 On speed, motion and their relationship to the American 1950s, see Anfam, op. cit., passim.

23 The literature is extensive. Worthwhile starting points are Lewis MacAdams, The Birth of Cool (New York & London: The Free Press, 2001) and Joel Dinerstein, The Origins of Cool in Postwar America (Chicago & London: The University of Chicago Press, 2017).

24 Robert E. Belknap, The List: The Uses and Pleasures of Cataloguing (New Haven & London: Yale University Press, 2004).

25 Allan Stone, Franz Kline: Architecture & Atmosphere (New York: Allan Stone Gallery, 1997), n.p.

26 The “clown” goes back to Walt Kuhn and forward to Wayne Thiebaud. It may denote painting’s intrinsic artifice in an “on with the motley” spirit.

27 A remarkably similar process occurs in William Scott’s art.

28 No mention of the grid is complete without acknowledgment to Rosalind E. Krauss, “Grids” (1978), in ibid., The Originality of the Avant-Garde and Other Modernist Myths (Cambridge, MA & London: The MIT Press, 1985), pp. 8-22. Krauss posits the grid as the foundational modernist pictorial bedrock.

29 The Russian Formalist Viktor Shklovsky coined the concept “defamiliarization” in his essay “Art as Device” (1917). “The purpose of art is to impart the sensation of things as they are perceived and not as they are known. The technique of art is to make objects ‘unfamiliar,’ to make forms difficult to increase the difficulty and length of perception because the process of perception is an aesthetic end in itself and must be prolonged”; Shklovsky (1917), in Alexandra Berlina ed. and transl., Viktor Shklovsky: A Reader (London: Bloomsbury, 2017), p. x.

David Anfam

© Art Ex Ltd 2021