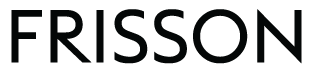

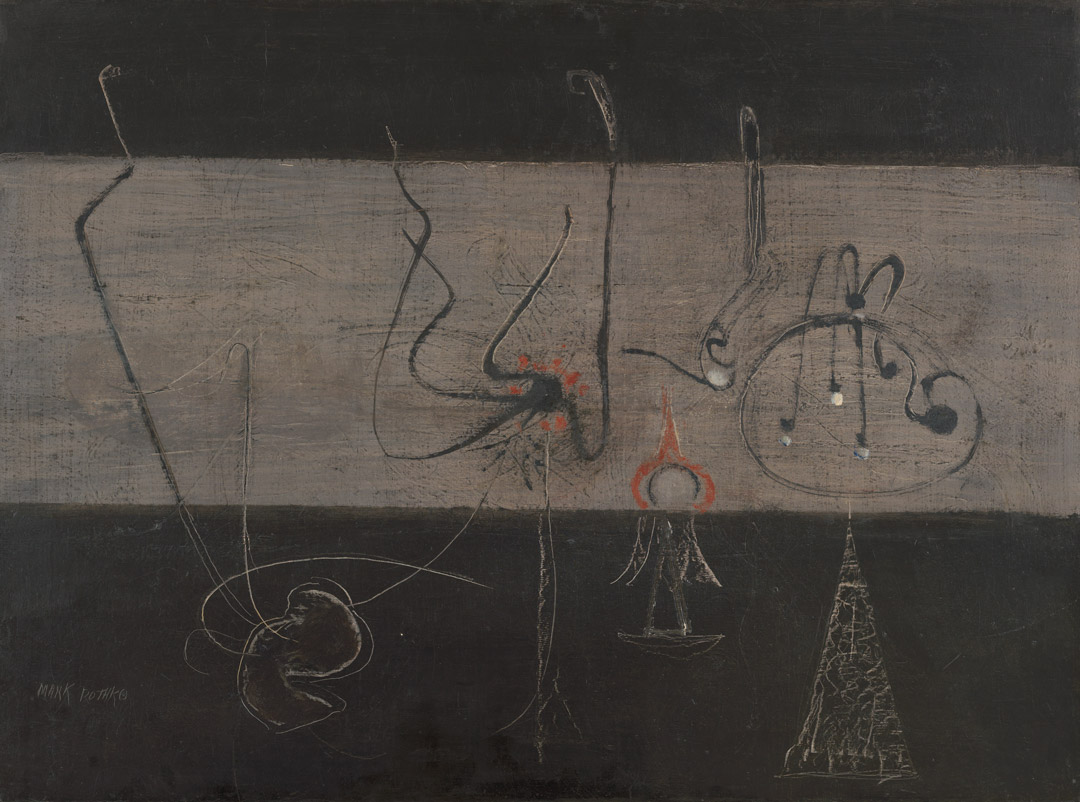

Night Watch

1960

Lee Krasner

American (1908–1984), oil on canvas, 70 x 99 in., Gift of the Friday Foundation in honor of Richard E. Lang and Jane Lang Davis, 2020.14.4, ©️ 2021 The Pollock-Krasner Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Night Watch

Eleanor Nairne

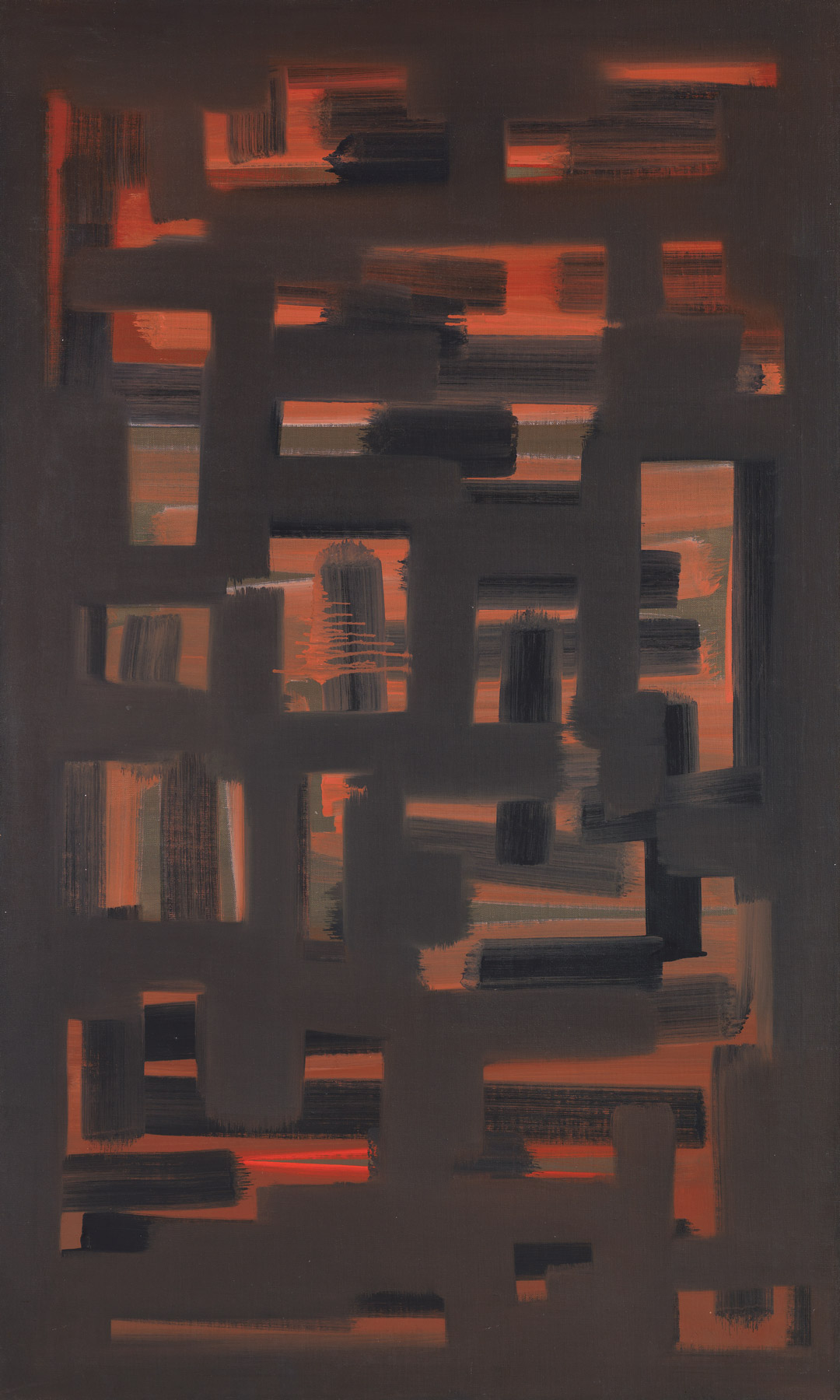

In December 1978, the poet and critic Richard Howard interviewed the artist Lee Krasner (fig. 1).1 She had just turned 70 and was a notoriously prickly character; “Oh yes, yes, I was irascible,” she had confessed to Barbara Rose a few years earlier.2 Her spikes were surely necessary, given the machismo of the postwar American art world, in which she and so many others were lumbered with the loathed qualifier of woman artist.3 But Howard was a dear friend who had summered with Krasner in Long Island, so their tone was warm, intimate. The Pace Gallery in Manhattan had organized the conversation to coincide with an exhibition of work that she had made some twenty years earlier. Back then, she had been suffering from terrible insomnia—or so the story goes.4 Working almost exclusively at night (and believing it sacrilegious to use color under artificial light), she had restricted her palette to earthy tones: raw umber, burnt sienna, ash gray, and creamy white. Which is why these formidable paintings came to be known, somewhat unfortunately, as the Umber Series. The Pace Gallery elided the problem with the restrained, if equally drab, exhibition title Paintings, 1959–1962. Howard liked to call them her “Night Journeys,” as I do too.5

How could their exchange begin anywhere but the dramatic circumstances of the paintings’ making? These were the early years after the fateful summer of 1956, when Krasner had been in Paris, on her first foray to Europe, and the critic Clement Greenberg had telephoned with grave news. Krasner’s husband, Jackson Pollock, had crashed his Oldsmobile convertible, killing himself and Edith Metzger, a friend of his lover, Ruth Kligman, who had been injured but survived.6 On August 12, the front cover of the New York Times reported: “8 Killed in 2 L.I. Auto Crashes; Jackson Pollock among Victims.”7 Krasner flew home immediately to make arrangements for the funeral. “Did the paintings represent for you not only a descent into a new crucible of emotions,” Howard ventured, “but also a specific registration of grief? Were these not mourning paintings?”8 Sometime in 1957, Krasner decided to make Pollock’s much-mythologized barn into a studio space of her own. Then loss compounded loss: her mother died in 1959, and a furious row with Greenberg led to the canceling of her exhibition at French & Company after he expressed disdain at the direction of her new work. The muted colors and sheer violence of the mark making in the Night Journeys seem to roil directly from the tumult of this time.

Krasner answered Howard cautiously: “It’s hard for me to put my finger on it in those terms.”9 Although she worked in cycles, she had always been a committed colorphile. Henri Matisse was an artistic hero precisely for the sorcery that he could enact with hot oranges and lush greens, with their fragrance of North Africa and the Pacific Islands. Although she had periods of abstinence, such as the dreaded “gray slabs” of the early 1940s, she was known and admired as a colorist. Howard called her work “chromatic fantasies”; look at the scintillating flecks of cobalt in a Little Image painting like Shellflower (1947, fig. 2) or the dense flanks of crimson in a Collage Painting like Desert Moon (1955) and you soon see why.10 The Night Journeys denied their viewer any such sensuous pleasure. As a critic at the time quipped about Night Watch (1960): “Let’s face it, brown and cream don’t make a giddy color combination.”11 It is said that depression can deplete a person’s capacity to register color; as if a tint of rose could simply drain from one’s lenses. Krasner articulated her withdrawal matter-of-factly: “I realized that if I was going to work at night I would have to knock out color altogether, because I couldn’t deal with color except in daylight.”12 Which could be seen as another way of saying the same thing.

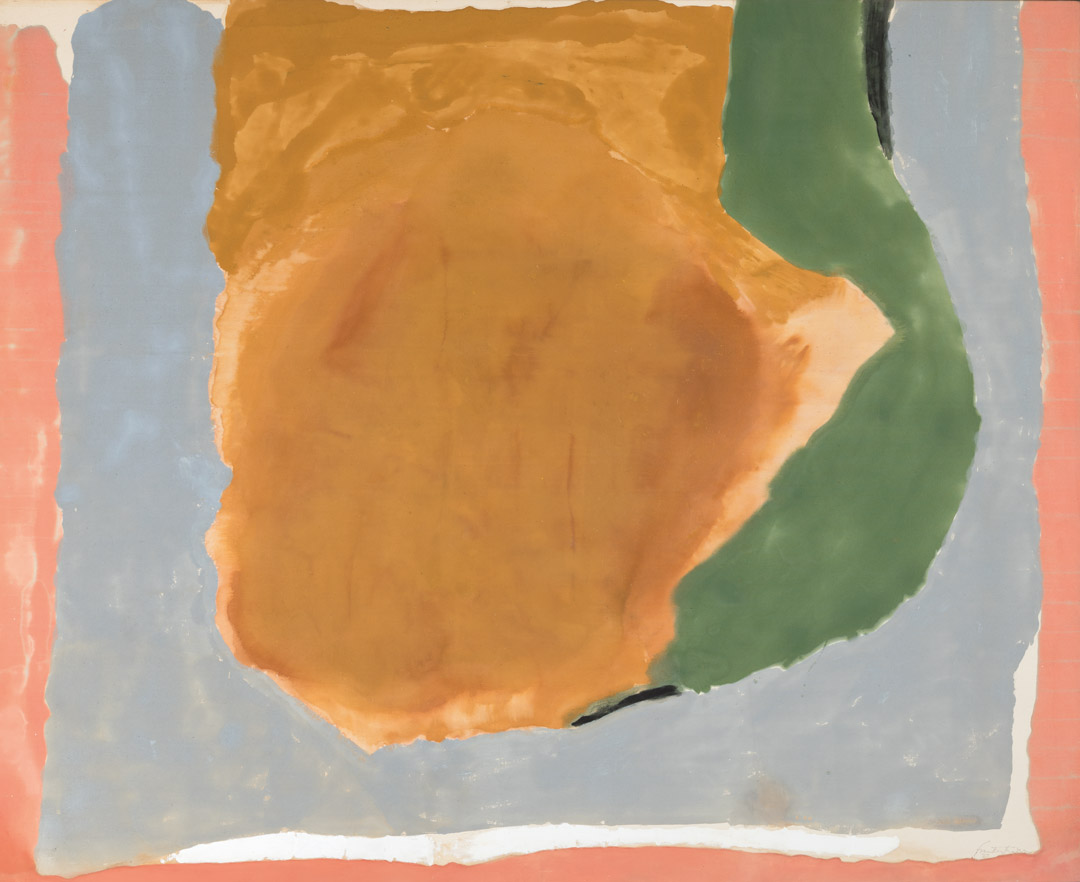

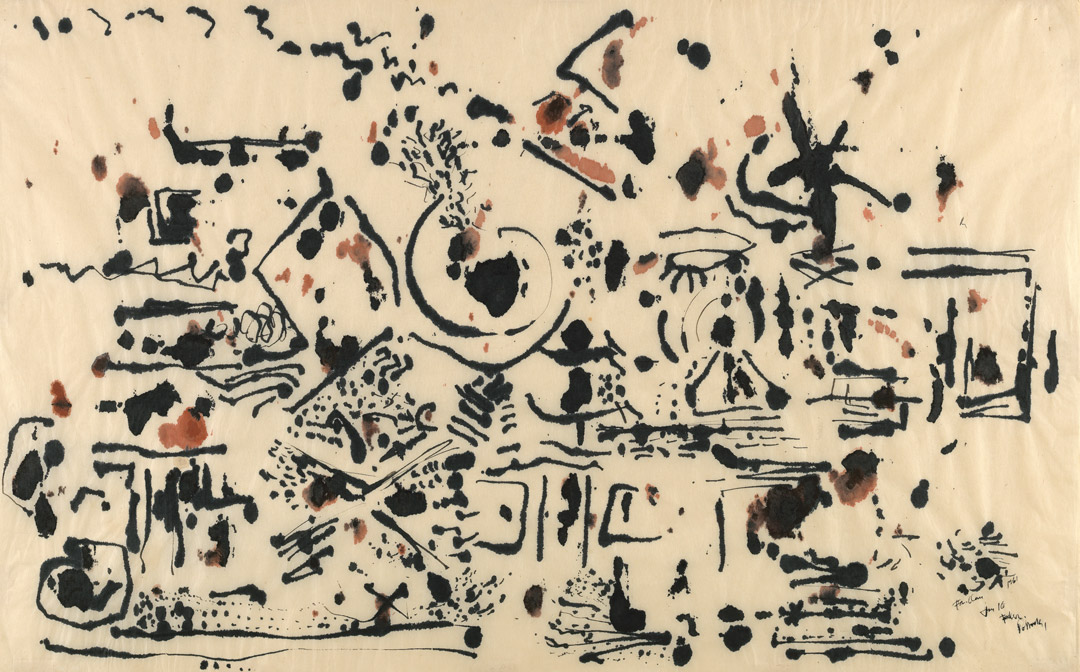

Not being able to cope with color was certainly new: the Earth Green paintings shown at Martha Jackson Gallery in February–March 1958 were some of Krasner’s brightest and most lyrical to date.13 But then, appearances can be deceiving: “I can remember that when I was painting Listen which is so highly keyed in color . . . I almost didn’t see it, because tears were literally pouring down” (fig. 3).14 This wateriness is in the work too, as Krasner stained the canvas with thinned-down paint, creating a sense of tributaries overflowing with feeling. Afterward, she thought Listen looked peculiarly like “such a happy painting,” a disparity that she explained as a kind of emotional jet lag: “The time sequence between what one feels and what is happening is not simultaneous.”15 In the popular modeling of grief by Elisabeth Kübler-Ross (first published in 1969 in On Death and Dying), denial comes first—accompanied by feelings of shock, confusion, and elation—before anger, depression, and bargaining bring a person into a state of acceptance.16 In this light, the vividness of the Earth Green works might be seen to reflect ecstatic denial. Or, indeed, release; Krasner spoke of life with Pollock as like catching “a comet by the tail,”17 and there must have been some relief (albeit conflicted) in letting go of a flying celestial object.

The Night Journeys that followed were seen by Krasner to be a path leading beneath, rather than beyond, where she had been: “Let me say that when I painted a good part of these things, I was going down deep into something which wasn’t easy or pleasant,” she told Howard.18 In this respect, her subdued palette might be read as relating to the subtle tones of the geological strata of rock or the organic pigments of prehistoric cave paintings—both frequent metaphors for the layers of the psyche. When Krasner spoke to Howard of “descending once more, bringing forth from the unconscious,” her phrasing suggests the influence of Carl Jung and his “collective unconscious”—the theory that certain primordial or archetypal images swim in an inherited part of the brain common to all of humankind.19 She had read Jung’s Integration of Personality in the summer of 1940 and found it “marvelous, you know, that he speaks in my language,” and her home library in Springs, New York, also contained a copy of Essays on a Science of Mythology (1949), coauthored by Jung with Carl Kerenyi.20 From 1939 to 1940, Pollock had been a patient of the Jungian Joseph Henderson, and Krasner was in therapy for much of the 1950s with a controversial Sullivanian, Leonard Siegel, whom she described as working in “the direction of Freud.”21

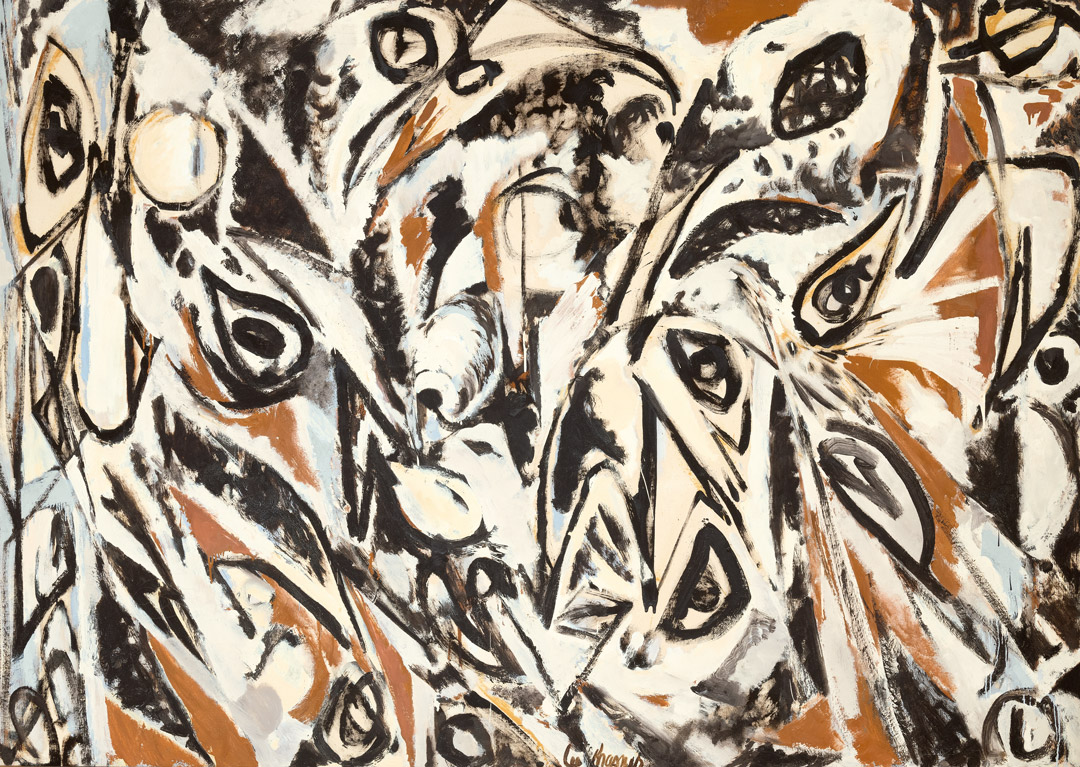

Of all the Night Journeys, Night Watch feels perhaps the most loaded with psychic content. The painting borrows its title from the popular name for Rembrandt’s Militia Company of District II under the Command of Captain Frans Banning Cocq (1642, Rijksmuseum)—a work famed for its epic pageantry and dramatic use of light and dark. The title brings to mind the apprehension induced by the very need for nocturnal policing: act 1, scene 1 of Hamlet, for instance, in which the guards anxiously “watch the minutes of this night” in haunted Elsinore.22 The canvas is covered in a whorl of thick arcs of somber paint, from which a number of eyes seem to peer out menacingly. In dropping the definite article from Rembrandt’s title, Krasner unleashes the question of who is watching whom. Oracular imagery also features in other works in the series, such as The Eye Is the First Circle (1960, Glenstone Museum), named after the first line of the 1841 essay “Circles” by Ralph Waldo Emerson, and Vigil (1960, Private Collection), which Krasner described to Howard as having “to do with being on guard at every moment while one is descending.”23 To where, you might ask? The homonym of “eye” and “I” suggests a journey within subjectivity and could be a direct allusion to Jung, whose statements on this link include: “My consciousness is like an eye that penetrates to the most distant spaces.”24

At the time, many artists and writers working internationally wanted to plumb the depths of interior life. During the war, André Breton and fellow Surrealists seeking refuge in New York had brought with them techniques like automatism as a pathway to the unconscious, as well as a predilection for mythic origin stories and a revival of primitivism. In 1937, the writer and artist John Graham published “Primitive Art and Picasso,” an article that Krasner likely read, given that she much admired Graham’s System and Dialectics of Art, published the same year.25 In 1943, fellow Abstract Expressionists Mark Rothko and Adolph Gottlieb wrote a letter to Edward Alden Jewel, art critic of the New York Times, explaining that “to us art is an adventure into an unknown world, which can be explored only by those willing to take the risks. . . . That is why we profess spiritual kinship with primitive and archaic art.”26 There would be countless other statements of this kind by those who gathered at the Cedar Tavern, which might be best summarized by Pollock’s infamous declaration that he did not need to rework images of nature, since “I am nature”—itself a brilliant reworking of Paul Cézanne’s earlier statement that “nature is on the inside.”27

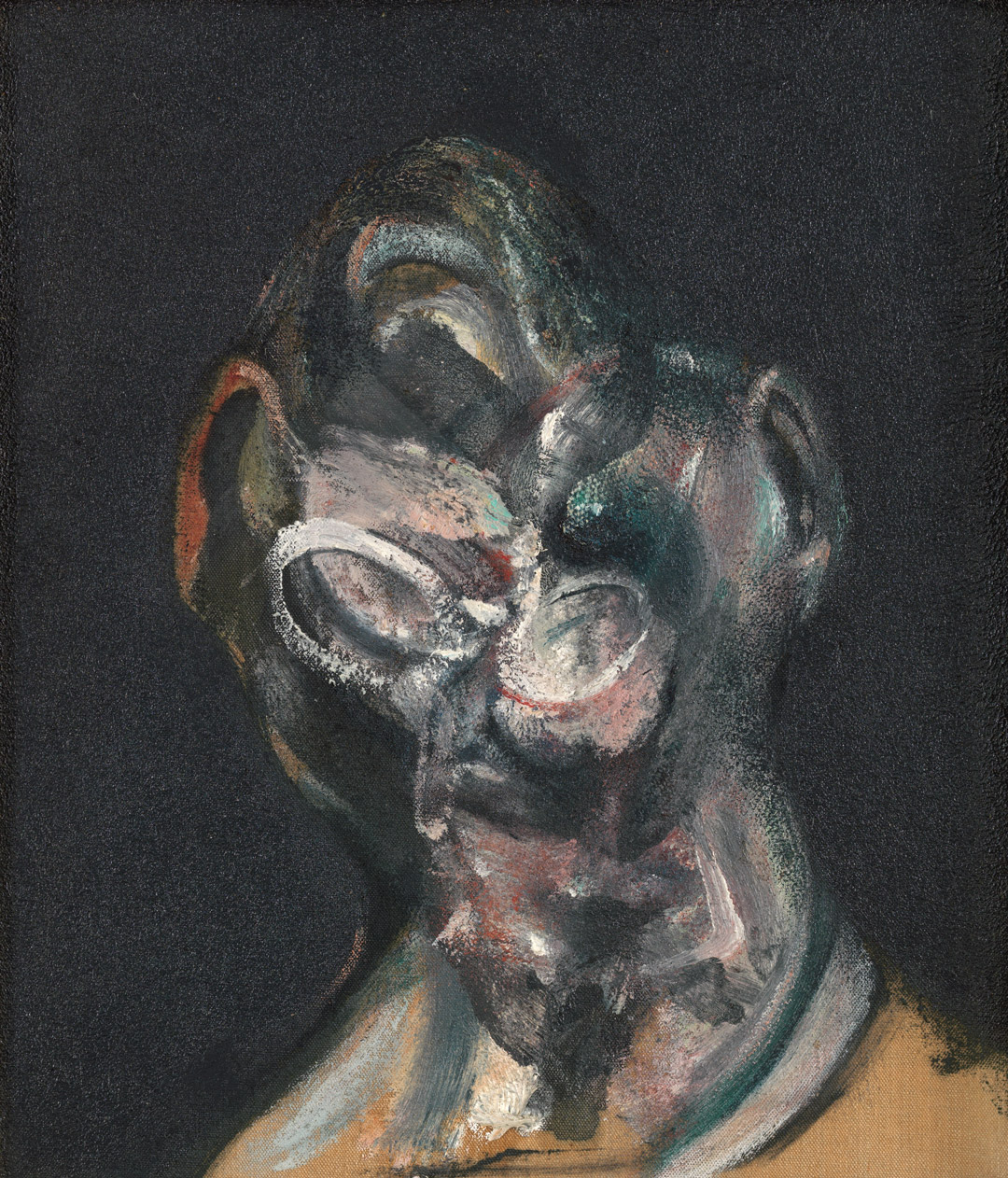

For Michael Leja, these are prime examples of what he describes as “Modern Man discourse,” which was very much in the air in postwar New York.28 In 1959, the year that Krasner embarked on her Night Journeys, Miles Davis released Kind of Blue, his pioneering experiment in improvisatory modal jazz, and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum opened to the public, designed by Frank Lloyd Wright as a conscious inversion of the stepped pyramids of Mesopotamia and invoking the biomorphic forms marveled at by Darcy Wentworth Thompson in his influential study On Growth and Form (1917). This was also the year that Peter Selz curated New Images of Man at the Museum of Modern Art, featuring the work of twenty-two men, including Francis Bacon, Willem de Kooning, Jean Dubuffet, Alberto Giacometti, Leon Golub, and Pollock, alongside that of one woman—Germaine Richier (fig. 4). In the introduction to the catalogue (a copy of which is also in the library in Springs), Selz writes:

The imagery of man which has evolved from [mid-twentieth-century life] reveals sometimes a new dignity, sometimes despair, but always the uniqueness of man as he confronts his fate. Like Kierkegaard, Heidegger, Camus, these artists are aware of anguish and dread, of life in which man—precarious and vulnerable—confronts the precipice, is aware of dying as well as living.29

Being a woman made Krasner no less susceptible to the dominance of Modern Man ideology, which is powerfully at play in her Night Journeys—paintings wrought of an awareness of an existential precipice. The critics of the day on both sides of the Atlantic appraised her work within this framework too. In an article for Arts Review coinciding with her exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery in 1965, Kenneth Coutts-Smith wrote that her “images are not so much created but released from the very deep levels of the imagination.”30 When we look at them today, we might be struck by the confluence of these different forces: the dramatic impact of personal grief and the need to be pragmatic through a period of desperate sleeplessness; the artistic impulse to break into a new cycle of imagery; the working through of collective trauma, including the Second World War and the intensification of Cold War politics; and the urgency felt transnationally to drill down into what had made humankind capable of such atrocities. As the painter Amy Sillman recently articulated: “That psychic landscape of trying to produce new knowledge, new subjectivity, new insight, new form—that’s the mandate of that kind of painter. And that is such a burden.”31 Yet with the Night Journeys, Krasner found a way to whip that weight into a state of electric grace, watched over by eyes looking within and without the edges of the canvas—into its maker and onto its viewer, with alarming perspicacity.

Author

Eleanor Nairne is a writer and curator based at the Barbican Art Gallery in London, where her recent exhibitions include Jean Dubuffet: Brutal Beauty (catalogue published by Prestel, 2021), Lee Krasner: Living Colour (Thames and Hudson, 2019), and Basquiat: Boom for Real (Prestel, 2017). She has contributed essays and criticism to publications including frieze, the London Review of Books, and the New York Times.

Notes

1 Richard Howard, “A Conversation with Lee Krasner,” 1978, in Lee Krasner: Paintings 1959–1962 (New York: Pace Gallery, 1979), n.p.

2 Lee Krasner, interview by Barbara Rose, ca. 1975, box 10, C77, Barbara Rose Papers, 930100, Getty Research Institute.

3 Krasner had many artist contemporaries who were women, including Mary Abbott, Perle Fine, Louise Nevelson, Anne Ryan, Janet Sobel, and Hedda Sterne, as well as the famous four covered in Mary Gabriel’s gripping Ninth Street Women: Lee Krasner, Elaine de Kooning, Grace Hartigan, Joan Mitchell, and Helen Frankenthaler—Five Painters and the Movement that Changed Modern Art (Boston: Little, Brown, 2018).

4 We must, of course, treat artists’ stories with a degree of caution; Krasner, for instance, liked to tell and retell the same anecdotes until they were as ossified as stone. What is useful here is to consider how it served her to tell the story in this way.

5 In his conversation with Krasner, Howard said that “there is a category of experience that in Hebrew mythology is in fact called a night journey, a descent down into the darkness—and it seems to me that you . . . are working in this mode here.” Howard, “Conversation,” n.p. Krasner was raised in an Orthodox Jewish Russian émigré home in Brooklyn, which may have strengthened the connection to Hebrew myth for Howard.

6 For more on this period, see Gail Levin, Lee Krasner: A Biography (London: Thames and Hudson, 2020), 350–60.

7 Cover, New York Times, August 12, 1956.

8 Howard, “Conversation,” n.p.

9 Krasner, in Howard, “Conversation,” n.p.

10 Howard, “Conversation,” n.p.

11 Vivien Raynor, “Lee Krasner” [Wise Gallery], Arts Magazine 35 (January 1961): 54.

12 Krasner, in Howard, “Conversation,” n.p.

13 Lee Krasner: Recent Paintings, Martha Jackson Gallery, New York, February–March 1958, featured seventeen works, including Listen, Earth Green, Spring Beat, Upstream, and The Seasons.

14 Krasner, in Howard, “Conversation,” n.p.

15 Krasner, in Howard, “Conversation,” n.p.

16 Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, On Death and Dying (New York: Macmillan, 1969).

17 Lee Krasner, quoted in Geoff Dyer, ed., John Berger: Selected Essays (London: Bloomsbury, 2001), n.p.

18 Krasner, in Howard, “Conversation,” n.p.

19 Carl Jung, “The Concept of the Collective Unconscious,” accessed July 13, 2020, http://www.bahaistudies.net/asma/The-Concept-of-the-Collective-Unconscious.pdf.

20 Levin, Lee Krasner, 147. My thanks to Helen Harrison of the Pollock-Krasner House and Study Center for allowing me to visit the house and explore the library—as well as the record collection.

21 Levin, Lee Krasner, 297.

22 William Shakespeare, Hamlet, 1599–1601, ed. Harold Jenkins (London: Arden, 1982), 1.1.30.

23 Krasner, in Howard, “Conversation,” n.p.

24 Herbert Read, Michael Fordham, and Gerhard Adler, eds., C. G. Jung: The Collected Works (London: Routledge, 1973), 1,482.

25 John Graham, “Primitive Art and Picasso,” Magazine of Art 30, no. 4 (April 1937): 236–39; and John Graham, System and Dialectics of Art (New York: Delphic Studios, 1937).

26 Mark Rothko and Adolph Gottlieb, “Rothko and Gottlieb’s Letter to the Editor, 1943,” in Writings on Art: Mark Rothko, ed. Miguel López-Remiro (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2006), 36.

27 Jackson Pollock made this remark in 1942 after being introduced by Krasner to her teacher Hans Hofmann, who warned of the risks of repeating yourself if you did not work from nature. See Paul Crowther and Isabel Wünsche, eds., Meanings of Abstract Art: Between Nature and Theory (New York: Routledge, 2012). For more on Cézanne’s relationship to nature, see Joyce Medina, Cézanne and Modernism: The Poetics of Painting (New York: State University of New York Press, 1995), 97.

28 Michael Leja, Reframing Abstract Expressionism: Subjectivity and Painting in the 1940s (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1993).

29 Peter Selz, New Images of Man (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1959), 11.

30 Kenneth Coutts-Smith, “An Interview with Lee Krasner,” Arts Review, October 2, 1965, republished August 20, 2019, http://artreview.com/archive-2-october-1962-feature-lee-krasner/.

31 Amy Sillman, in conversation with Helen Molesworth, on “Lee Krasner: Deal with It,” Recording Artists: A Podcast from the Getty, Season 1: Radical Women, accessed 8 July 2020, http://www.getty.edu/recordingartists/season-1/krasner/.

Explore the Collection

Sort by Chronology

Sort by Artist

Sort by Author

Franz Kline, Painting No. 11, 1951

Acquired November 13, 1970

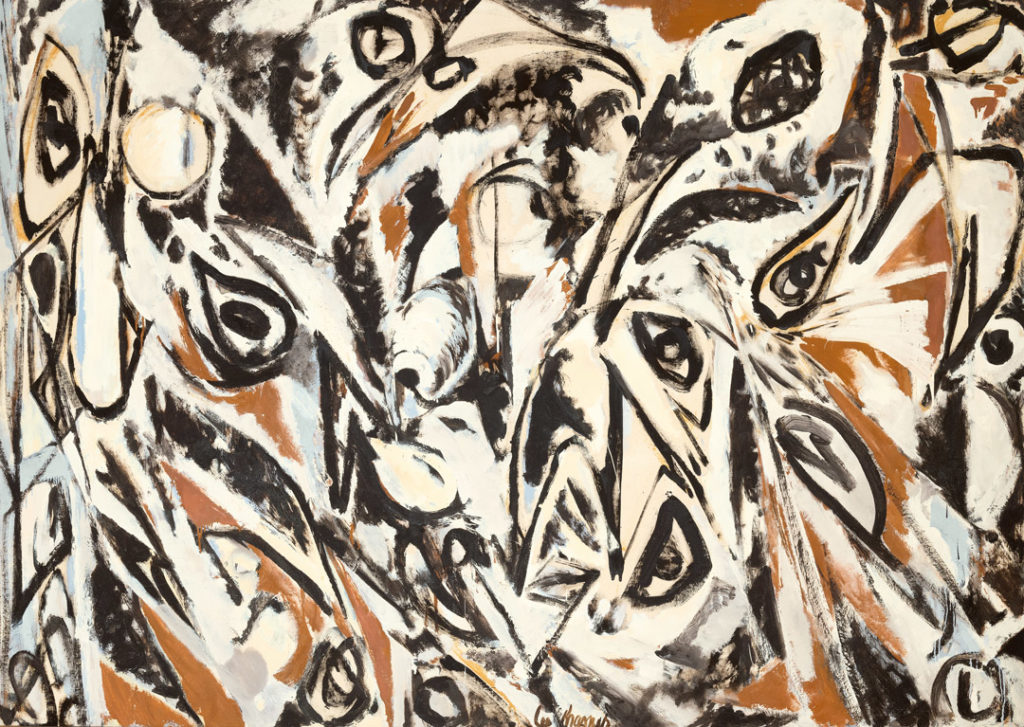

Mark Rothko, Untitled, 1963

Acquired May 18, 1972

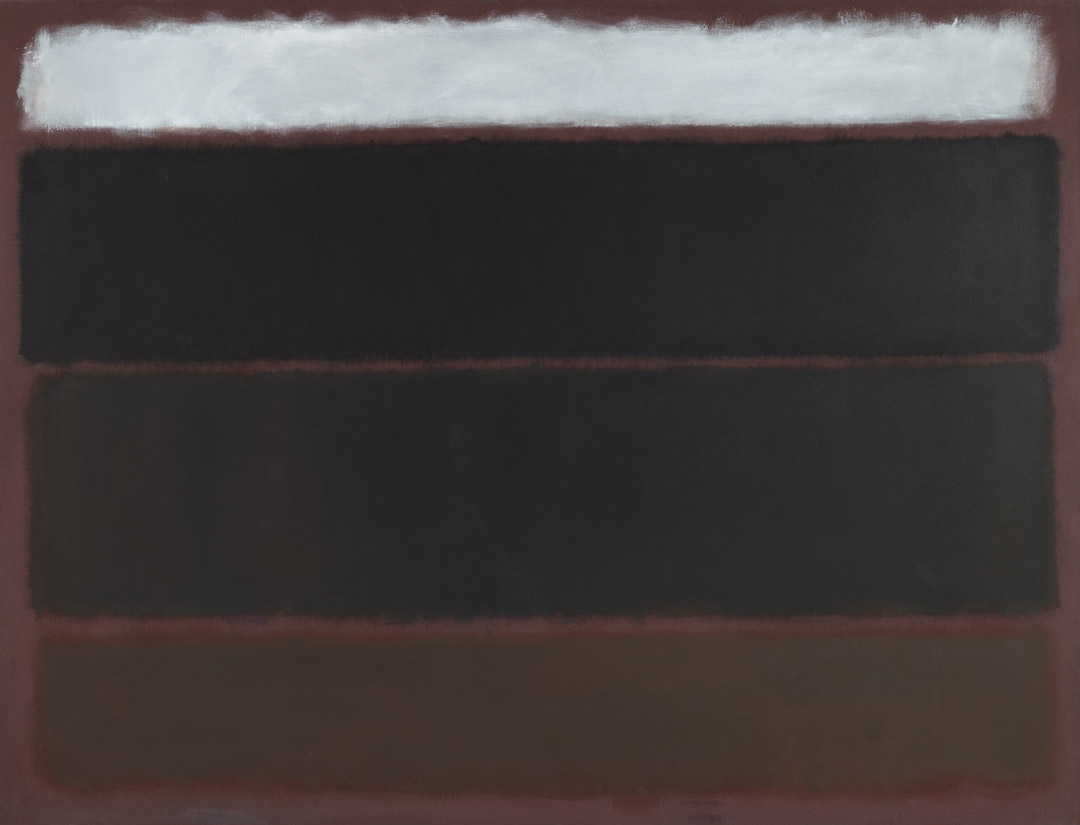

Robert Motherwell, Before the Day, 1972

Acquired October 12, 1972

Adolph Gottlieb, Crimson Spinning #2, 1959

Acquired December 11, 1972

Helen Frankenthaler, Dawn Shapes, 1967

Acquired April 26, 1973

Clyfford Still, PH-338, 1949

Acquired November 10, 1973

Ad Reinhardt, Painting, 1950, 1950

Acquired January 8, 1974

Jackson Pollock, Untitled, 1951

Acquired March 29, 1974

Francis Bacon, Portrait of Man with Glasses I, 1963

Acquired October 24, 1974

Alberto Giacometti, Femme de Venise II, 1956

Acquired January 2, 1975

Robert Motherwell, Irish Elegy, 1965

Acquired November 7, 1975

Francis Bacon, Study for a Portrait, 1967

Acquired November 20, 1976

Willem de Kooning, Town Square, 1948

Acquired December 6, 1976

Joan Mitchell, The Sink, 1956

Acquired September 12, 1977

David Smith, Cubi XXV, 1965

Acquired February 22, 1978

Philip Guston, To B.W.T., 1952

Acquired February 14, 1979

Mark Rothko, Untitled, ca.1945

Acquired November 12, 1980

Lee Krasner, Night Watch, 1960

Acquired November 19, 1981

Philip Guston, The Painter, 1976

Acquired February 1, 1982