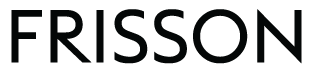

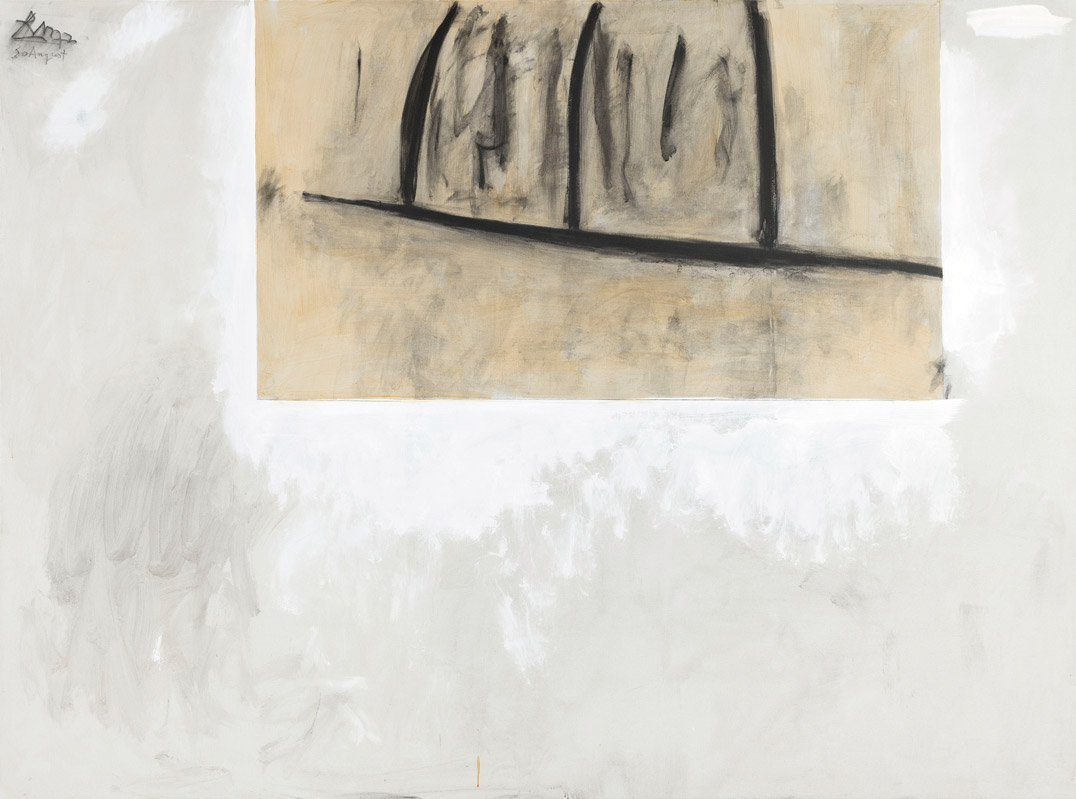

The Painter

1976

Philip Guston

American, born Canada (1913–1980), oil on canvas, 74 x 116 in., Gift of the Friday Foundation in honor Richard E. Lang and Jane Lang Davis, 2020.14.11, photo: Spike Mafford/ Zocalo Studios. Courtesy of the Friday Foundation. © The Estate of Philip Guston, courtesy Hauser & Wirth.

The Painter

Robert Storr

Although he lacked the reputation for stall-kicking brashness that Pollock earned early on, and despite the fact that he had a command of traditional skills that Pollock for the most part lacked, Philip Guston was among the great risk takers of his generation of American artists. Contrary to the logic that living free is easy if you’ve got nothing left to lose, by 1950, when Guston had just reached his early forties and put everything on the line to explore a radical abstraction, he had a great deal to lose. By 1966, when he again bet the farm on what seemed an abrupt about-face, he had still more at risk.

In large part, this was because on the second occasion he was not neatly swinging back to “figuration,” pendulum style, a phenomenon that might simply have perplexed and dismayed some of his avant-garde supporters while pleasing his more conservative enthusiasts of years past. Rather, he appeared to have veered wide of any aesthetically comprehensible formal dialectic inasmuch as his new “cartoon”-derived work struck many as wholly out of character with any of his previously known artistic identities, while, in the view of others, veering perilously close to the vulgar commercial imagery favored by Pop painters half his age.

In truth, though, Guston was reconnecting to his earliest mentors: comic strip masters such as the African American creator of the nationally syndicated Krazy Kat, George Herriman, whose work Guston had copied from the papers as a boy.1 It was Herriman and his colleagues in the “funny pages” who pioneered the uniquely antic graphic idiom subsequently latched onto by Robert Crumb, Art Spiegelman, and others who led the “Comix” revival of the 1960s. More than a few critics assumed that Guston was aping them rather than mining a rich, deep but long-neglected seam in his own imagination.

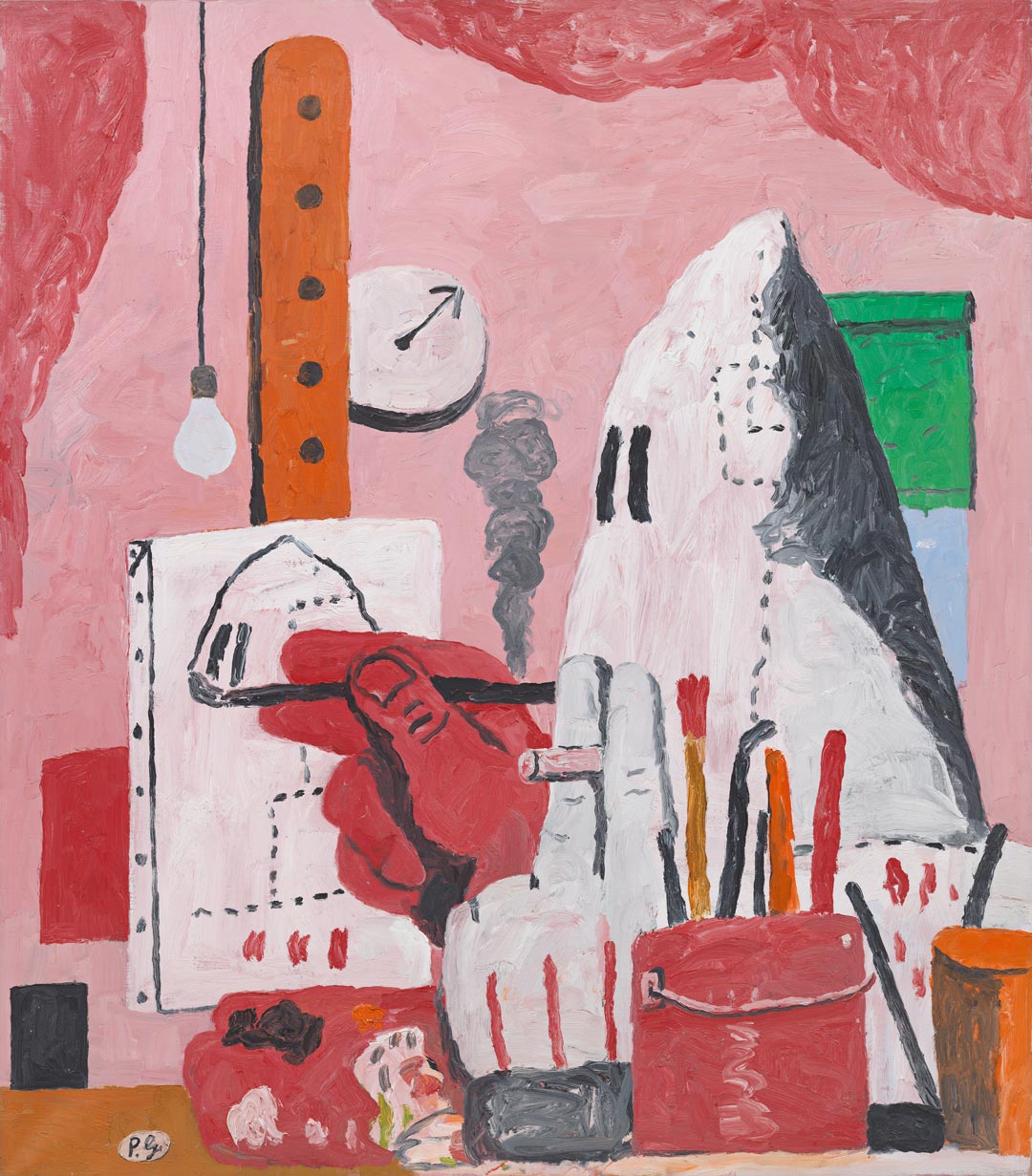

But he was—although, in keeping with his profoundly unsettled nature and ambivalent sensibility, he refused to deploy the tropes of cartooning “just for laughs.” Instead, he used them to address the most wrenching aspects of contemporary American life and of his personal reality. In that spirit, he began his last creative period delineating deliberately heavy-handed still lifes of the tools of his painterly trade found in his studio. He was also commenting in jarringly slapstick manner on the violence in American streets outside that safe haven—violence that heralded and ran through the presidency of Richard Nixon, to whom he devoted an astonishing series of caricatures, which constitute his only foray into cartooning for its own sake in the public sphere.

Most notable of his frankly—yet anything but one-dimensionally or programmatically partisan—political works were those in which Guston reprised the iconography of his radical anti-lynching tableaux of the 1930s featuring hooded members of the Ku Klux Klan. When Klansmen returned in the 1970s, they came across as a crew of bumbling “hooded” thugs or variations on the Keystone Kops emanating from the dark side. Guston’s purpose was not to make light of these still-dangerous marauders—far from it. He had, in part, been prompted to revisit them by the resurgence of the Klan during the civil rights movement and by the murderous role it had played in the 1963 bombing of Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, causing the deaths of four Black girls attending Sunday services.

To that extent, fear, loathing, and outrage are at the core of all of Guston’s late Klan imagery. In this context, the cartooning style he had adopted might seem to be at odds with the depth and seriousness of the artist’s convictions, but indicates that something else is at issue as well. Namely, these works mark an uneasy effort to bear witness to the horrors the Klan perpetrated, and to their demonic stupidity, from inside rather than from outside their cohort. Guston’s point of view constitutes an ethically courageous admission that “we” are more like “them” than most of “us” would like to believe, that the Klansmen’s weaknesses, prejudices, brutality, and cowardice are also an ineradicable part of “our” human nature. In their sheer absurdity—which is where the ridiculous element of these lampoons comes into play—they remind us that the ultimate common denominator of our human condition is rooted in our schizophrenia, our split personalities, and our capacity for inflicting pain and suffering, as well as in being good, our dignity and abjection, and our probably tragicomic fates.

In the highly polarized 1960s and 1970s, such extreme, self-revealing masquerades were exceedingly rare in a sharply divided, which-side-are-you-on nation. Now, perhaps, people have a keener appreciation of how hard it can be to tell the good guys from the very bad guys or, for that matter, to be absolutely sure on which side of that line one is standing. For Guston, who had long been guarded about his heritage, crucial insight into the anomalies of ethnic and racial identity had been provided by the Russian Jewish writer Isaac Babel. As an official Soviet journalist, Babel rode with and reported on his own hereditary enemies, the Cossacks, who made up much of the Red Cavalry fending off the counterrevolutionary White armies but who, in the not-so-distant-past, had terrorized the Jewish communities of the shtetl.

Being and doing evil thus became the subtext for the Klan pictures. In these images, Guston broke ranks with those who were all too quick to absolve whites from the harm done to Black people in this country on the assumption that only obvious, night-riding villains hidden under white sheets were to blame for systemic racism in the United States.

Guston knew better. Accordingly, he painted artists in hoods at their easels limning self-portraits (fig. 1). It was a bold, brave decision whose ramifications reach into the twenty-first century. When art is judged to be before its time, it usually implies that the work bears the traces of stylistic precocity, of being in advance of a raft of work with which it shares obvious formal traits. But art can also be ahead of its time in thematic ways as well. As recent events have proved, we as a nation remain far from dispelling the shadow that the heritage of racism has cast over us all—a heritage that Guston symbolically acknowledged in his choice of hooded “protagonists.”

Despite this prescience, fundamental misunderstandings of Guston’s intentions in overtly political works of the 1930s as well as of his concerns in the late 1960s and early 1970s led to a woefully misguided delay in the tour of an international retrospective of his career in 2020.2 In short, art “discourse” and public appreciation of the tenacity of racist attitudes in the United States inspired a basic misreading of his Klan imagery, rendering them temporarily taboo. That taboo, and the debate it triggered over the decision to postpone the Guston exhibition, coming as it did in the waning days of President Donald Trump’s administration, oddly served to assist in correcting overdetermined interpretations of his work. This, in turn, prompted an overdue rethinking of deep-seated biases in contemporary art discourse—not least the canard that Abstract Expressionism signaled a widespread retreat from politics among artists. To whatever degree that shift applies to other members of Guston’s New York School cohort, his own later work doubled back on the commitments of his politically radical years and cast them in a fresh and disabused but, for all that, still more passionate light.

That light was dark if not explicitly nocturnal. And it became more so while the 1970s wore on—and wore him down—even as Guston’s self-questioning cut ever closer to the bone. With his own studio as the main stage of the psychological, social, and philosophical dramas that he played out in blunt but always spontaneously speculative strokes, the costuming, decor, and supporting cast changed and evolved. By mid-decade, Klansmen had all but vanished from his work, and their intrusive menace—the riotous world invading the inner sanctum of his artistic vocation—was replaced by that of densely massed, stamping feet in hobnailed boots and shoes.

Thus, if in The Studio (1969) we have a depiction of “the artist” as a hooded brute explicitly erasing the division between “them” and “us” referred to above, and if in Bad Habits (1970, fig. 77) we have similar Klan figures interspersed with gigantic liquor bottles effectively equating solitary drinking with the lonely, hallucinatory intoxication of painting, in The Painter (1976) the comic exaggeration is gone, and we are presented with a stripped-down version of the artist’s plight. Cut off and sealed in by yet another iteration of the masonry wall motif Guston had deployed since the 1930s, a grizzled, balding head rises just above the tiers of bricks, its forehead furrowed and its eyes bloodshot. A cigarette-wielding hand brackets the desperate visage to one side, and to the other, an empty fifth of spirits and a tumbler are arranged atop the bricks. One is almost moved to sing, “Ninety-nine bottles of Scotch on the wall . . .”

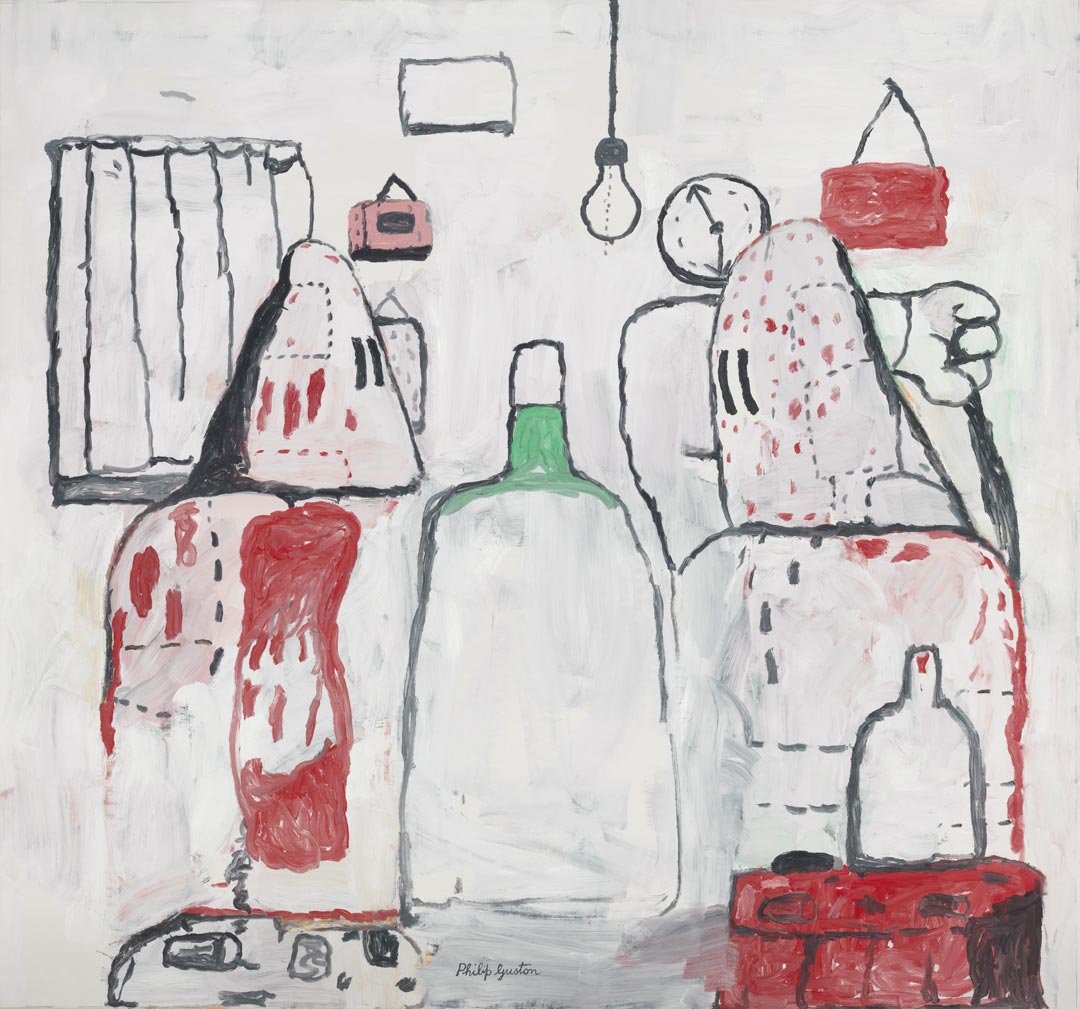

To be sure, hard drinking is part of the macho myth of Abstract Expressionism, but directly or indirectly it killed or contributed to the premature deaths of many of that tendency’s leading exponents, starting with epically, self-destructively drunk Jackson Pollock and continuing on through the suicidally alcoholic Mark Rothko, the habitually thirsty but more genteel Robert Motherwell, and the otherwise bibulous sculptors Tony Smith and David Smith, to mention only a handful of the greats. That said, on the authority of Rudolf Burckhardt, the filmmaker and photographer who took pictures of their work for Art News and various galleries, one can say that booze generally did not overtake these artists until they had begun to experience a measure of material success and to have “careers” that required hanging out with collectors who paid the bar bills, all of which ultimately added to their anxieties.

To that degree, the “critique” of Abstract Expressionism by contemporary historians and commentators by and large lacks pathos, given the details left out of current retellings by those fed up with the artists’ legend. From inside the prison constructed around him and fellow inmates confined by circumstances including fame and ill-founded hero worship, Guston portrayed his own solitary confinement and alienation in raw, unromantic, antiheroic, and essentially unforgiving terms.

Ironically, he did so at the “peak” of his artistic creativity, which he reached while in internal exile in upstate New York, far from the center of the New York City–based art world that had formerly lionized him. Of all their peers, only Guston and de Kooning fully developed and deployed a “late manner.” And, without a doubt, it was the canvases created during that final phase that have in the long run secured Guston’s pivotal place in the pantheon of internationally renowned painters of the late twentieth century’s “postmodern” era. Nevertheless, they were, in fact, the work of a perpetually anguished modern artist who, in a period governed by competing aesthetic ideologies, was never comfortable being a rule-bound modernist. Viewed from that angle, he perfectly fits the description of the type of artist that de Kooning referred to when he said, “Some painters, including myself, do not care what chair they are sitting on. They do not want to ‘sit in style.’”3 Guston was likewise too restless to sit pat, no matter what the rewards, and, as a result, drove himself hard to the very end. In 1980, he died suddenly of a heart attack. He was only 66.

Author

Robert Storr is an artist, critic, and curator based in New York. He was previously senior curator of painting and sculpture at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, and professor of painting and printmaking at Yale University School of Art. His writings on Philip Guston include Philip Guston (Abbeville, 1985) and Philip Guston: A Life Spent Painting (Laurence King, 2019).

Notes

1 Herriman’s Krazy Kat character first appeared in his strip The Dingbat Family in the New York Evening Journal, July 26, 1910. The paper published the inaugural Krazy Kat vertical daily strip on October 28, 1913. Crucially, the full-page Sunday Krazy Kat comic premiered in the paper’s arts and drama section on April 23, 1916, exposing Herriman’s work to a much broader readership than it might have had in the comics section. According to biographer Patrick McDonnell, this event sparked the strip’s wide popularity. See Patrick McDonnell, Krazy Kat: The Comic Art of George Herriman (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1986).

2 See, for example, Julia Jacobs and Jason Farago, “Delay of Philip Guston Retrospective Divides the Art World,” New York Times, September 25, 2020, http://www.nytimes.com/2020/09/25/arts/design/philip-guston-exhibition-delayed-criticism.html; Sarah Cascone, “Philip Guston’s Daughter and Other Critics Speak Out against Four Museums’ Decision to Postpone a Major Retrospective on the Artist,” ArtNet, September 25, 2020, http://news.artnet.com/exhibitions/philip-guston-retrospective-postponed-1910658; “Open Letter: On Philip Guston Now,” Brooklyn Rail, September 30, 2020, http://brooklynrail.org/projects/on-philip-guston-now/; and Murray Whyte, “What Museums Can Learn from Philip Guston and His Frank Take on ‘White Culpability,’” Boston Globe, January 6, 2021, http://www.bostonglobe.com/2021/01/06/arts/what-museums-can-learn-philip-guston-his-frank-take-white-culpability/.

3 Willem de Kooning, “What Abstract Art Means to Me,” lecture, What Is Abstract Art symposium, Museum of Modern Art, New York, February 5, 1951, http://www.dekooning.org/documentation/words/what-abstract-art-means-to-me.

Explore the Collection

Sort by Chronology

Sort by Artist

Sort by Author

Franz Kline, Painting No. 11, 1951

Acquired November 13, 1970

Mark Rothko, Untitled, 1963

Acquired May 18, 1972

Robert Motherwell, Before the Day, 1972

Acquired October 12, 1972

Adolph Gottlieb, Crimson Spinning #2, 1959

Acquired December 11, 1972

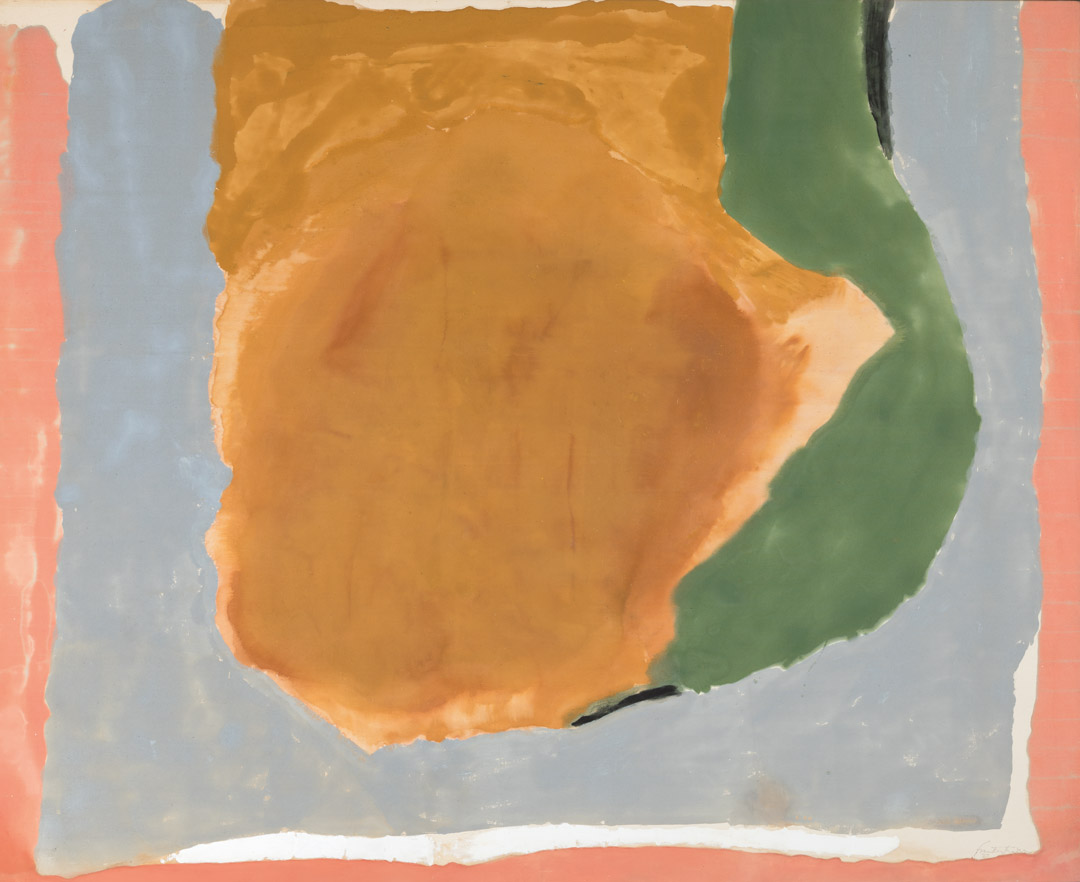

Helen Frankenthaler, Dawn Shapes, 1967

Acquired April 26, 1973

Clyfford Still, PH-338, 1949

Acquired November 10, 1973

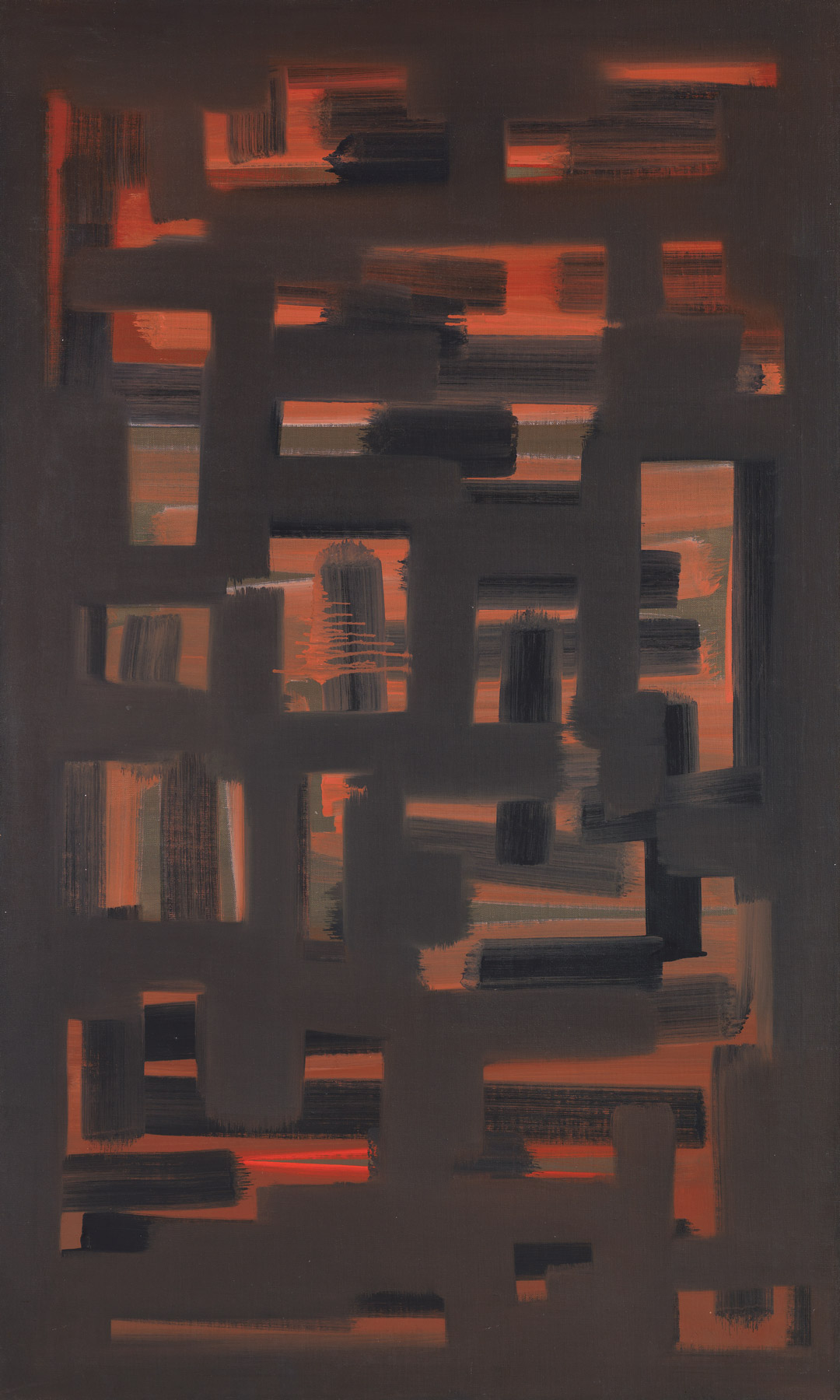

Ad Reinhardt, Painting, 1950, 1950

Acquired January 8, 1974

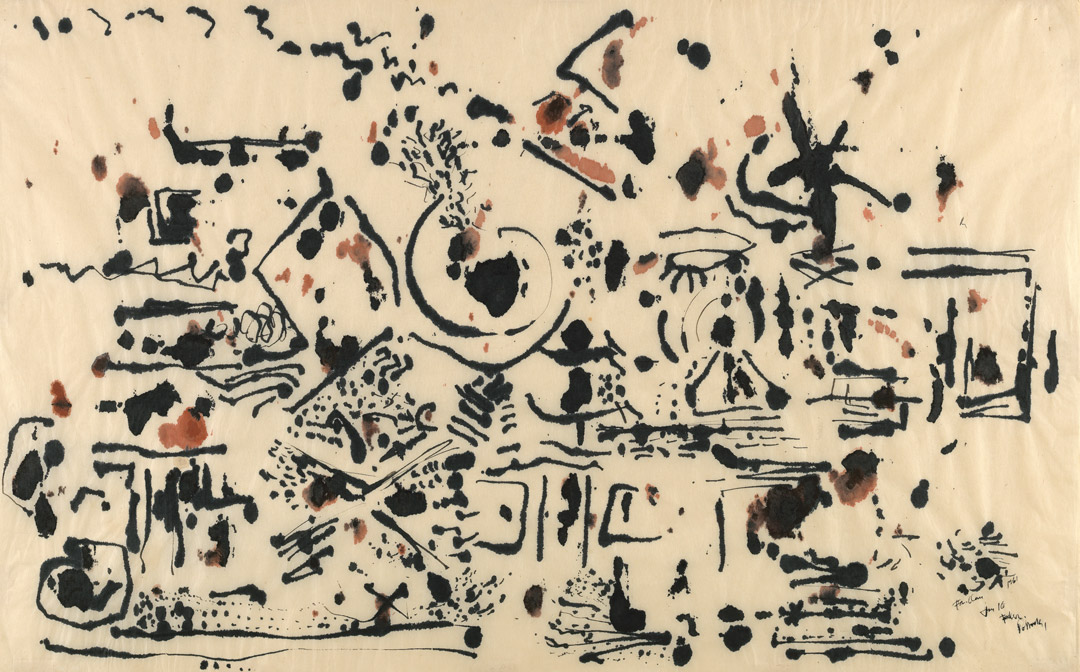

Jackson Pollock, Untitled, 1951

Acquired March 29, 1974

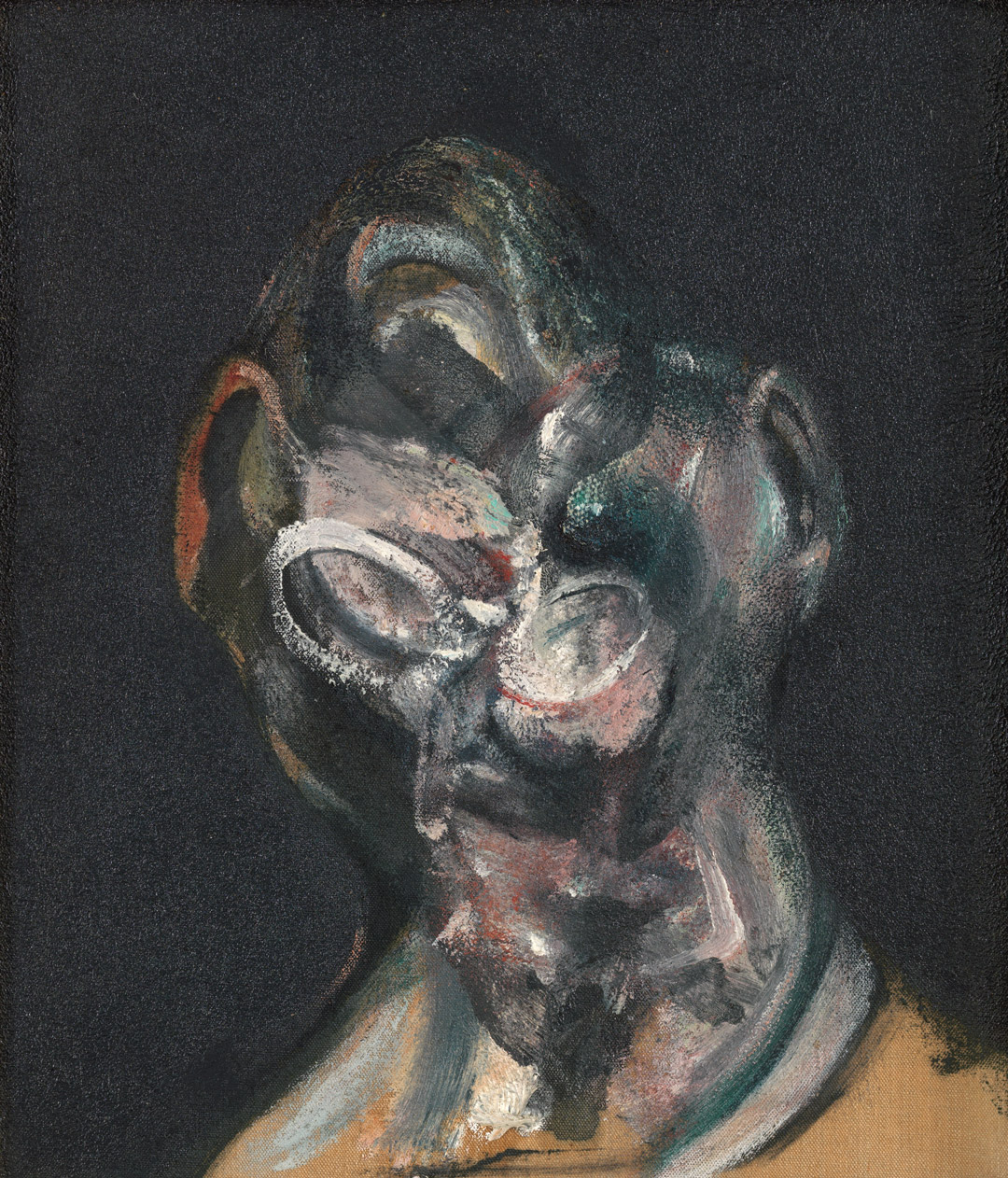

Francis Bacon, Portrait of Man with Glasses I, 1963

Acquired October 24, 1974

Alberto Giacometti, Femme de Venise II, 1956

Acquired January 2, 1975

Robert Motherwell, Irish Elegy, 1965

Acquired November 7, 1975

Francis Bacon, Study for a Portrait, 1967

Acquired November 20, 1976

Willem de Kooning, Town Square, 1948

Acquired December 6, 1976

Joan Mitchell, The Sink, 1956

Acquired September 12, 1977

David Smith, Cubi XXV, 1965

Acquired February 22, 1978

Philip Guston, To B.W.T., 1952

Acquired February 14, 1979

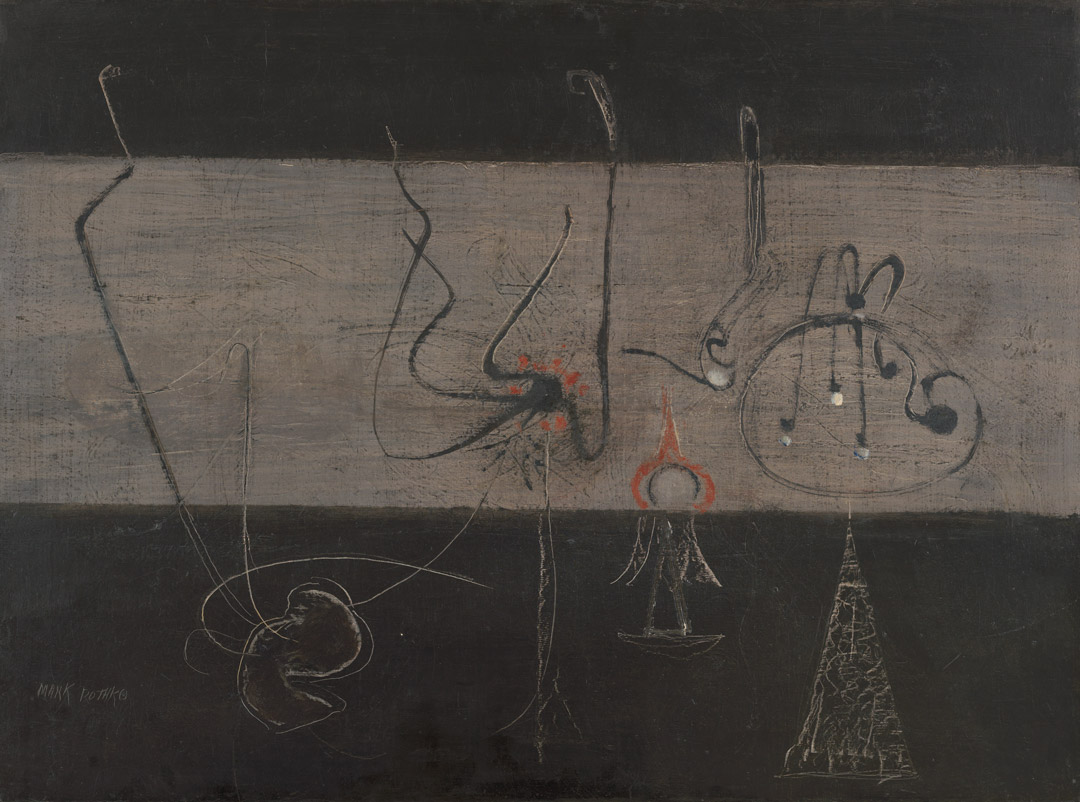

Mark Rothko, Untitled, ca.1945

Acquired November 12, 1980

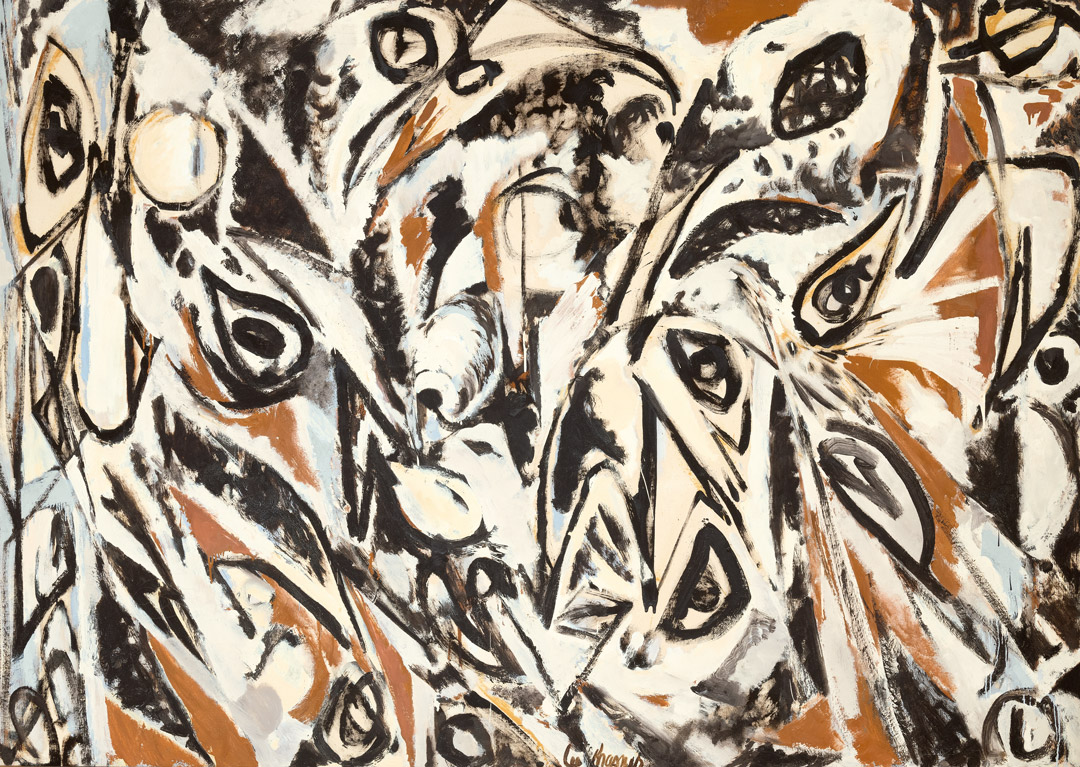

Lee Krasner, Night Watch, 1960

Acquired November 19, 1981

Philip Guston, The Painter, 1976

Acquired February 1, 1982