Cubi XXV

1965

David Smith

American (1906–1965), stainless steel, 119 1/4 x 120 3/4 x 31 1/4, Gift of the Friday Foundation in honor of Richard E. Lang and Jane Lang Davis, 2021.1.2, © 2021 The Estate of David Smith / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Cubi XXV

Michael Brenson

David Smith finished his first Cubi in March 1961 and his twenty-eighth and last Cubi on May 5, 1965, less than three weeks before his death in a road accident near Bennington, Vermont. He made them while the Zigs, Voltris, Voltri-Boltons, Circles, and Wagons, other prominent series, came and went. He made them during the first years of a tumultuous decade in which Pop Art, Minimalism, and Earth Art seized the spotlight from Abstract Expressionism, the movement to which he most belonged. Smith had long pursued many artistic directions at once—his fall 1964 show at New York’s Marlborough-Gerson Gallery “contains works in no less than five styles,” New Yorker critic Robert M. Coates wrote1—but during what turned out to be the last months of his life, the Cubis were his primary focus. In a slide talk at Bennington College on May 12, 1965, he revealed his continuing captivation by stainless steel. From Stonehenge through ancient Greece, Michelangelo to Bernini, Medardo Rosso to Constantin Brancusi and Alberto Giacometti, sculptors had found revelatory ways of animating matter with light. With stainless steel, Smith did too. On his hillside in Bolton Landing, in New York’s Adirondack Mountains, the sun, moon, and clouds seemed to play and even dance over and into the Cubis’ burnished surfaces, in effect painting on them or making them seem like photographic plates, or like membranes or skins. In his iconic photographs of his sculptures set against the hills and sky, Smith had revealed his desire for the landscape to be in his sculpture. In the Cubis, it did participate in the sculpture, and the participation seemed reciprocal. Smith told his Bennington audience that this series, already more numerous than any of his others, was not done with him. “Every time I do four or five I think I’ve exhausted my thinking in that way, but then I buy more stainless steel and make more sculptures. But I hope it finishes off pretty soon.”2

Like Smith’s other sixteen series, the Cubis are distinct in materials and process.3 They are his only series made entirely of stainless steel. While he was known for hands-on involvement in every stage of his work, all the Cubi parts may have been fabricated by Ryerson Steel, and Smith asked Leon Pratt, his assistant, to wield the revolving carborundum disc with which he made the scribbles that turned the surfaces into magnets for light.4 Ryerson tack welded the stainless steel boxes it shipped to Smith, but it was Pratt who sealed their welding, Pratt who welded the parts into place after he and Smith had hoisted the tack-welded constructions so that Smith could adjust them after they had arisen. The Cubis can seem more impersonal than other Smith sculptures; fantasy is less apparent in them than in the twenty-seven Voltris, for example, which Smith made in an abandoned Italian steel factory in spring 1962, assisted by seven workmen whose knowledge and companionship he treasured, in an astonishing burst of creativity.5 But in the Cubis, Smith adds fire and ice to his already mysterious mix of personal and impersonal, subjective and objective, and these combinatory geometries are monumental. The art critic Hilton Kramer felt “an almost terrifying sense of power in them.”6

Indoors and outdoors, the Cubis can seem like entirely different works. “They are designed for outdoors,” Smith said of them, but he wanted his sculptures to hold their own in any setting, and in a museum the Cubis can be intimidating and strange.7 There, embedded in the history of art, their distinctive and often poignant conversations with Impressionism, Brancusi, Cubism, Piet Mondrian, and Abstract Expressionism can be studied. But indoors, the Cubis cannot be as dynamic. On Smith’s hillside, or in a garden or courtyard, their variability can be mercurial, and they can seem to invite gatherings and ritual events. To the poet and curator Frank O’Hara, Smith’s sculpture had one identity outdoors and another in museums. In Bolton Landing, O’Hara wrote:

One was struck by these brilliant and sophisticated stainless steel or painted structures, poised against the rugged hills and mountains, the lake in the distance, and the clouds, an assertion of civilized values not nearly so surprising in the confines of a gallery or museum, where, conversely, these same sculptures took on an aspect of rugged individualism and often an almost brutally forthright power.8

Smith began putting his sculpture outdoors in the early thirties. In the fifties, responding to the increasingly dire problem of storage space and concerned about the treatment of his work by institutions that presented it according to their interests, not his, he began installing his sculptures around his house and shop-studio. By 1960, his sculptural fields had become a work in itself, a proliferating, ever-changing sculptural community. No artist or critic who visited the fields forgot the experience of encountering row after row of sculptures, wild and almost shocking in their diversity, spread across his hillside like a troupe or troops, or like letters in a word or words in a sentence (fig. 1). By May 1965, Smith had installed around eighty sculptures in the fields; some visitors would remember the number as one hundred—or hundreds. In the denser north field, Cubi XXV (1965) became one of the first sculptures visitors saw after entering the property. He installed it parallel to the long driveway, pointing toward the shop-studio and the house, a clue that his sculpture had a grammar and the fields were a script.

Cubi XXV is about ten feet tall, ten feet long, and two and a half feet thick. From front and back—and there is no distinction between them—the sculpture has a left and right side, each of which contains two rectangular boxes, one vertical and one horizontal, perched on top of which is a cylinder extending well over the edge of each horizontal container. The inverted L shapes are welded together along the vertical axis so as to create a sense of formidable adhesive pressure. By contrast, the horizontals and cylinders project outward, and both seem to have the capacity—or perhaps the inclination—to unload, or fire. One cylinder is squat, the other elongated. Although they are separated by only a few feet and appear to have the ability to move, capable of revolving or of sliding along the horizontals like balls on a juggler’s arms, their energy seems not just effusive but also closed in, even imprisoned within their cylindrical bodies. The space between the two cylinders seems a chasm, as thick in its own way as the spaces inside the steel containers, each one like a canister holding a secret that only some future civilization could reveal. With its reflective surfaces, Cubi XXV is visually interactive with its environment, but it may also be physically interactive, an invitation to walk or pause under the lintels. Like an Alice-in-Wonderland road sign, the sculpture seems to say, “Go in this, no, go in that direction.” Or maybe it recalls a story, one of children and parents and family drama. But any narrative thread is discontinuous, and the sculpture cannot be scripted. While it could hardly be more present, here, with us, in so many ways, at the same time it is as if we can’t find it, or even see it.

Cubi XXV belongs to one of the Cubi clusters to which Smith referred at Bennington. In all of the Cubis he made in the late fall of 1964 and January 1965, he is concerned with language and image. Cubi XXIII (fig. 2), which he dated November 30, 1964, includes an upright cylinder that suggests an I and four rectangles that form two inverted V ’s, together suggesting an upside-down w or, more prominently, an m, as well as almost fourteen-foot-long creaturely limbs eager to stride over the earth, and five-foot-tall triangular arches that people, particularly children, can pass underneath. Smith dated Cubi XXIV, the first of the three Cubi Gates, December 8, 1964. Its open, square-like structure suggests a giant letter, an o, but it, too, is architectural—in this case a portal to rest on or step through. Cubi XXVI, dated January 12, 1965, three days after Cubi XXV, is more overtly alphabetic. Its multiple associations include a figure on its back with another figure standing on its belly, a cannon, and a roughly triangular arch, as well as letters that could be read as T, I, and W. TIW were the initials for Terminal Iron Works, Smith’s name for his improbable sculpture factory in Bolton Landing. All letters in Smith’s sculpture, however, drift in and out of legibility, still being discovered, in the process of becoming something else. In Cubi XXIII, the suggestions of I and m—“I’m”—promise a declaration of identity, but the message is forever deferred.

In Cubi XXV, the alphabetic memory is profound. The construction suggests a single letter but also a compound letter, or components that want to be a letter, one that would have the authority of a biblical commandment. But here, too, a letter is not just a letter, or even surely a letter. It is, first of all, image. This particular letter-image recalls ancient image-languages, perhaps including cuneiform—a form of writing that Smith came across in his grandmother’s Bible in Decatur, Indiana, when already as a small boy he was convinced of the violent reductiveness of words. Historically, image preceded language. “A developed system of writing of any kind did not appear before 3,000 BC,” wrote Herbert Read, a critic Smith referred to many times. “Writing, therefore, and the whole conceptual mode of reasoning which depends upon it, is of very recent origin compared with man’s use of visual symbols.”9 In his 1952 essay “The Language as Image,” Smith wrote, “Judging from Cuneiform, Chinese and other ancient texts, the object symbols formed identities upon which letters and words were later developed.” For him, this “development” marked a decline, a loss of fullness and of what Smith called “creative extensions.” The “business and exploitation use” of words, he continued, “has become dominant over their poetic-communicative use, which explains one facet of their inadequateness.” With exceptions, notably James Joyce, who could make words move in multiple directions at once, Smith “resented” the word “world.”10

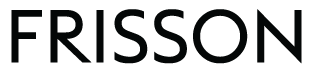

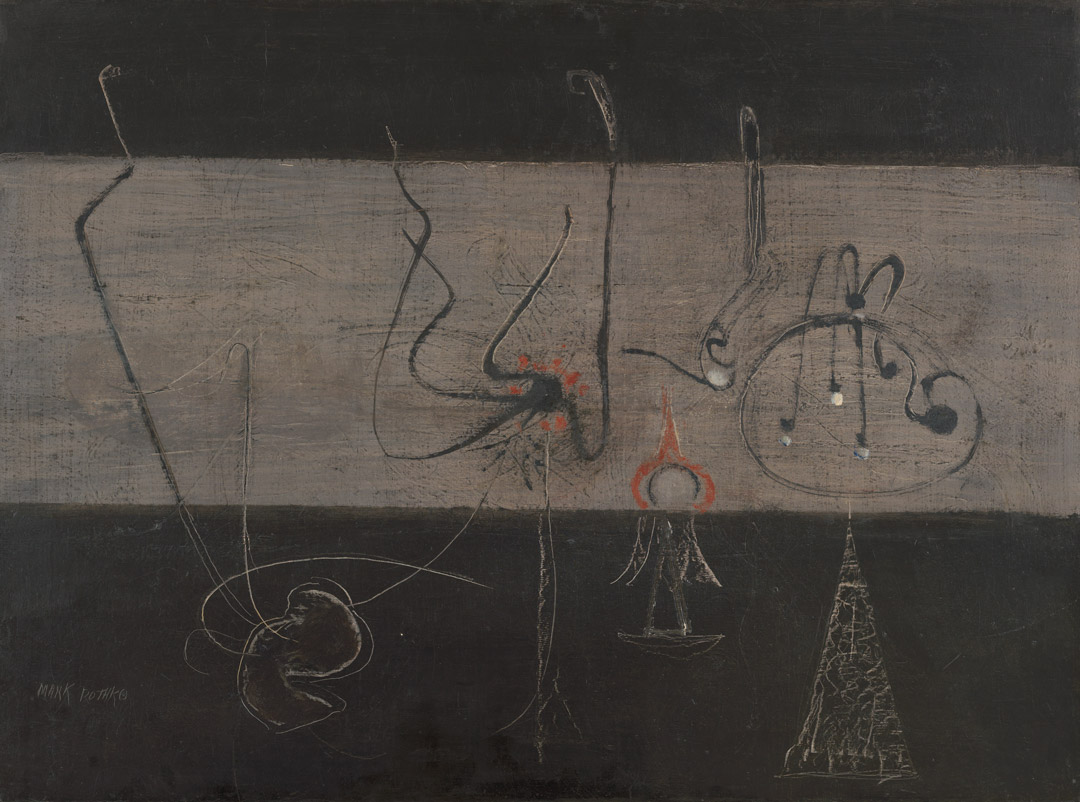

Smith was constantly reinscribing and rephrasing earlier ideas and images. Cubi XXV recalls his 1950 sculpture 17 h’s (fig. 3), in which he welded seventeen small painted-steel forms resembling frontward or backward h’s, to the steel ledges of a tiered three-and-half-foot-tall horizontal and vertical display structure. The stock steel forms appear as letters and as objects—as teeny chairs—and the letters can seem to face off and become musical chairs, or even a script that could turn into a musical score. Cubis XXIII to XXVI also recall another 1950 sculpture, The Letter (fig. 4), in which all eighteen of the steel forms are alphabetic: hints of o’s, y’s, and h’s, and of an n and an I. Each “letter” provides a lens onto, frames, or expands into an image that looks ancient, or even prehistoric, and not so much nonverbal as preverbal. “What do the letters say?” the art critic Emily Genauer asked Smith. He replied: “What any letter says. What Buddy Doran’s letter said in [Joyce’s] ‘Finnegan’s Wake’ . . . ‘You sent for me.’”11 In “The Secret Letter,” his remarkable 1964 interview with Thomas B. Hess, published in the catalogue for Smith’s 1964 Marlborough-Gerson exhibition, Smith again referred to Finnegan’s Wake; its impact on him was as indelible as it was on many Abstract Expressionist painters. “You know the Little Red Hen that scratched up a letter,” Smith said to Hess. “Well I’m always scratching up letters.” Smith returned to the Little Red Hen’s letter later in the interview. “‘You sent for me.’ Something like a very simple little cryptic message,” Smith said. This is “what the secret letter said. I don’t think anybody knows what the secret letter said. . . . All letters say you sent for me as far as I’m concerned.”12

“You sent for me” is a wonderful clue to Smith’s mode of address. His sculpture seems to come from far back and project out, toward the viewer, toward us, with an anticipatory energy that can lead us to believe that it is we who asked for—or sent—for it. It is not just the animation—and mutational desire—of the lines, forms, and surfaces that make the sculpture an offering. Its associative abundance is an offering as well. The Cubis can suggest an array of entertainers—dancers, magicians, acrobats, tumblers, and clowns—all of whom are eager to reward an audience’s desire for enchantment. With their multitude of associations, Smith’s sculptures acknowledge multiple subjectivities. Smith understood perception to be an instantaneous visual response that is almost unfathomable in its undifferentiated complexity. “Perception through vision is a highly accelerated response, so fast, so complex, so free that it cannot be pinned down by the very recent science of word communication,” he wrote in 1951.13 Four years later, he said: “In one flash of time the mind can recall so much vision and action, complex and extensive, that it would take days to relate it.”14 For Smith, perception was not hierarchical, available to one person and not another. “In perceiving I believe all men are equal. . . . No man has sensed anything another has not, or lacks the components and power to assemble.”15 He wanted his sculpture both to be like a perception and to appeal to perception, to be grasped as it was seen. In that perceptual instant, the image sticks. But it is fluid. It keeps moving, and, as it does, it keeps revealing potentialities buried within it. Smith’s sculpture is always prior to a coherence that it points toward but never arrives at. Cubi XXV is a sequence of building blocks that can be imagined and reimagined in different sequences. Smith’s alphabetic signs project the immanence of a message, even as they turn from the verbal toward the image. They encourage viewers to participate in a creative process that is forever expectant, in need of fantasy and thought, and forever against completion.

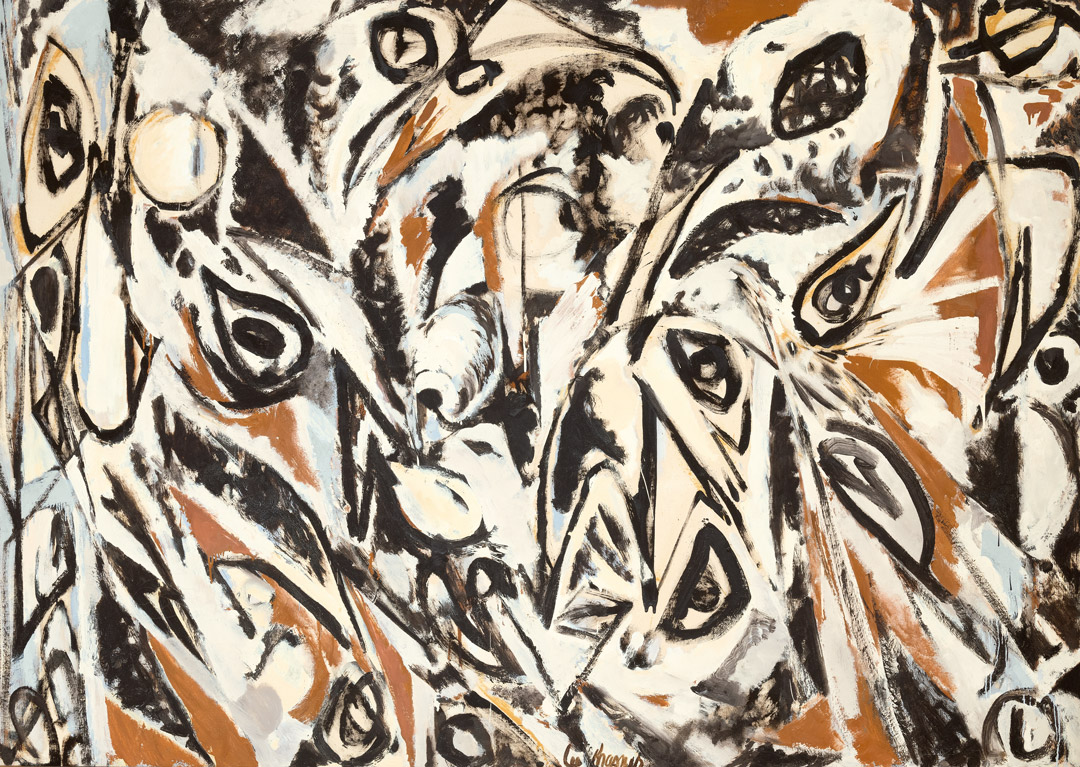

Cubi XXV leads deep into Abstract Expressionist territory. Smith began his artistic career as a painter and never stopped painting. Most of his artist friends, including other Abstract Expressionists, were abstract painters. For many of them too, the making and experiencing of art had an archaeological dimension. Acutely aware that in relation to painting sculpture was considered second class, Smith set out to raise sculpture to the level of painting. Adolph Gottlieb’s Pictographs can be felt in Cubi XXV. So can Barnett Newman’s paintings and sculptures conjuring biblical utterance, and Franz Kline’s gestures that could be the beginnings of architecture or language, and Mark Rothko’s emanations of color in which some energy, some light, seems to be appealing to the viewer, proposing the fullness of perceptual experience. Pollock is a presence, too, if his “drips” are understood as scriptural flow, related to language but shunning and ultimately subsuming it. Smith’s 1951 sculptures Hudson River Landscape and Australia, his signature “drawings in space,” have a tremendous cursive potency. Like Pollock’s landmark paintings, they are haunted by figuration, but they are not worried about it and they want to be experienced as written as well as drawn. “I don’t differentiate between writing and drawing,” Smith told Hess. “Not since I read that part of Joyce. . . . The little red hen scratched up a secret message.”16 Written as well as drawn in space, the image becomes apparitional.

Smith aspired to the eidetic image. “The eidetic image art of the cave man, 30,000 years ago, was reality,” Smith said in 1951. “The directives of my work come from reality. My reality . . . is not one thing; it is a chain of interlocking visions.”17 In the cave art he revered, incised drawing activates painted stone, making its mass seem porous and spatial. Such images were performative. They oriented and presided over, and made the insides of the earth sites for ritual gathering. “Eidetic images,” the curator Kirk Varnedoe wrote,

are forms of waking hallucination, in which normal boundaries between the productions of the mind and the evidence of the senses are broken down, and a subject sees an image of extraordinary completeness and impact, without the person or object in question actually being present to the eye. . . . The eidetic ability elevated the “mind’s eye” to co-equality with visual sensation, dissolving the boundaries between imagination and perception, myth and reality.18

In the eidetic image, what is seen is inseparable from what is remembered, what is remembered from what is dreamed, and what is known from what is felt. Cubi XXV is matter and memory, a precisely delineated constellation of block forms and an afterimage, an attack on the stopped image of the statue and prophetic statuary.

Author

Michael Brenson has written catalogue essays on David Smith for the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, and the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute. He contributed to David Smith Sculpture: A Catalogue Raisonné, 1932–1965 (Yale University Press, 2021), and his biography of the artist, David Smith: The Art and Life of a Transformational Sculptor, will be published in 2022 (Farrar, Straus, and Giroux).

Notes

1 Robert Coates, “The Art Galleries,” New Yorker, November 2, 1964, 165.

2 David Smith, “Some Late Words from David Smith,” 1965, in David Smith: Collected Writings, Lectures, and Interviews, ed. Susan J. Cooke (Oakland: University of California Press, 2018), 428.

3 Seventeen is the number of Smith series determined by the new David Smith catalogue raisonné of Smith’s sculpture. Christopher Lyon, ed., David Smith Sculpture: A Catalogue Raisonné, 1932–1965 (New York: Estate of David Smith, 2021).

4 I’m grateful to Marc-Christian Roussel for sharing his knowledge of the making of the Cubis.

5 The workers were provided by Italsider, the Italian steel company that invited Smith and nine other sculptors to work in its factories throughout Italy and make works for Sculpture in the City, an outdoor exhibition at the 1962 Spoleto Festival.

6 Hilton Kramer, David Smith (1906–1965) (Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1965), 6.

7 David Smith, “Interview by Thomas B. Hess,” 1964, in Cooke, David Smith, 406.

8 Frank O’Hara, “Introduction,” David Smith 1905–1965 (London: Arts Council of Great Britain, 1966), 9.

9 Herbert Read, “Art as a Symbolic Language,” in The Forms of Things Unknown: Essays toward an Aesthetic Philosophy (New York: Meridian Books, 1963), 45.

10 David Smith, “The Language as Image,” 1952, in Cooke, David Smith, 145.

11 Emily Genauer, “Art and the Artist,” New York Post Magazine, April 5, 1969, 14.

12 David Smith, “Interview by Thomas B. Hess,” 1964, in Cooke, David Smith, 390, 408–9.

13 David Smith, “Lecture, Williams College,” 1951, in Cooke, David Smith, 138.

14 David Smith, “The Artist in Society,” 1955, in Cooke, David Smith, 246.

15 Smith, “Lecture, Williams College,” 138.

16 Smith, “Interview by Thomas B. Hess,” 409.

17 Smith, “Lecture, Williams College,” 138.

18 Kirk Varnedoe, “Abstract Expressionism,” in ‘Primitivism’ in 20th Century Art: Affinity of the Tribal and the Modern, vol. 2 (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1984), 651.

Explore the Collection

Sort by Chronology

Sort by Artist

Sort by Author

Franz Kline, Painting No. 11, 1951

Acquired November 13, 1970

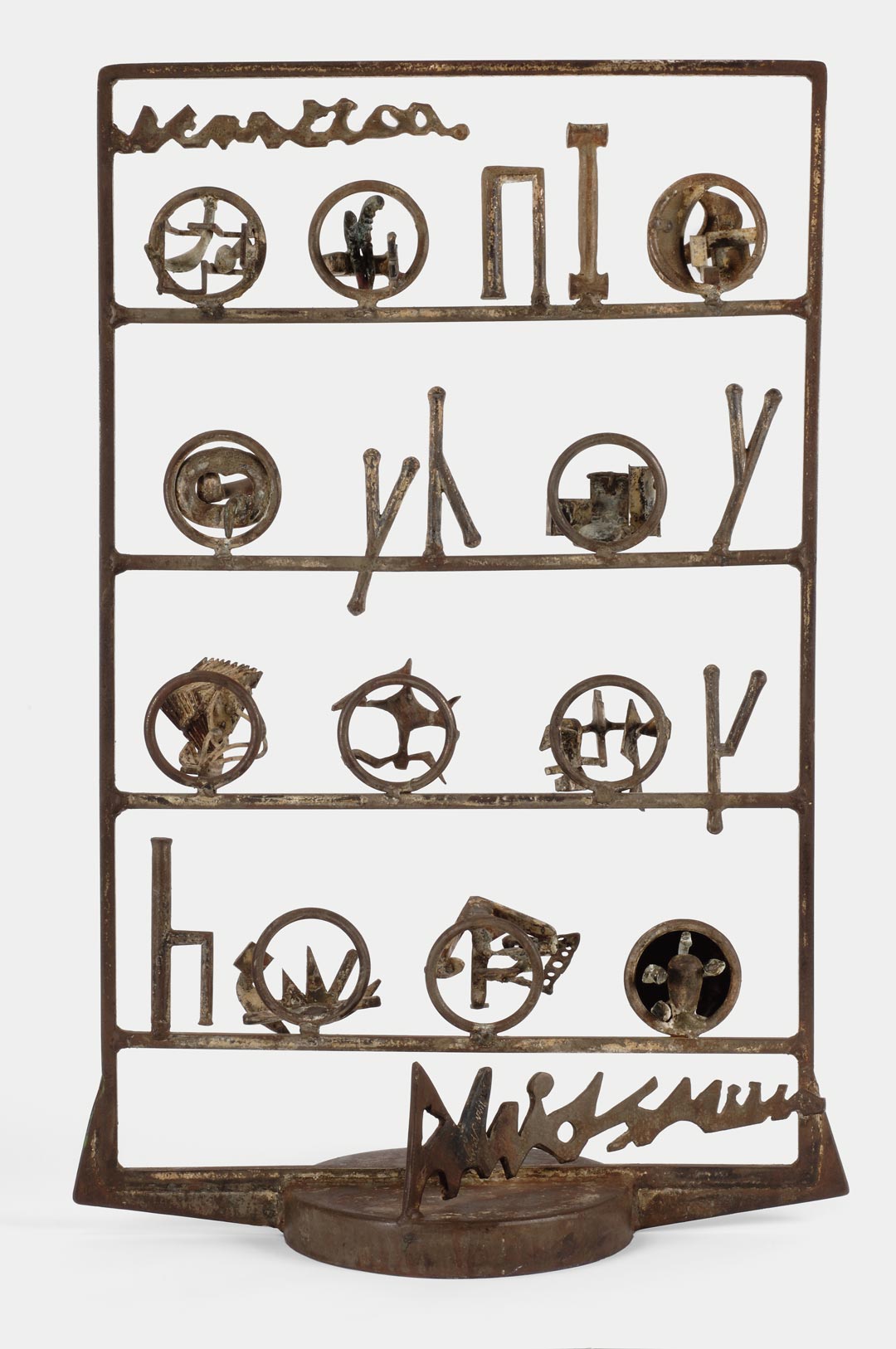

Mark Rothko, Untitled, 1963

Acquired May 18, 1972

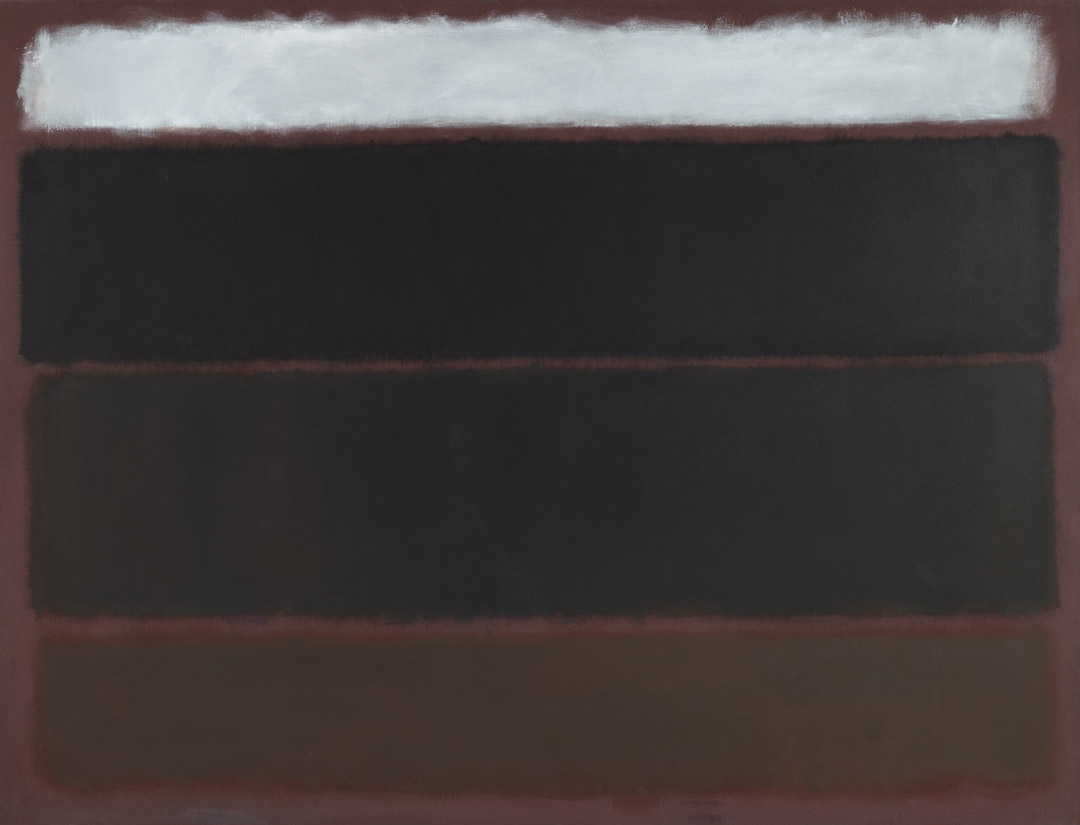

Robert Motherwell, Before the Day, 1972

Acquired October 12, 1972

Adolph Gottlieb, Crimson Spinning #2, 1959

Acquired December 11, 1972

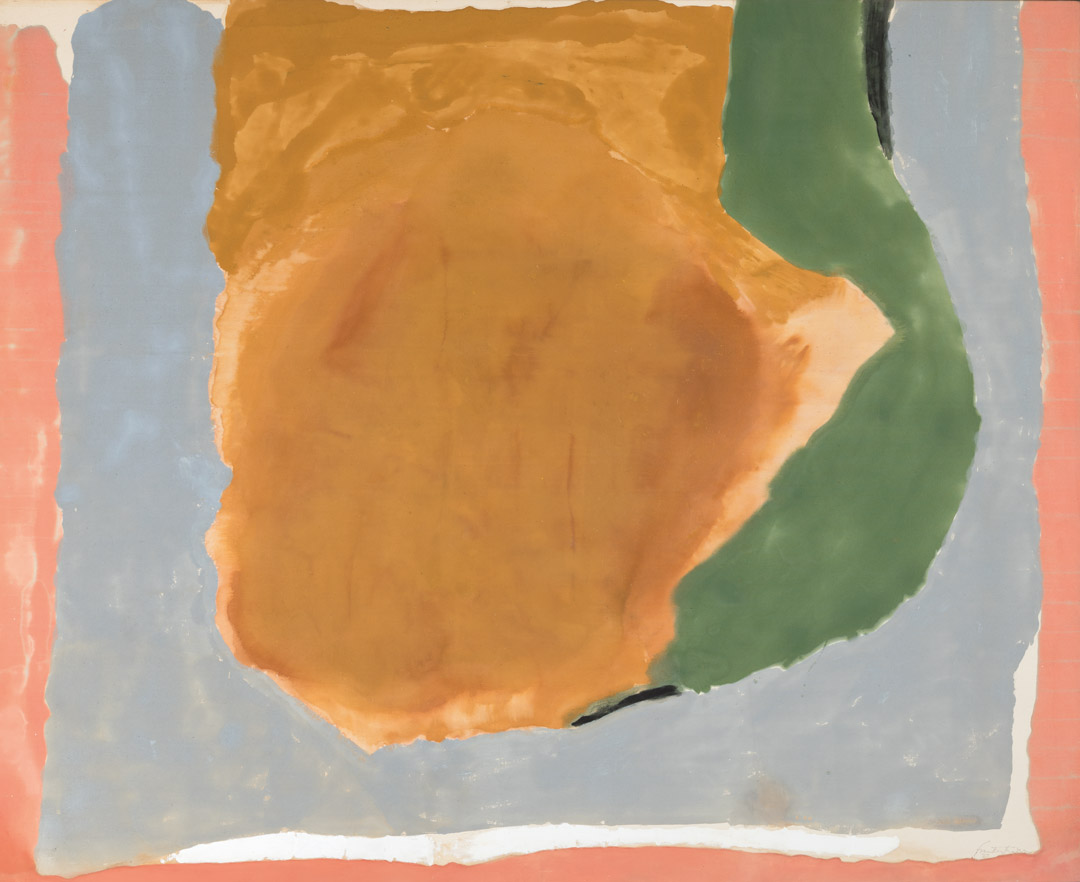

Helen Frankenthaler, Dawn Shapes, 1967

Acquired April 26, 1973

Clyfford Still, PH-338, 1949

Acquired November 10, 1973

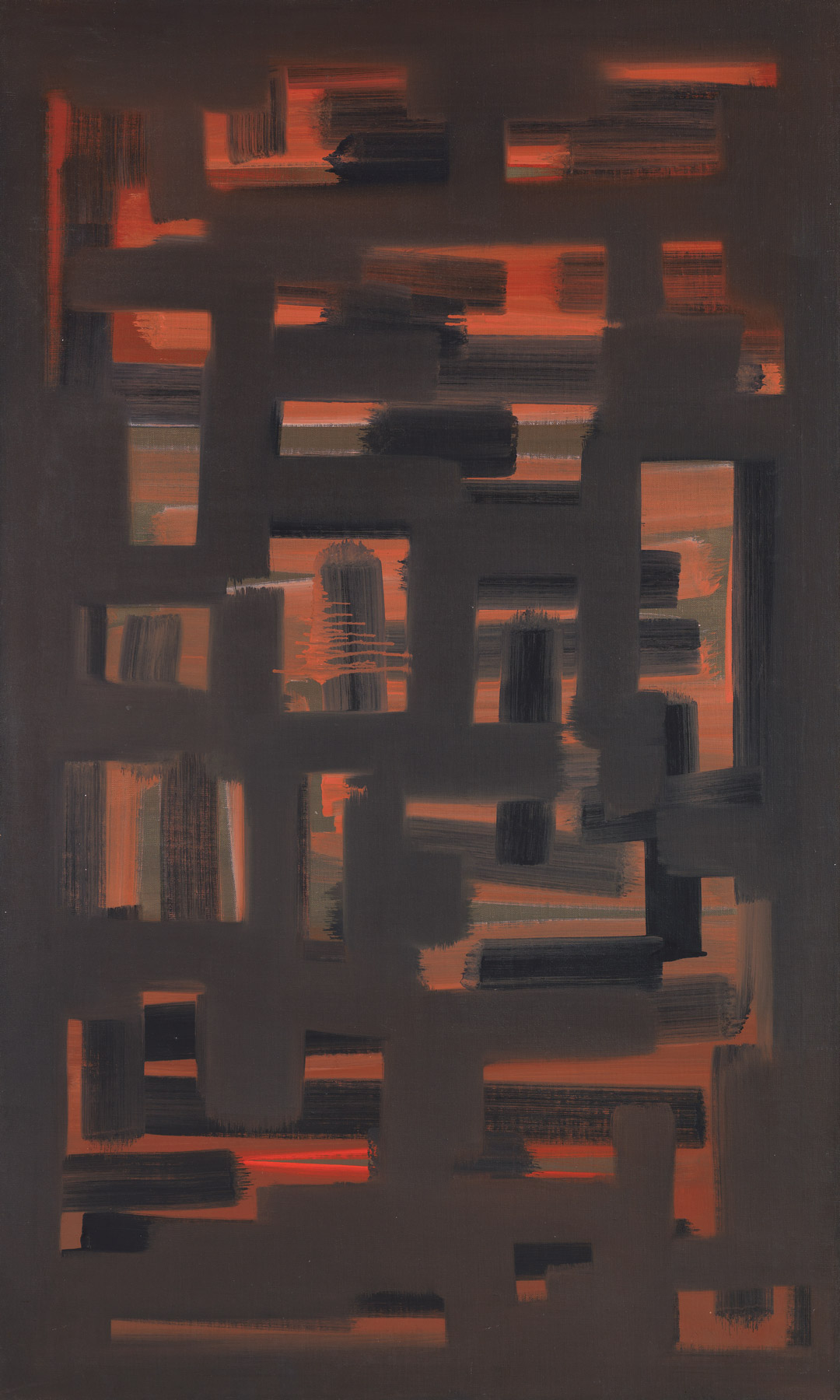

Ad Reinhardt, Painting, 1950, 1950

Acquired January 8, 1974

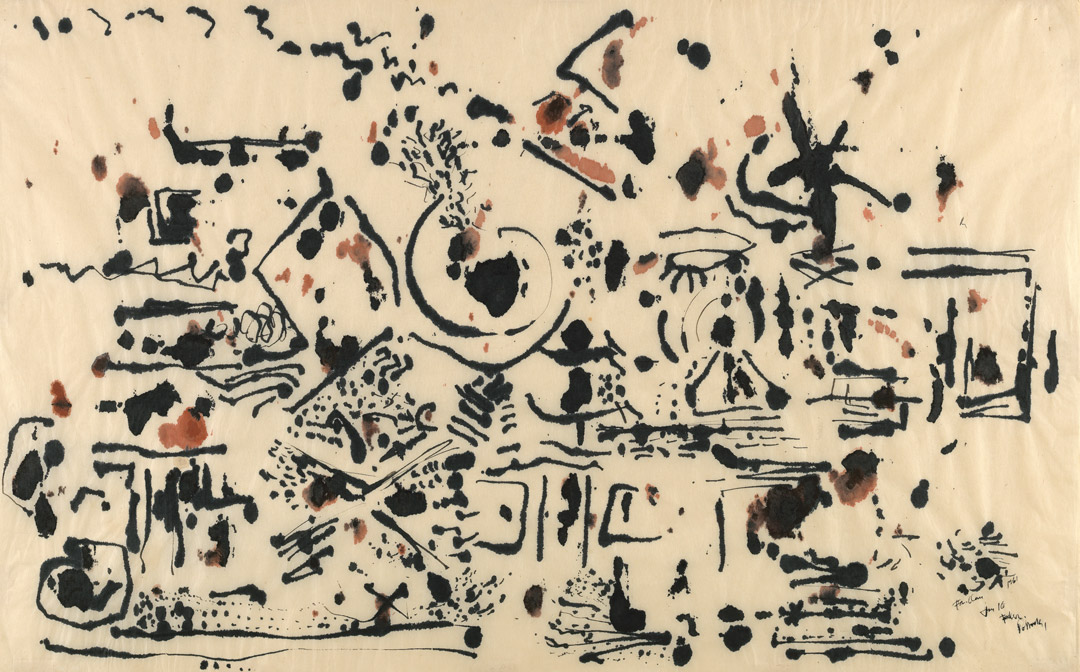

Jackson Pollock, Untitled, 1951

Acquired March 29, 1974

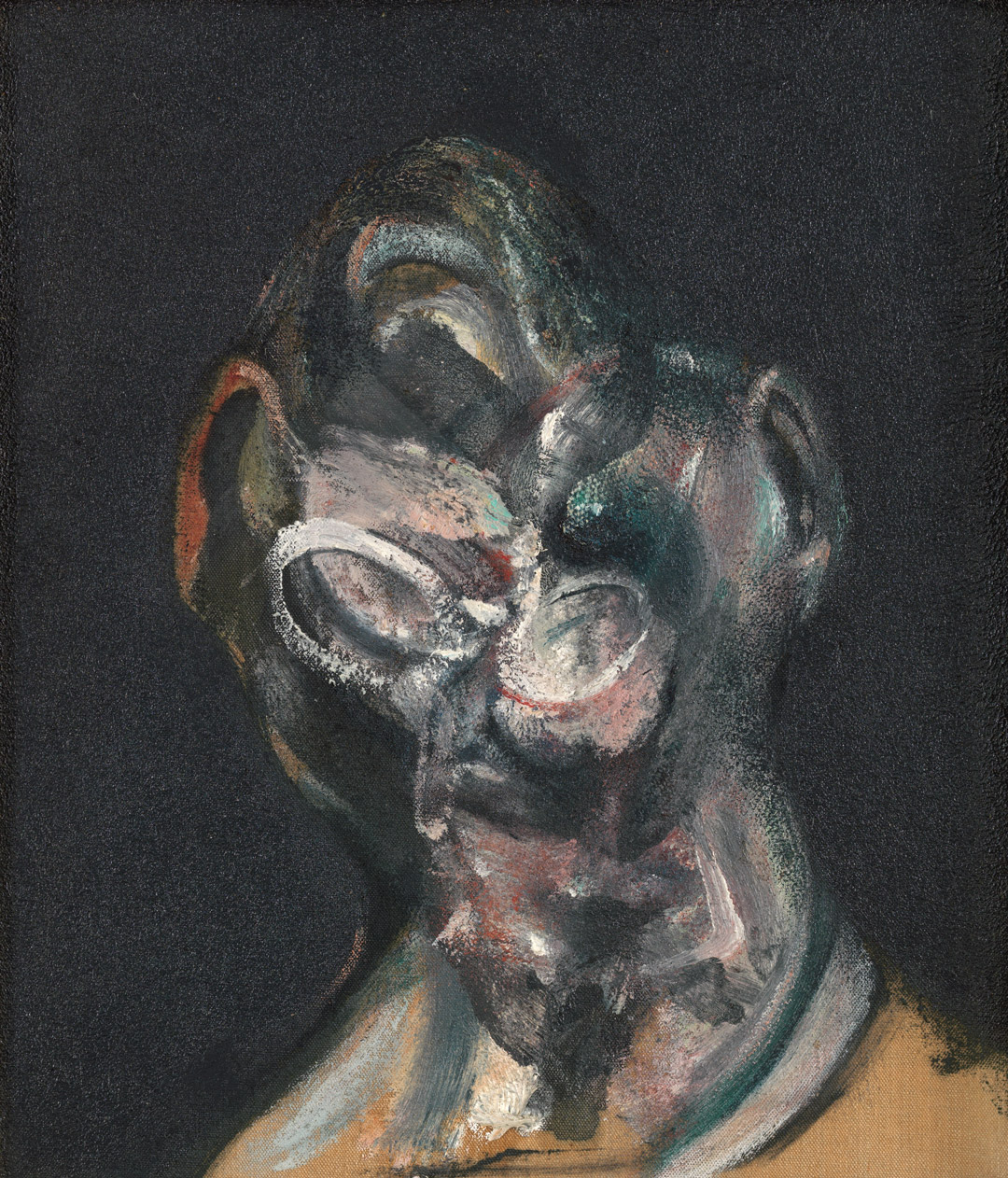

Francis Bacon, Portrait of Man with Glasses I, 1963

Acquired October 24, 1974

Alberto Giacometti, Femme de Venise II, 1956

Acquired January 2, 1975

Robert Motherwell, Irish Elegy, 1965

Acquired November 7, 1975

Francis Bacon, Study for a Portrait, 1967

Acquired November 20, 1976

Willem de Kooning, Town Square, 1948

Acquired December 6, 1976

Joan Mitchell, The Sink, 1956

Acquired September 12, 1977

David Smith, Cubi XXV, 1965

Acquired February 22, 1978

Philip Guston, To B.W.T., 1952

Acquired February 14, 1979

Mark Rothko, Untitled, ca.1945

Acquired November 12, 1980

Lee Krasner, Night Watch, 1960

Acquired November 19, 1981

Philip Guston, The Painter, 1976

Acquired February 1, 1982