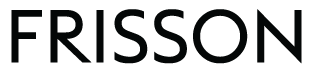

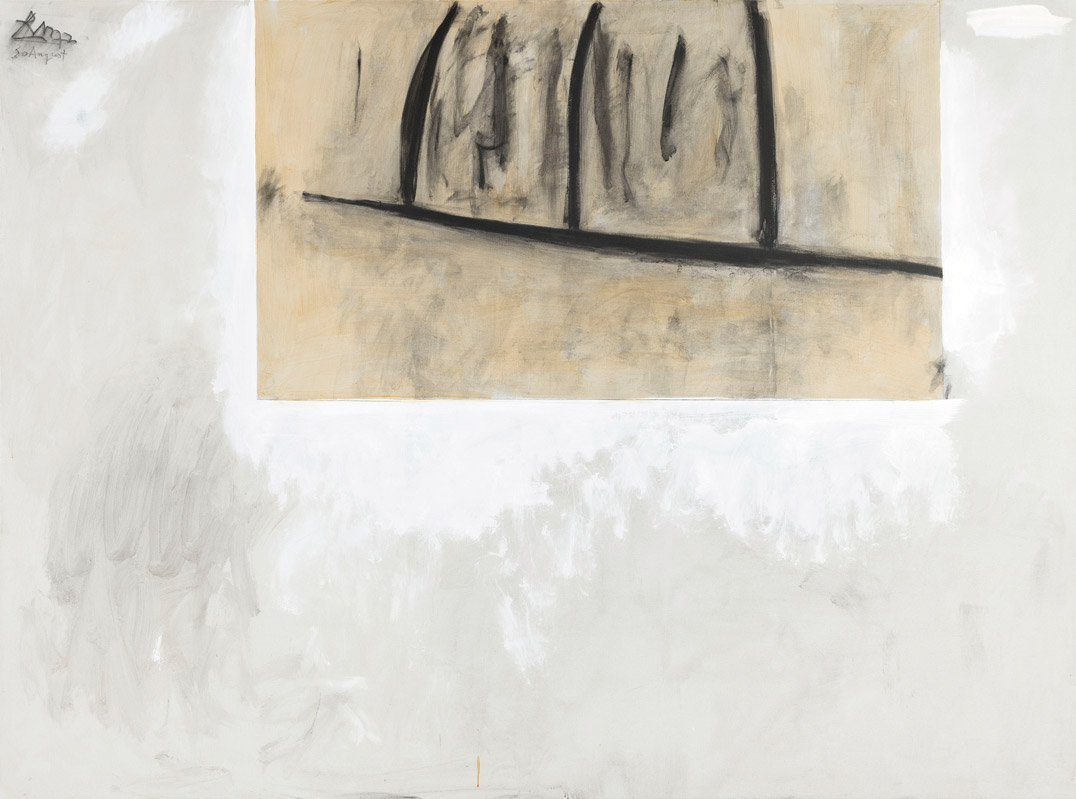

PH-338

1949

Clyfford Still

American (1904–1980), oil on canvas, 91 1/2 × 68 3/4 in. (232.5 × 174.5 cm). Seattle Art Museum, Gift of the Friday Foundation in honor of Richard E. Lang and Jane Lang Davis, 2020.14.17. Photo by Spike Mafford / Zocalo Studios. Courtesy of Friday Foundation. © 2021 The Clyfford Still Estate / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

PH-338

David Anfam

The opening of Clyfford Still’s namesake museum in November 2011 in Denver meant that the reclusive figure—whom a prescient modern art historian had described at the turn of the millennium as “the great unseen”—swung into view as never before.1 Hitherto, approximately ninety-five percent of Still’s corpus had lingered more or less out of sight and unknown. What had remained accessible in public collections and was at least known in private ones now turned into magnificent pendants, especially the grand donations Still granted three US museums,2 to a larger whole. In short, an epic legacy risen from the past, redivivus, for posterity. Its long-term impact looms large enough for Abstract Expressionism’s conventional histories to need revising. Having retained almost everything he made during a sixty-year career, Still thus returned to the limelight in the twenty-first century’s second decade as if from beyond the grave.

The artist’s work in the Lang Collection, PH-338 (1949), sports an outstanding pedigree: it was the sole Still owned by Ben Heller. From the early 1950s onward, Heller amassed probably “the best private collection of Abstract Expressionist painting that ever existed.”3 The provenance also numbers the doyenne of Abstract Expressionism’s dealers, Betty Parsons. The painting went on display at Parsons’s New York gallery in the artist’s penultimate solo show there in the spring of 1950, from which it traveled directly to another at San Francisco’s Metart Galleries, arranged by students in honor of Still’s resignation from the California School of Fine Arts. Lastly, PH-338 was among the four Stills in the Museum of Modern Art’s landmark exhibition The New American Painting, which toured to eight European countries in 1958–59.4 From start to finish, everything about PH-338 is top drawer—even its date, which found Still at the fecund peak of his powers while living and teaching in San Francisco from 1946 to 1950. Indeed, his activities there played a major role in establishing a “San Francisco School of Abstract Expressionism.”5 A short summary about Still’s titles completes the basic facts concerning PH-338.

“Still makes the rest of us look academic.”

Jackson Pollock

In general, Still placed scant importance on nomenclature, preferring instead to let the art stand by itself. Nevertheless, some early canvases bore sparse titles for public identification (for example, the now-lost A Funeral, North Dakota, 1934)6 and the fourteen listed in the brochure accompanying his New York solo debut at Peggy Guggenheim’s Art of This Century gallery in 1946. They almost surely secreted an esoteric symbolism relating to ancient Greek myths about cyclical fate and renewal.7 By the following March, though, the situation became unequivocal. In advance of his initial show with Parsons, Still wrote to her that “the pictures will be without titles—only identified by numbers.”8 Subsequently, he kept these numerical designations after a fashion: PH-338 was once known as 1949-No. 2. Later, the alphanumeric system ceased when Still, aided by his family, began compiling “documentation books” for his oeuvre. Therein, each entry was assigned a “PH-” or similar label followed by a number (though the sequencing follows no particular total order), said abbreviations simply standing for “ph[otographic]” record, for example.9 The painting now known as PH-338 has always spoken louder than whatever titular mantle it has carried anyway. Only the former “No. 2” tag has a special import insofar as it connotes the existence of a “replica,” now held at the Clyfford Still Museum: PH-385, the erstwhile “1949-No. 1” (fig. 1).10 These replicas or multiple versions point, perhaps unexpectedly, to the heart of Still’s practice.

At face value, replicas suggest inauthenticity, reproduction by rote à la Andy Warhol. Yet for Still they had the opposite meaning. He explained:

Making additional versions is an act I consider necessary when I believe the importance of the idea or breakthrough merits survival on more than one stretch of canvas. . . . Although the few replicas I make are usually close to or extensions to the original, each has its special and particular life and is not intended to be just a copy. The present work . . . was closer to my original concept than the first painting, which bore the ambivalences of struggle.11

Although the piece in question was not PH-338, Still’s thinking applies to it and the prior replica, PH-385. True, PH-385 is slightly larger (105 1/2 × 81 in.). Nevertheless, both possess their own strengths and differences, two firsts among equals. If anything, the Lang canvas may have a tighter “grip” about it because the various elements look a tad more compacted, while the pervasive tonality is subliminally darker. Setting aside comparisons, a key point lurks in Still’s mentioning “concept.” Why? The answer involves a trail leading deep into PH-338’s background, the historical sources and sentiments whence it ultimately sprung.12

Versed in ancient Greek philosophy since his youthful days studying for a master’s degree and teaching at Washington State College, Pullman, during the second half of the 1930s, Still knew his Plato (among many another scholarly forebear, from Aristotle to John Ruskin to Friedrich Nietzsche). No specialist knowledge is required to grasp that for Plato, the higher realm of ideas supported phenomenal reality itself. In fact, the material world incarnated the Platonic Idea—the physical replica to the imagination’s metaphysical vistas.13 Paralleling this logic, Still saw his individual works as the “image of an idea.”14 Here, some commentary helps.

Ideas are limitless and therefore able to generate multiple physical manifestations. A diametric opposite to mere “copies,” Still’s replicas exploit the mind’s inherent dynamism, its ability to roam unhindered through time and space. His working process mirrored this freedom. Rather than follow a linear trajectory, Still roved back and forth across his own output, taking earlier imagery to develop its potential into new territory.15 Consequently, PH-338 echoes numerous traits and forms from years beforehand, but recast to the stage where they no longer know themselves. Before enumerating them, it is worthwhile noting that Still couched this dialectical progress in allegory and metaphor:

It was as a journey that one must make, walking straight and alone. . . . Until one had crossed the darkened and wasted valleys and come at last into clear air and could stand on a high and limitless plain. Imagination, no longer fettered by the laws of fear, became as one with Vision. And the Act, intrinsic and absolute, was its meaning, and the bearer of its passion.16

First, Still’s “journey” translates his modus operandi into similes—note the initial “as . . .” signaling the narrative to be an analogy, not a literal description.17 This puts a brake on the pedestrian misreading of Still’s pictorial mechanics as nothing but landscape in disguise—Grand Canyons seen, as it were, through reductive lenses, so that they become non-objective schemata.18 On the contrary, Still’s pictorial heights and depths, the rugged surfaces and sudden luminous outbursts, offer vistas of the imaginative eye rather than an observational gaze (keenly recorded though his initial realist scenes were). Second, the literary critic Dennis Donoghue praises metaphor’s transformative powers on the grounds that it permits the greatest freedom in the use of rhetoric because it exempts language from the local duties of reference and denotation.19 Shift “language” from text to visuality, and this displacement neatly describes how Still’s morphologies function—besides serving to rationalize his recurrent stress on “freedom.” And if Still’s aforementioned quest has more than a hint of the Puritan John Bunyan’s allegory The Pilgrim’s Progress (1678), then it fits his insistence that art’s deepest purpose is ethical.20 As he famously warned, “Let no man under-value the implications of this work or its power for life;—or for death, if it is misused.”21 Hyperbole? Yes and no. Yes, if taken literally. No, if understood metaphorically—for art can liberate the mind from things temporal and thus raise it above intellectual soul murder.22 So what unites everything in Still’s scheme? Ideas. (Notice his capitalization of “Imagination,” “Vision” and “Act,” thereby rendering these abstract generalities into full-fledged nouns native to the psyche.23) In turn, his aim to make ideas concrete in PH-338 bears witness to an old adage stated by the novelist Victor Hugo: “Stronger than all the armies is an idea whose time has come.”24 Finally, PH-338 marks the climax of a biographical and imaginative voyage reaching back some three decades. Encapsulating it sheds fresh light on this painting.

Still first turned to art around 1919–20. His youthful experiences in Canada farming Alberta’s high prairies prompted a perpetual love-hate relationship to nature. On the one hand, the stone-strewn unbroken soil, from which a living had to be “ripped,” was “meager,” the labor involved in cultivating it harsh in the extreme (he remembered times when his arms were “bloody to the elbow shocking wheat”) and the climate, with its summertime droughts and frigid winters, equally daunting.25 On the other hand, he never forgot nature’s sublimity, “the awful bigness, the drama of the land, the men and the machines.”26 Above all, the encompassing horizontality caused the vertical to reign as a supreme signifier of vitality for Still. He ruminated on this formative period: “Mostly the paintings were records of air and light. Yet always and inevitably with the rising forms of the vertical necessity of life dominating the horizon. For in such a land a man must stand upright, if he would live.”27

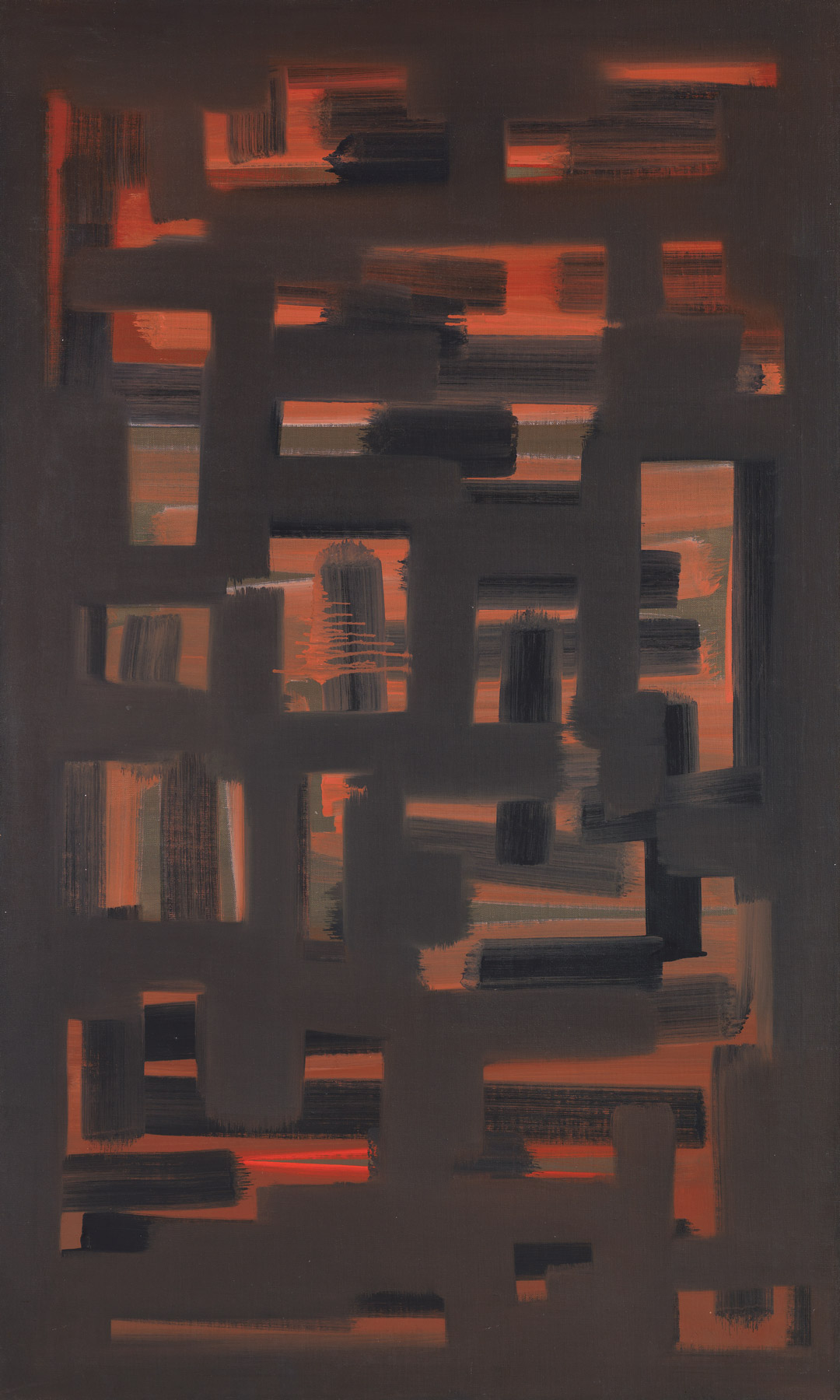

An oil on canvas from 1934 neatly combines most of the themes discussed so far: PH-323 (fig. 2) depicts a striding figure in a darkened valley sparked with a distant glint of light on high.28 The wayfarer’s perpendicular represents a lifeline pitted against the tenebrous expanse surrounding it. His nakedness has an Adamic cast,29 while the setting hints at the biblical “valley of the shadow of death.”30 Already Still has visualized the journey that he would later narrate in 1959—instancing a canny ability to second-guess himself. Still’s ensuing artistic drive was relentless and rapid. Other features in PH-323 that anticipate it include the earth-toned palette ranging from a bright orange-tan (the hellfire at lower right) to deepest umber shadows, relieved by the lone uppermost sky blue, as well as the palette knife’s rough impasto. These structural and chromatic factors endured, except that they grew concentrated to the utmost.

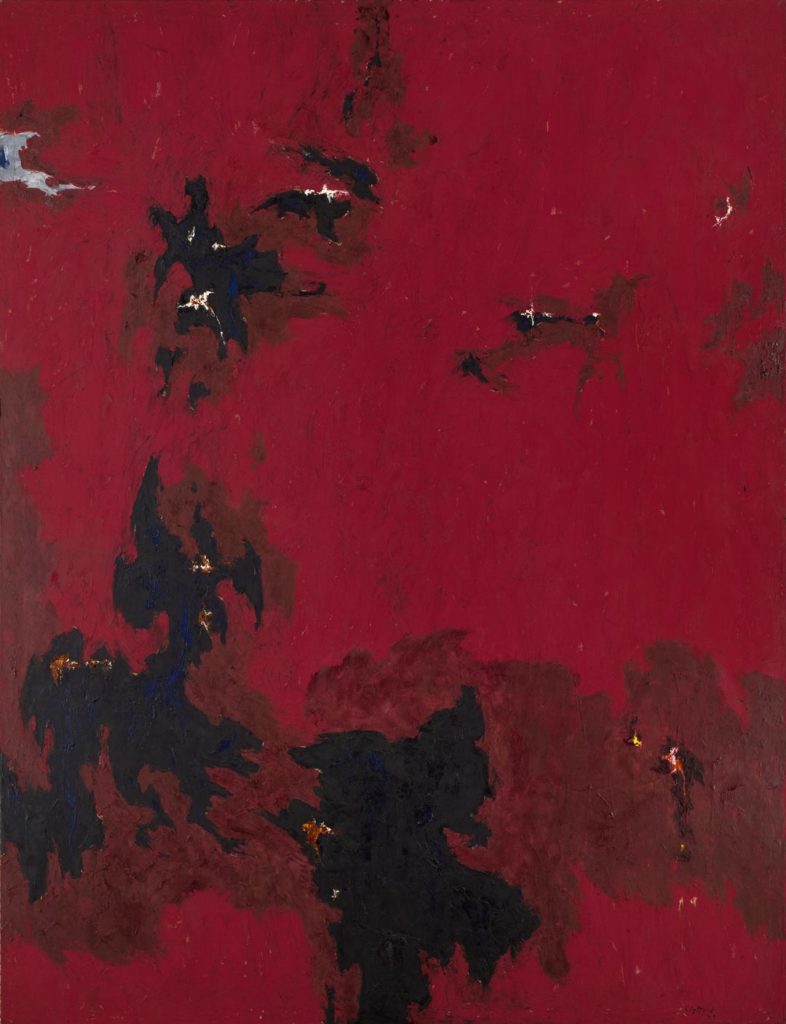

Between 1934 and 1949, Still methodically stripped his verticals and their ambient pictorial masses so that, in his estimate, “by 1941, space and the figure in my canvases had been resolved into a total psychic entity.”31 He also reduced depictive volume to planar silhouettes before simultaneously jamming these shards together and cutting them short at the pictures’ edges. Landscape was never the innermost preoccupation. Instead, it was an existential impulse—no matter how pared to the slightest traces—to survive against hostile forces. As Mark Rothko quoted Still in 1946, the paintings were “of the Earth, the Damned, and of the Recreated.”32 Of course, this was their spirit, not their actual semblance. At stake is a surrogate theology reminiscent of Vincent van Gogh’s aesthetic credo, which pitted earthly misery against redemption through art. Likewise, the Dutch painter’s coruscating radiance and aggressive tactility also surely set an example to be fiercely rewrought (fig. 3).33 By the decade’s end, Still attained the energy labyrinth that is both PH-338 and uniquely his invention.

PH-338’s encrusted surface, its reflectivity ranging from a charred matte finish to a visceral gloss, justifies Still’s claim the following year to have reached “new hypotheses in experience or sensibility . . . explosive forces.”34 The vertical has been laid waste by the planar masses to the degree that figure/ground demarcations no longer occur. Space seems at once imploded and projected beyond the composition’s bounds. Tiny yet intense rifts suggest light trapped within the engulfing, ruddy maelstrom. Excess is everywhere, a violent romantic dramaturgy pushed to a modern point of no return such that the pigment appears to be realizing itself. No wonder Still described these effects as “swords slipped through the belly . . . life and death merging in fearful union.”35 The painting’s presence confronts us as much as we behold its uncanny otherness. Rather than scan, let alone dismantle, this smoldering incandescence—which has few Abstract Expressionist equals, as attested by even Jackson Pollock in the epigraph above—the eye grapples with its dense terribilita. In the last analysis, PH-338 embodies the image of an exceedingly powerful idea-complex.

Author

David Anfam is senior consulting curator at the Clyfford Still Museum, Denver. His exhibition Abstract Expressionism (Royal Academy of Arts, London, 2016–17) was the largest survey of its kind ever held in Europe. Anfam’s many publications include Franz Kline: Black and White, 1950–1961 (Menil Collection, 1994) and the catalogue raisonné Mark Rothko: The Works on Canvas (Yale University Press, 1998), now in its sixth printing.

Notes

Epigraph Jackson Pollock, quoted in Sam Hunter, Masters of the Fifties: American Abstract Painting from Pollock to Stella (New York: Marisa del Re Gallery, 1985), n.p.

1 John Golding, Paths to the Absolute: Mondrian, Malevich, Kandinsky, Pollock, Newman, Rothko and Still (London: Thames and Hudson, 2000), 232. Golding, my postgraduate mentor, ranked among Still’s foremost admirers outside the United States.

2 The Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo; the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

3 Roberta Smith, “Ben Heller, 93, Collector and Dealer Who Embraced Abstract Art Early, Dies,” New York Times, May 6, 2019. Ironically, Still despised Heller, likely because he would have regarded the collector’s ambitions a threat to the priority of the art itself.

4 At the time, Still himself disapproved of his work being shown in the public domain and remained even less favorably disposed toward the Museum of Modern Art.

5 Susan Landauer, The San Francisco School of Abstract Expressionism (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996).

6 The title proffers two interesting technical clues, since it presumably references Gustave Courbet’s A Burial at Ornans (1849–50, Musée d’Orsay). First, the nod suggests that Still would have known Courbet’s use of the palette knife, an implement that Still, too, almost always used. Second, the canvas was six feet high and approximately eight feet wide, indicating that Still was already adopting quite large dimensions, in the spirit of Courbet’s monumentality.

7 David Anfam, “‘Of the Earth, the Damned, and of the Recreated’: Aspects of Clyfford Still’s Earlier Work,” Burlington Magazine 135 (April 1993): 260–69. A title in this show, Siamese Cat and Daughters—hitherto unattached to any known painting—may now be recognized as applicable to PH-355 (1945, Clyfford Still Museum, Denver). My thanks to Chiara Ianeselli for this suggestion. Still asserted that the titles derived from the gallery’s staff.

8 Clyfford Still (March 3, 1947), quoted in David Anfam, “Clyfford Still” (PhD diss., vol. 1, Courtauld Institute of Art, 1984), 121.

9 Canvases and oils on paper were given “PH” numbers, pastels “PP” numbers, lithographs “PL,” etc. The Still family’s preference is not to italicize these assignations, further preventing their being read as quasi-titles.

10 The word “held” is employed advisedly, since the collection belongs to the City of Denver, not the artist’s museum per se.

11 Clyfford Still (July 30, 1972), statement to the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, DC. Unless otherwise indicated, all further documents by Still are held at the Clyfford Still Museum Archives (henceforth CSMA).

12 Still considered his entire oeuvre a totality. Hence, he moved to keep as much of it intact as possible by forming a Gesamtkunstwerk for the future.

13 These and various relevant tenets feature in Murray W. Bundy, The Theory of Imagination in Classical and Medieval Thought (Urbana: University of Illinois, 1927). Bundy was Still’s tutor at Washington State College. Forty years on, Still remained mindful enough to invite him to the opening of his retrospective at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, in 1979. In correspondence with the author in 1978, Bundy had clear memories of his onetime student—so the long-standing recognition was mutual.

14 Clyfford Still to Gordon Smith, January 1, 1959, in Paintings by Clyfford Still (Buffalo: Buffalo Fine Arts Academy, Albright Art Gallery, 1959), n.p.; cf. Bundy, Theory of Imagination, 53, discussing “the image of an idea.”

15 This method may account for certain detractors’ skepticism about the chronology.

16 Still to Smith (1959).

17 Still to Smith (1959): “Although the reference is in a different context and for another purpose, a metaphor is pertinent” (italics mine).

18 The most persuasive statement of this approach remains Robert Rosenblum, Modern Painting and the Northern Romantic Tradition: Friedrich to Rothko (New York: Harper and Row, 1975). Rosenblum compared a 1957 Still to the British Romantic painter James Ward’s Gordale Scar (ca. 1812–14, Tate).

19 See Dennis Donoghue, Metaphor (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2014). At Washington State College, Still also studied literary criticism.

20 Bunyan’s tale is, of course, pure ethics figured as allegory. By no coincidence, Still also confessed to having “Puritan reflexes.” Beware, though, of considering Still a Christian in any conventional sense. “Nietzschean” is a more accurate description of his mindset (and Nietzsche tellingly wagered that there was only one Christian—and He died on the cross).

21 Still to Smith (1959).

22 The contemporary associations of the term “soul murder” should not be confused with my sense of it, which refers to the Norwegian playwright Henrik Ibsen. In Ibsen’s John Gabriel Borkman (1896), “soul murder” means destruction of the love of life.

23 The capitalizations also accord with Still’s wider taste for old-fashioned literary diction (which he probably deemed more authentic than modern vulgarity).

24 A common translated paraphrase of a line from Hugo’s essay The History of a Crime: The Testimony of an Eye-Witness (1877).

25 Clyfford Still, in conversation with Henry Hopkins, notes in Library files, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, quoted in Dore Ashton, The Life and Times of the New York School: A Cultural Awakening (New York: Viking Press, 1973), 34.

26 Clyfford Still, in Thomas Albright, “Clyfford Still: ‘Seeking the Vastness and Depth of a Beethoven Sonata or a Sophocles Drama,’” Art News 79 (September 1980): 159.

27 Still, statement (1972), CSMA.

28 The direction in which the man heads evokes both the arduousness involved (Christian cultures habitually read from left to right, whereas the traveler is taking a sinister—that is, leftward—path) and the American West (which stands, map-wise, to any reader’s left).

29 On the typology of the American “new man”—very much a theme in Still’s writings—see R. W. B. Lewis, The American Adam: Innocence, Tragedy, and Tradition in the Nineteenth Century (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1955).

30 Psalm 23:4.

31 Clyfford Still, quoted in Ti-Grace Sharpless, Clyfford Still (Philadelphia: Institute of Contemporary Art, University of Philadelphia, 1963), n.p.

32 Mark Rothko, Clyfford Still: First Exhibition, Paintings (New York: Art of This Century, 1946), n.p.

33 Still’s familiarity with Van Gogh is beyond doubt. See David Anfam, “Still’s Journey,” in Clyfford Still: The Artist’s Museum, by David Anfam and Dean Sobel (New York: Skira-Rizzoli, 2012), 92.

34 Clyfford Still to Betty Parsons, July 9, 1950, CSMA.

35 Clyfford Still, unpublished typescript associated with the 1950 Betty Parsons show, n.d., CSMA.

Explore the Collection

Sort by Chronology

Sort by Artist

Sort by Author

Franz Kline, Painting No. 11, 1951

Acquired November 13, 1970

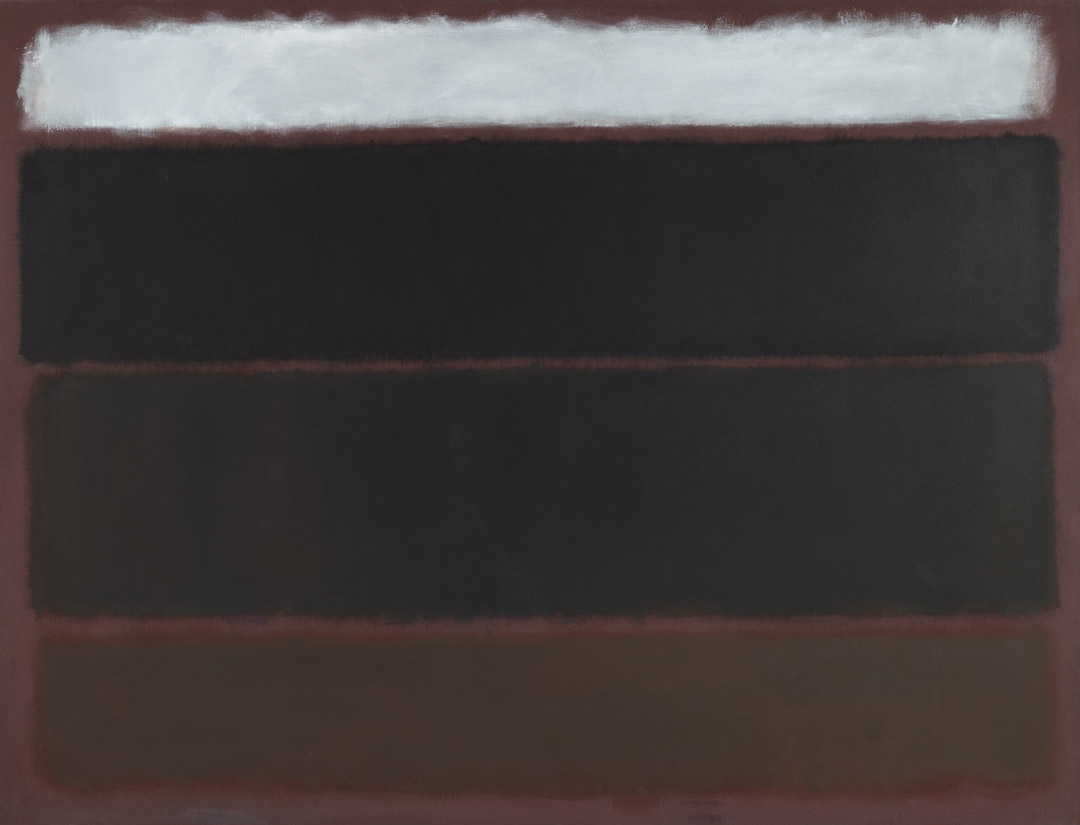

Mark Rothko, Untitled, 1963

Acquired May 18, 1972

Robert Motherwell, Before the Day, 1972

Acquired October 12, 1972

Adolph Gottlieb, Crimson Spinning #2, 1959

Acquired December 11, 1972

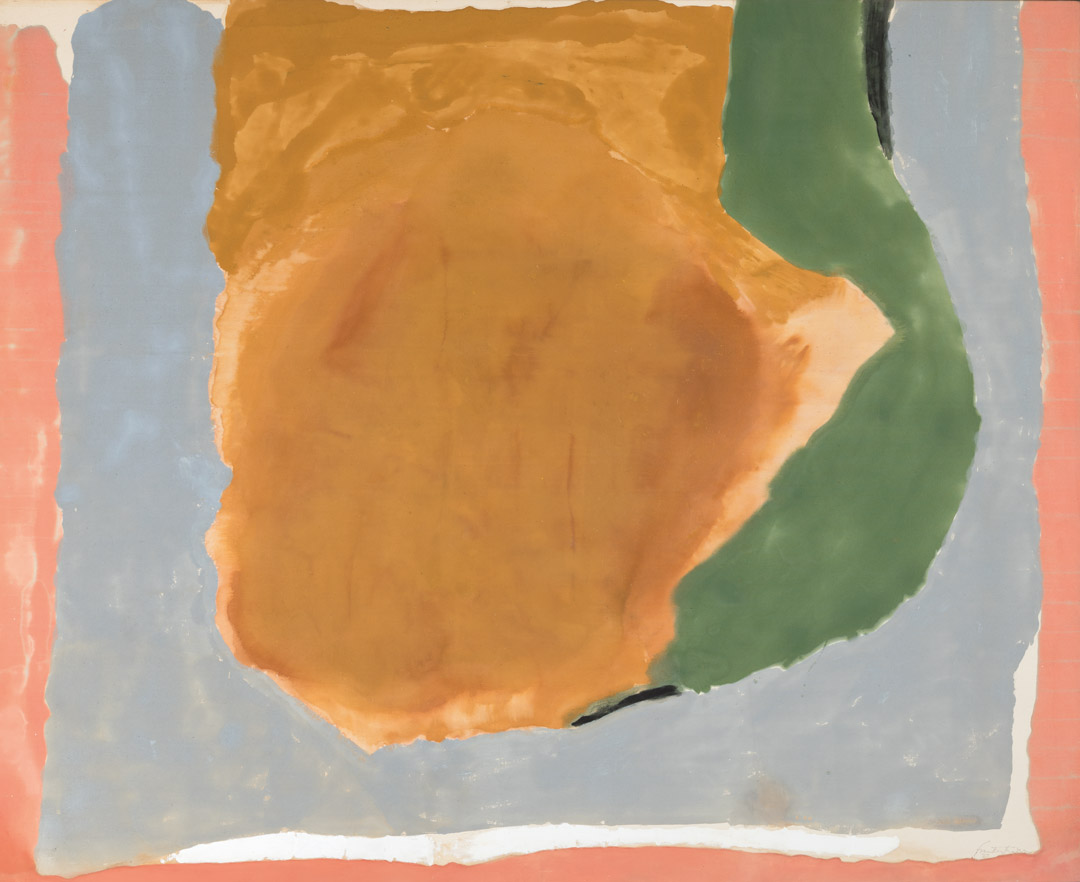

Helen Frankenthaler, Dawn Shapes, 1967

Acquired April 26, 1973

Clyfford Still, PH-338, 1949

Acquired November 10, 1973

Ad Reinhardt, Painting, 1950, 1950

Acquired January 8, 1974

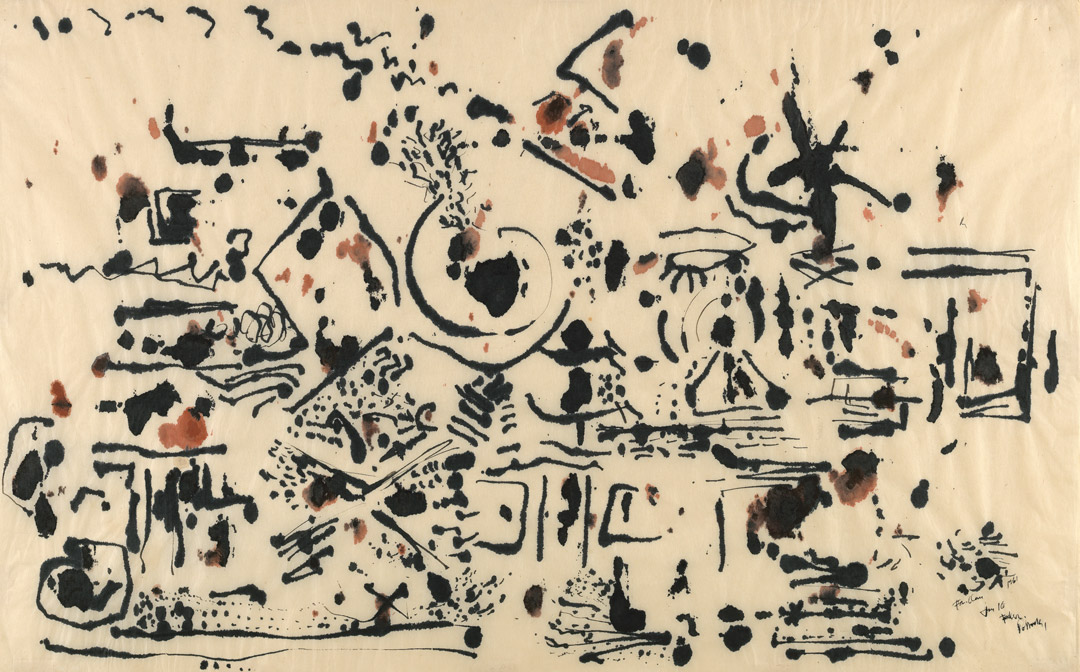

Jackson Pollock, Untitled, 1951

Acquired March 29, 1974

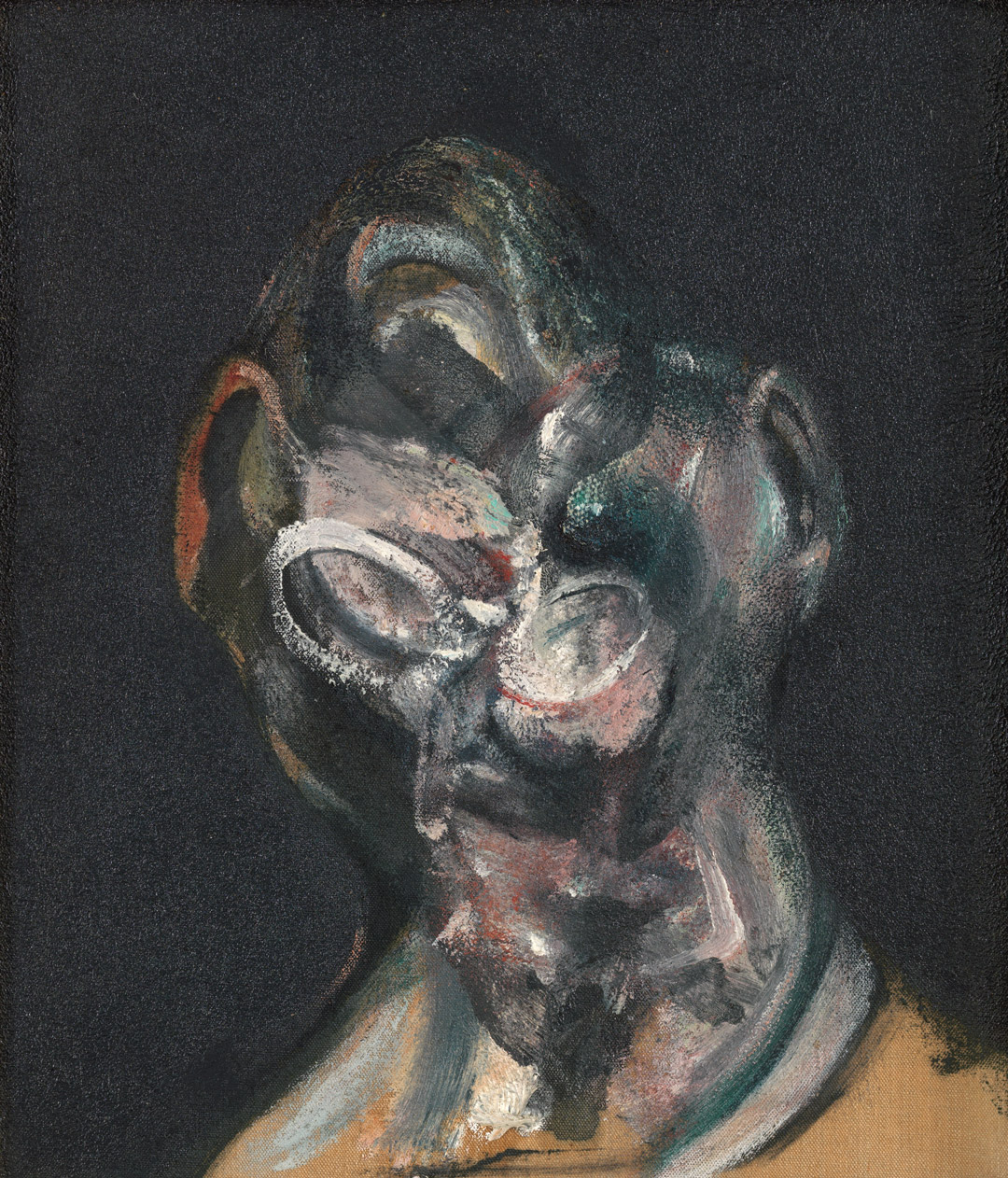

Francis Bacon, Portrait of Man with Glasses I, 1963

Acquired October 24, 1974

Alberto Giacometti, Femme de Venise II, 1956

Acquired January 2, 1975

Robert Motherwell, Irish Elegy, 1965

Acquired November 7, 1975

Francis Bacon, Study for a Portrait, 1967

Acquired November 20, 1976

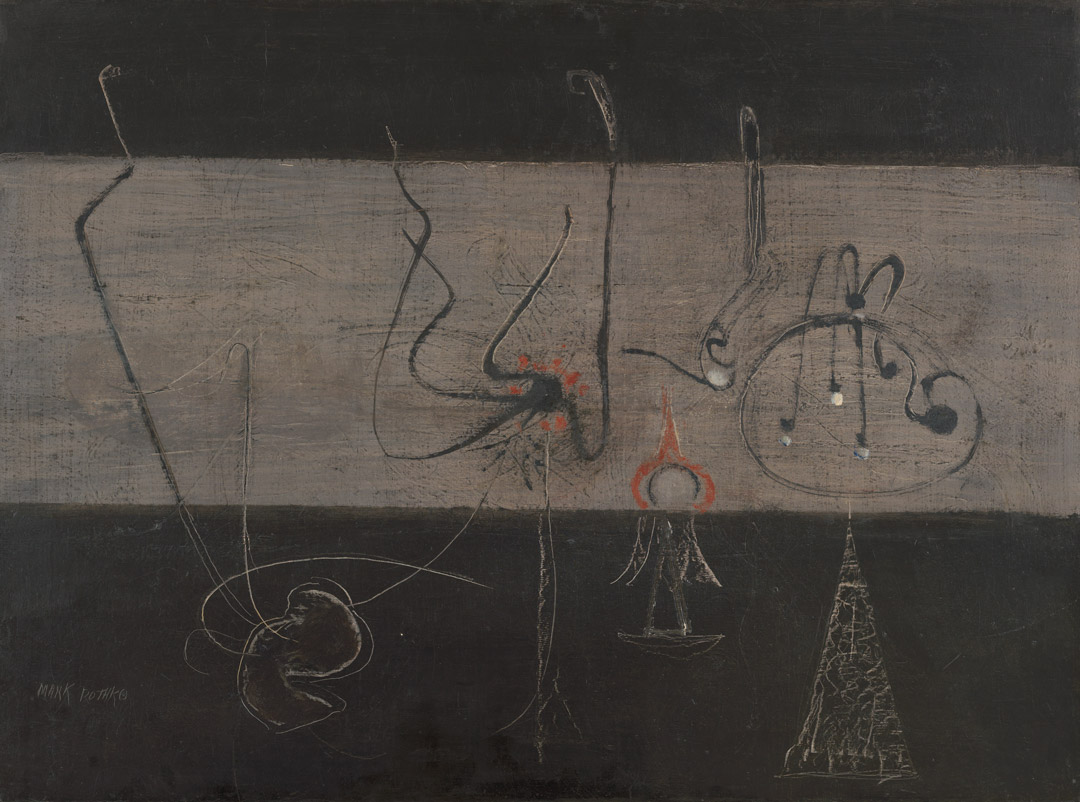

Willem de Kooning, Town Square, 1948

Acquired December 6, 1976

Joan Mitchell, The Sink, 1956

Acquired September 12, 1977

David Smith, Cubi XXV, 1965

Acquired February 22, 1978

Philip Guston, To B.W.T., 1952

Acquired February 14, 1979

Mark Rothko, Untitled, ca.1945

Acquired November 12, 1980

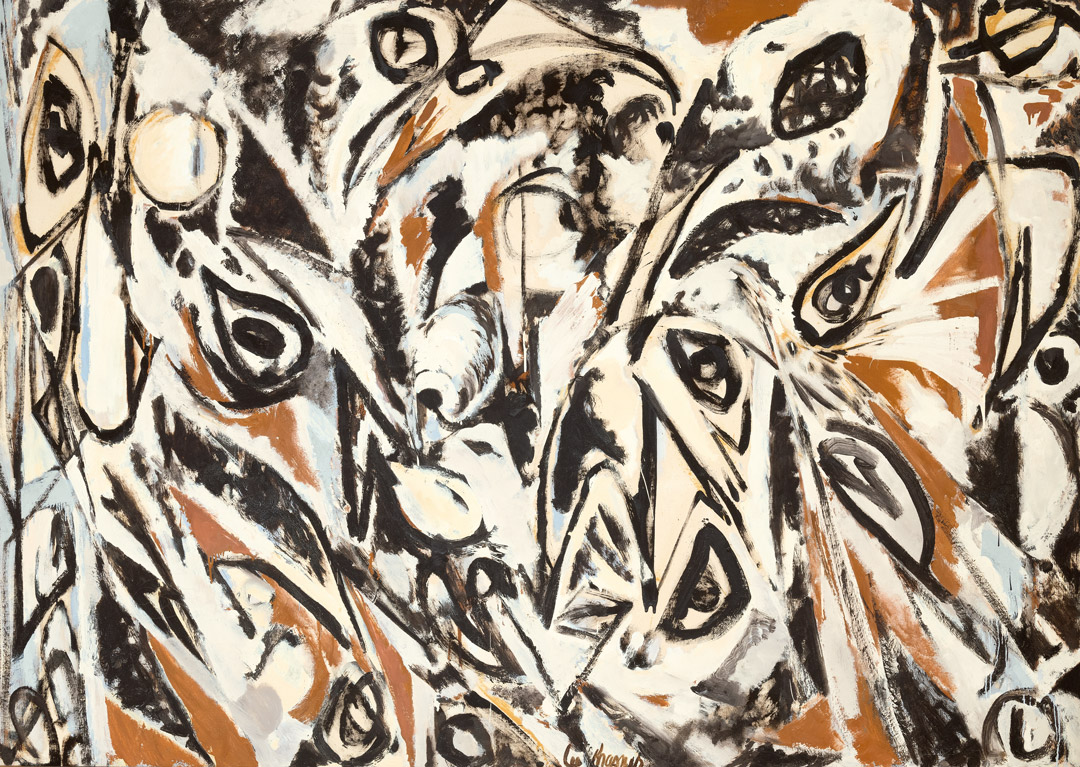

Lee Krasner, Night Watch, 1960

Acquired November 19, 1981

Philip Guston, The Painter, 1976

Acquired February 1, 1982