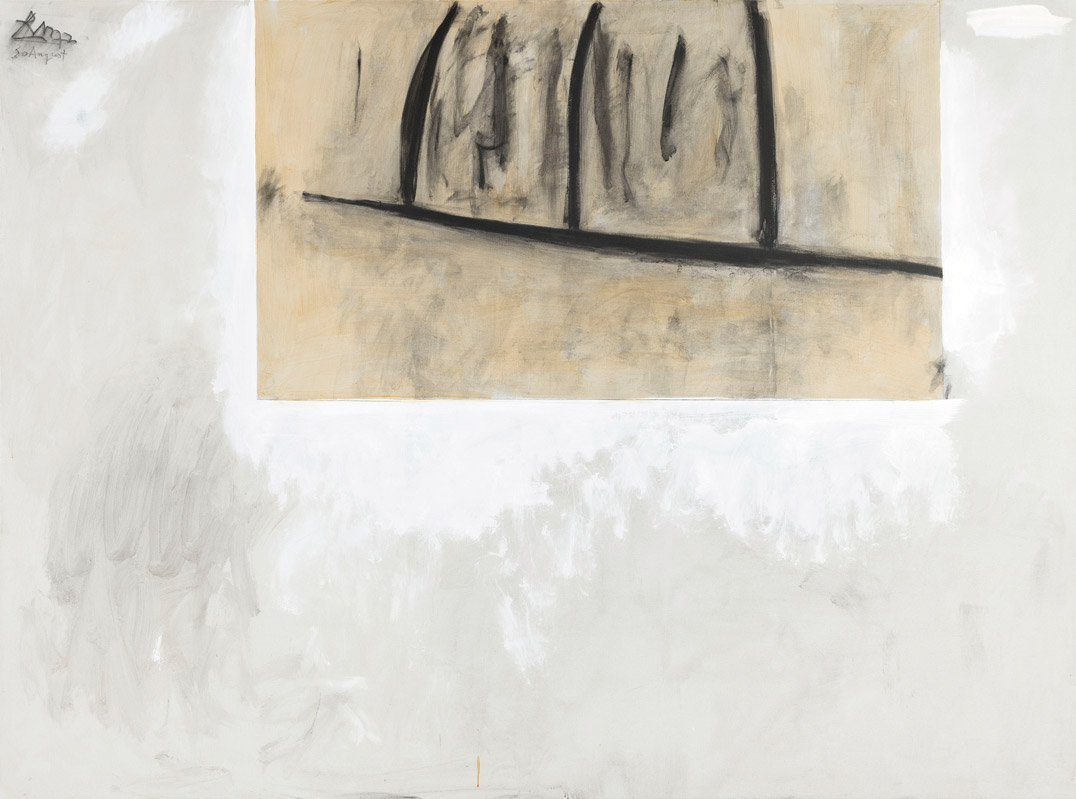

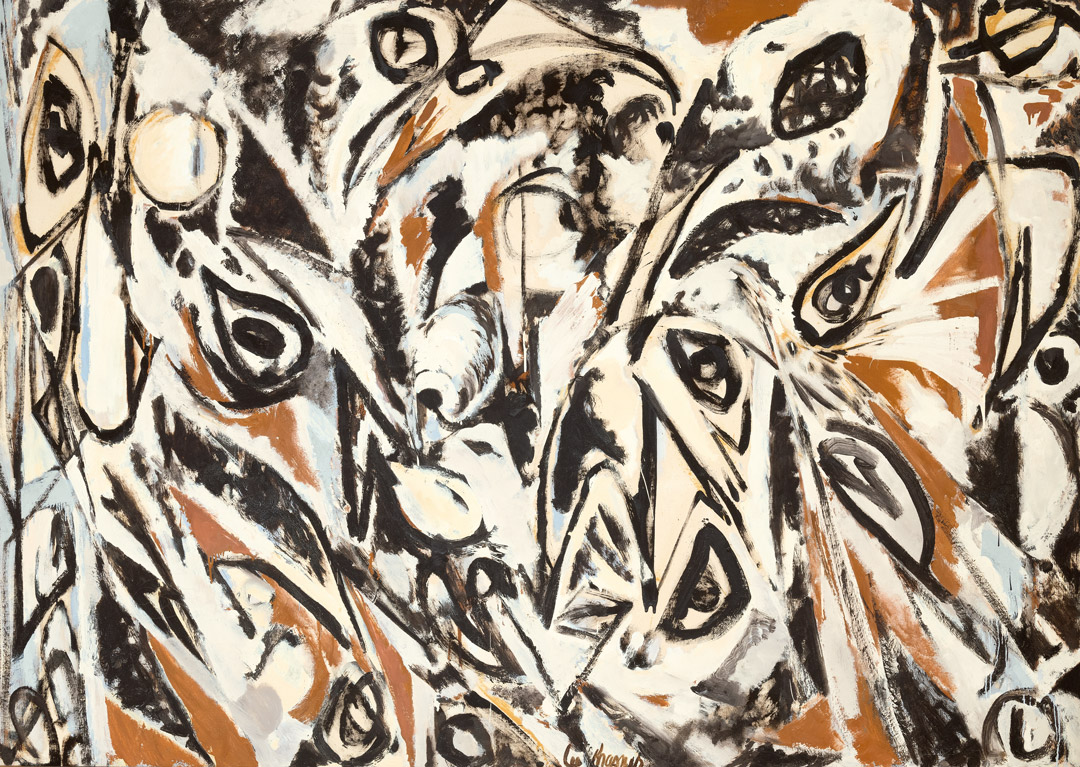

Dawn Shapes

1967

Helen Frankenthaler

American (1928–2011), acrylic on canvas, 77 1/4 × 94 1/2 in. (196 × 240 cm). Seattle Art Museum, Gift of the Friday Foundation in honor of Richard E. Lang and Jane Lang Davis, 2020.14.5. Photo by Spike Mafford / Zocalo Studios. Courtesy of Friday Foundation. Artwork © 2021 Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, Inc. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Dawn Shapes

Elizabeth A. T. Smith

Not yet forty but with close to twenty years of work and significant professional recognition behind her, Helen Frankenthaler was at a mature and self-assured phase of her practice when she painted Dawn Shapes (1967).1 Her bold explorations of abstraction intensified in the 1960s as she probed the coexistence of pictorial structure and atmospheric effects. Stemming from her roots in Abstract Expressionism, these evolving investigations manifest a responsiveness to conditions of climate and place; a desire to infuse her work with a palpable, yet ambiguous, sense of mood; and a keen engagement with old master painting.

Dawn Shapes is both representative of and distinctive within Frankenthaler’s work of the mid to late 1960s.2 Unlike many of her contemporaries who were also prominent abstract painters, such as Kenneth Noland or Frank Stella, she refrained from working in series, asserting that each canvas resulted from a unique set of investigations and describing her practice as “a kind of disciplined free-wheeling.”3 Frankenthaler painted prolifically in 1967. That year, she made paintings vastly different from one another, ranging from bold, monumental works like the luminous Flood (Whitney Museum of American Art) and the magisterial Guiding Red (no longer extant) to the more somber and structured Indian Summer (Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden), with its vertically stacked, quasi-rectangular forms. A compelling example of her singular artistic vocabulary, Dawn Shapes is among the subtler, more introspective works of this period.

Exploring the dynamics of adjacency and containment in Dawn Shapes, Frankenthaler positioned rounded, oblong forms at the center of a zone of contrasting color that seemingly frames the shapes within, mostly surrounded on three sides by a slender band of yet another color. This structure lends a clarity and assertiveness to the composition of forms within forms, while departing from any sort of rigid geometry. Avoiding the use of hard or straight edges in favor of irregular contours, Frankenthaler achieved boundaries between the various zones of color that are simultaneously crisp and tremulous. Points where color/shape come together, abutting or overlapping, convey vibrancy and tension, creating defined but also amorphous edge conditions. Likewise, at the edges of the canvas itself, these forms function as compositional focal points.

In her use of color, Frankenthaler’s approach varied notably from painting to painting. Utilizing an expansive range from bright hues to deeper, darker ones to quieter, pastel tones, she often experimented with surprising juxtapositions of color and frequently modulated the thickness or thinness of the paint to emphasize spatial relationships. In Dawn Shapes, she opted for a palette where adjacencies of more muted colors—mustard, green, and gray tonalities—evoke the shifting, hazy shapes and ambiguity of the early morning light. She employed various additional contrasting colors strategically. Slender areas of black at the top right and lower center of the composition, along with a band of white between the wavering lines of a square of gray and a narrow U-shaped border of salmon pink, deepen and enhance the implied spatiality of the work.

Creating the suggestion of three-dimensional space on a painting’s two-dimensional surface was of consummate importance to Frankenthaler, arising from her early training in Cubism and honed over decades of exploring a more ambiguous abstraction. She once said,

I tried consciously and otherwise to provide space without line, . . . but to delineate line in other ways, meaning if you join a fat shape with a fat orange shape or a green shape or a mud shape, and it’s joined to something else or not to something else or it’s placed in the right spot, then that particular line or formation of color and colors creates a kind of line that moves in space and yet rests on the surface.4

In Dawn Shapes, Frankenthaler achieved a palpable sense of movement and space by deftly orchestrating these elements. Zones of the painting are rife with evidence of the artist’s gestures and process, wherein she not only deployed the “soak-stain” technique of pouring thinned acrylic paint onto a canvas laid on the floor but also utilized a variety of tools and instruments to swiftly guide and modulate its flow.

Of foremost significance in Dawn Shapes is how Frankenthaler configured and manipulated the predominant area of ochre at the painting’s center. Here, she achieved a nuanced range of yellow and more earthen hues—from dark mustard to dusky orange to peach—applied through a combination of pouring and brushwork to enhance the subtlety of the variations in density and tone. The resulting form, while emphatic, lacks clear definition, evoking various possible associations, from the mutable conditions of visibility at dawn to the gathering of storm clouds and the emergence of sunbeams peeking around and through them. This suggested condition of indistinctness gave rise to the title she ultimately chose for the work.

Despite the presence of allusive qualities, Frankenthaler frequently emphasized that the origins of her work were internal and formal. “I work intuitively and without objects,” she said to a reviewer of a 1971 exhibition in which Dawn Shapes was included.5 Acknowledging Frankenthaler’s intentions to achieve an ambiguous statement with her work, the reviewer commented, “If a form appears that someone recognizes, we gather that the painter feels that the viewer himself has created it in his own imagination. Yet there is a feeling of life in all her forms, as though the very warp and weft of living has been translated visually.”6

Dawn Shapes relates compositionally to other paintings in Frankenthaler’s corpus of work. Small’s Paradise (Smithsonian American Art Museum ), Interior Landscape (San Francisco Museum of Modern Art), Buddha’s Court (Private Collection), and Tangerine (Private Collection), all from 1964, present centrally positioned irregular forms “framed” by bands of contrasting color around the perimeter of the canvas. In the mid to late 1960s, she made various works centering on large rectangular or oblong shapes that anchor their compositions visually and spatially. The dominant forms in those paintings, however, tend to be markedly slenderer and more elongated than the eccentric, bulbous ones in Dawn Shapes.

This tendency aligns with an awkward formal asymmetry found in other paintings of the mid-1960s such as Canyon (1965, Phillips Collection) or Coalition (1968, fig. 1)—the former with a predominantly square shape and the latter with a largely circular shape at center, edged by borders of contrasting colors. Frankenthaler once stated, “Instead of ‘mastery,’ you want to be—well, two words I frequently use—clumsy or puzzled. Now clumsy or puzzled are not exactly mastery, but they often lead to the same risk or another word I use: magic.”7 She embraced and consciously pursued this quality of awkwardness across the decades of her practice; she well understood that this element infused her work with a sense of freshness and vitality.

An additional related feature in certain of Frankenthaler’s paintings of this period is the presence of banner-like shapes that seemingly “hang” within the space of the canvas. In Mauve District (1966, fig. 2), for instance, a ragged-edged rectangle of mauve appears to balance off-kilter in the lower area of the composition, exerting a powerful gravity tempered by a touch of whimsy. Frankenthaler’s arguably best-known work of this type is The Human Edge (1967, Everson Museum of Art, Syracuse University), its chosen title underscoring her preference for the impact of the imperfect, irregular gesture. The gray field in Dawn Shapes, functioning visually as a backdrop or surround for the ochre and green forms, reveals a kinship with the elements in these paintings.

Yet the structure of Dawn Shapes, revolving around the relationship between the forms at center and along the edges, is inflected differently. Its rising, swelling central shapes, floating balloon-like in an airy arena, connect to but seem almost untethered from the top of the canvas, creating a suggestion of infinite spatial extension. The condition of ambiguity that Frankenthaler sought to achieve in her work is pronounced in Dawn Shapes. As the poet and critic Bill Berkson commented in 1965, “Frankenthaler leads you through a labyrinth of speculations about placement, scale and meaning and back out to the picture itself as an aesthetic statement of fact. Her more difficult works reject associations as quickly as you can make them.”8 And as the art historian Anne Wagner later astutely observed, “In Frankenthaler’s hands painting moves farther toward its redefinition as a practice that is both arbitrary and intended as well as both figurative and abstract, produced of moves and gestures whose effects are as decisive as their motives are hard to specify.”9 For Frankenthaler, these characteristics resulted from the intertwining of an intuitive and highly considered approach to painting in which ambiguity and awkwardness yielded a sense of visual and interpretive boundlessness. In Dawn Shapes, the complexity of color, subtle implication of anthropomorphic form, and an almost disorienting atmospheric spatiality coalesce as a subdued yet compelling statement by an artist whose approaches to abstraction ranged broadly over the decades of her practice.

Author

Elizabeth A. T. Smith joined the New York–based Helen Frankenthaler Foundation as its first executive director in 2013, following a career as a curator at museums in Los Angeles, Chicago, and Toronto. Her writings on Helen Frankenthaler include an essay in Abstract Climates: Helen Frankenthaler in Provincetown (Yale University Press, 2018).

Notes

1 By this time, Frankenthaler had shown extensively in national and international contexts ranging from the landmark 1951 9th Street Exhibition of Painting and Sculpture in New York City, where she was the youngest participant; to the Première Biennale de Paris in 1959, at which she won first prize in painting; to the 1966 Venice Biennale, where she was one of four artists representing the United States. Beginning in 1951, her painting had appeared in numerous solo exhibitions throughout the United States and Europe, and important museums had begun to acquire her works. In 1960, the poet and art critic Frank O’Hara had surveyed her work of the previous decade at New York’s Jewish Museum, and in 1969 it would be the subject of a midcareer retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art that then traveled to Europe.

2 Frankenthaler painted two works titled Dawn Shapes. The first, from 1963 (Private Collection), was painted in oil rather than acrylic and measures 677/8 × 571/2 in. (172.4 × 146 cm).

3 Helen Frankenthaler, quoted in Irene Heywood, “Twenty Years toward Instant Success,” Montreal Star, February 28, 1971.

4 “Helen Frankenthaler Interviewed by Nancy Miller at Her East 83rd Street Studio, New York, 1977,” produced by Chris Crossman, Video Vasari, April 7, 1977, U-Matic, 26:34. Courtesy of Albright-Knox Art Gallery.

5 Frankenthaler, in Heywood, “Twenty Years.”

6 Heywood, “Twenty Years.”

7 Helen Frankenthaler, quoted in Cindy Nemser, “Interview with Helen Frankenthaler,” Arts, November 1971, 53.

8 Bill Berkson, “Poet of the Surface,” Arts, May–June 1965, 45.

9 Anne Wagner, “Pollock’s Nature, Frankenthaler’s Culture,” in Jackson Pollock: New Approaches, ed. Kirk Varnedoe and Pepe Karmel (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1998), 192.

Explore the Collection

Sort by Chronology

Sort by Artist

Sort by Author

Franz Kline, Painting No. 11, 1951

Acquired November 13, 1970

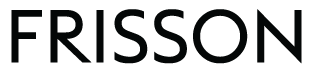

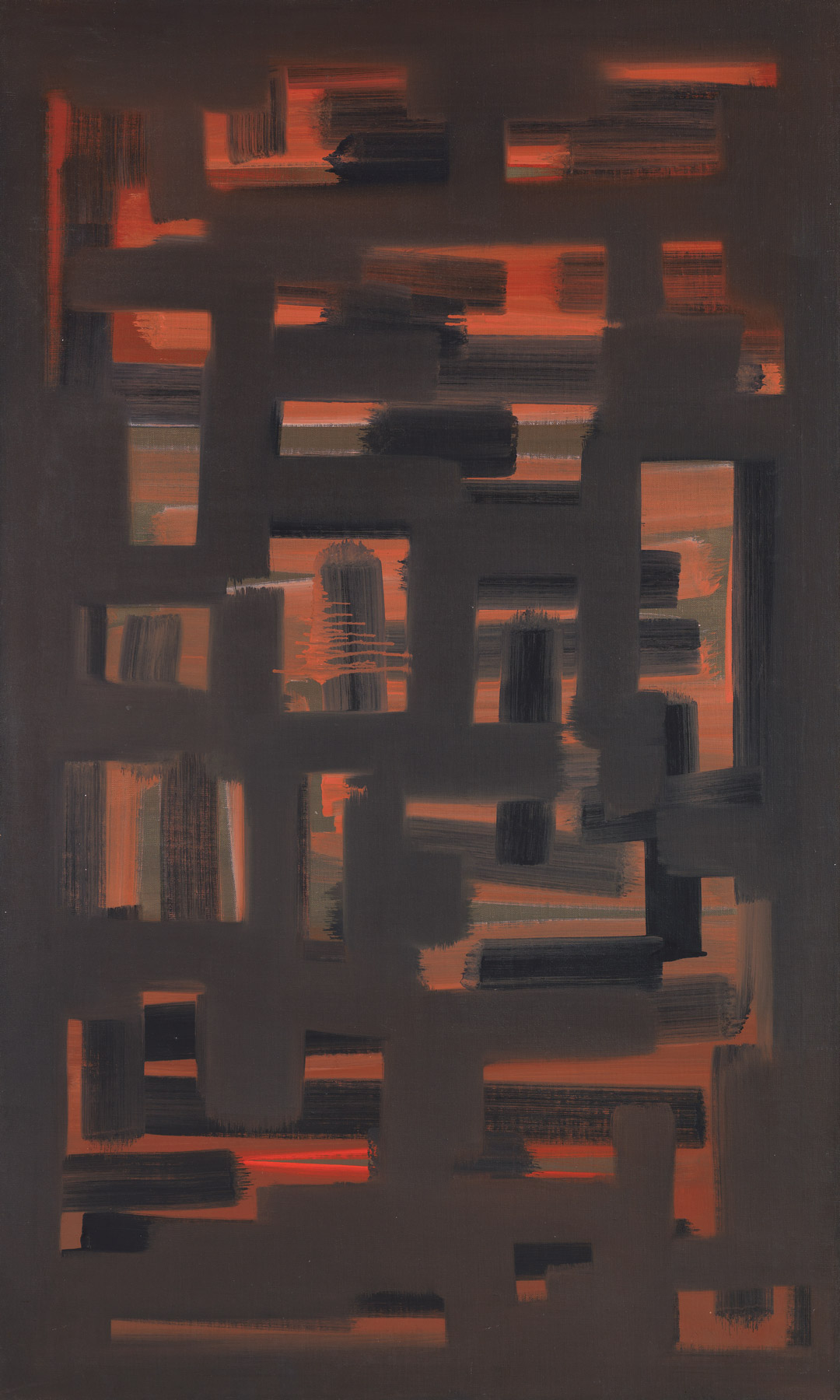

Mark Rothko, Untitled, 1963

Acquired May 18, 1972

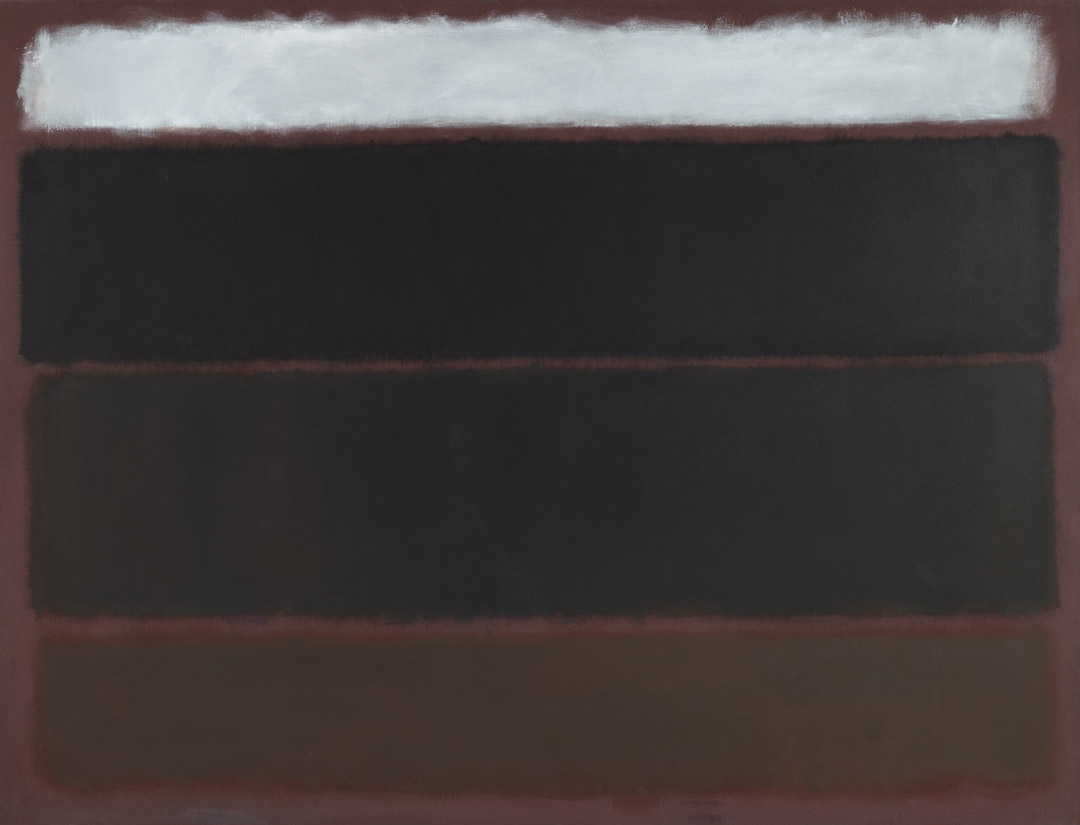

Robert Motherwell, Before the Day, 1972

Acquired October 12, 1972

Adolph Gottlieb, Crimson Spinning #2, 1959

Acquired December 11, 1972

Helen Frankenthaler, Dawn Shapes, 1967

Acquired April 26, 1973

Clyfford Still, PH-338, 1949

Acquired November 10, 1973

Ad Reinhardt, Painting, 1950, 1950

Acquired January 8, 1974

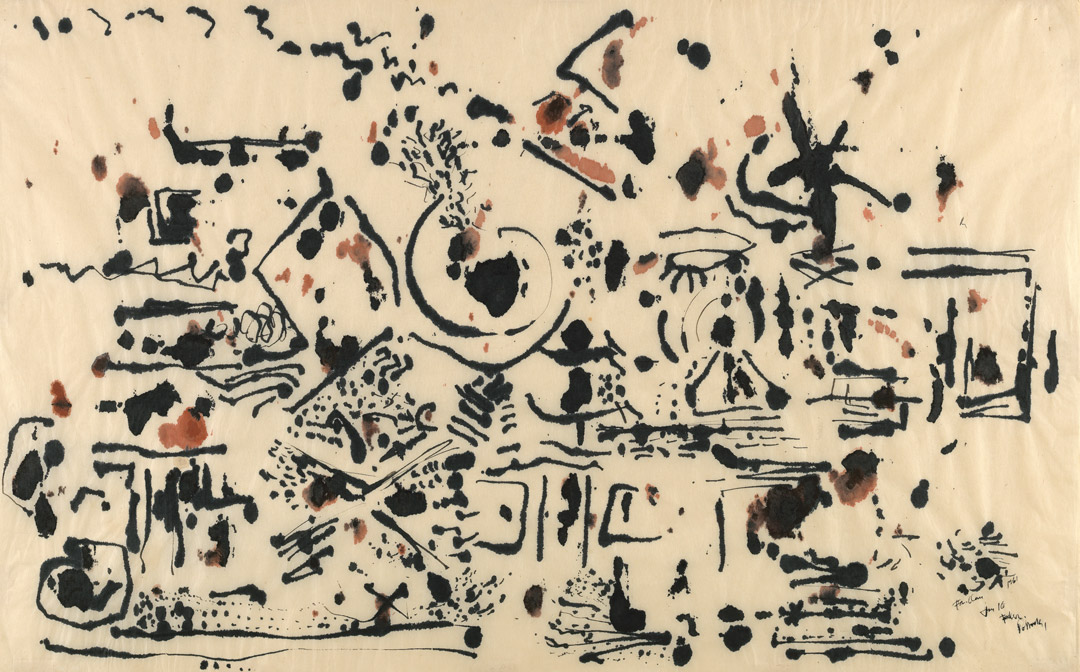

Jackson Pollock, Untitled, 1951

Acquired March 29, 1974

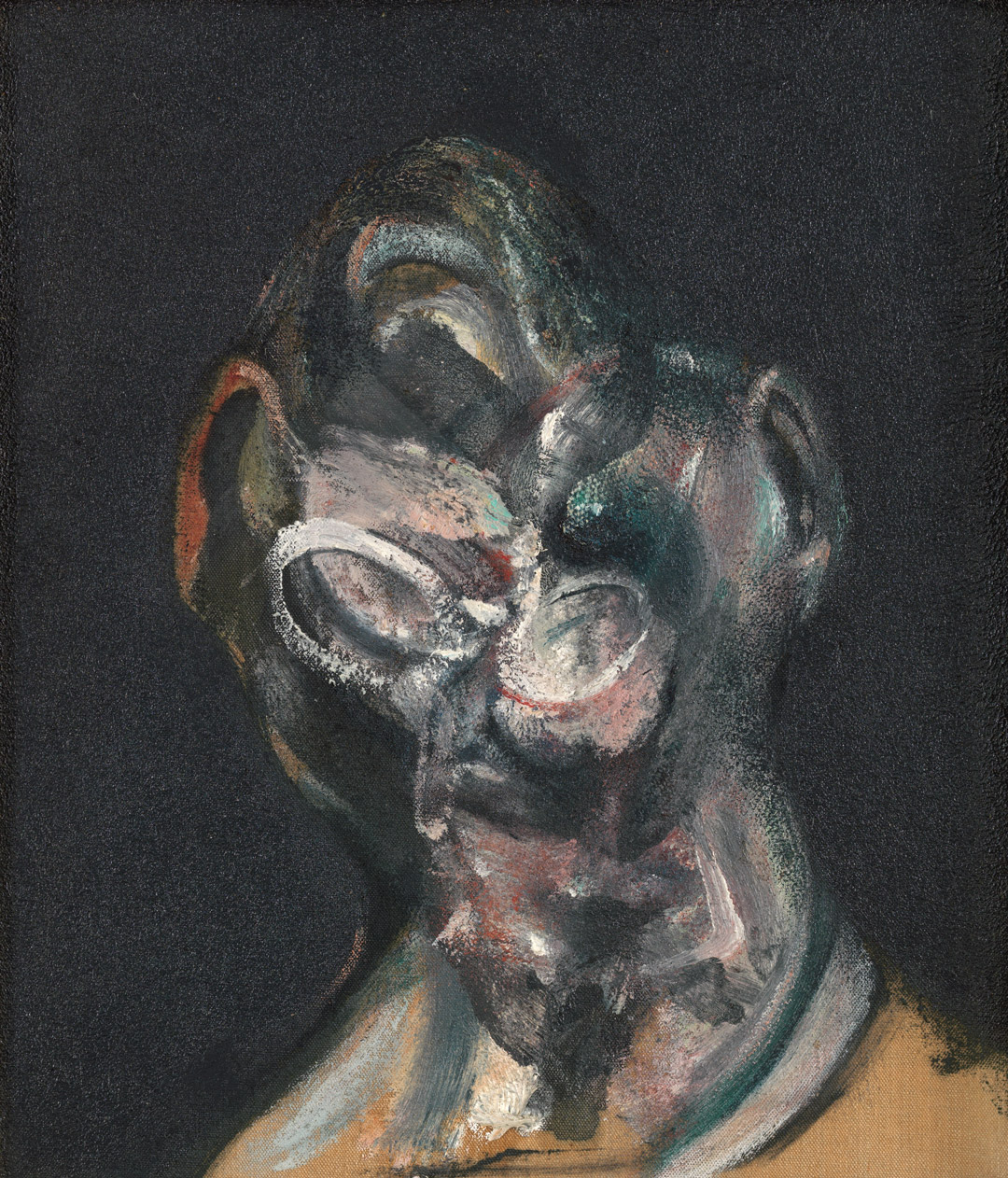

Francis Bacon, Portrait of Man with Glasses I, 1963

Acquired October 24, 1974

Alberto Giacometti, Femme de Venise II, 1956

Acquired January 2, 1975

Robert Motherwell, Irish Elegy, 1965

Acquired November 7, 1975

Francis Bacon, Study for a Portrait, 1967

Acquired November 20, 1976

Willem de Kooning, Town Square, 1948

Acquired December 6, 1976

Joan Mitchell, The Sink, 1956

Acquired September 12, 1977

David Smith, Cubi XXV, 1965

Acquired February 22, 1978

Philip Guston, To B.W.T., 1952

Acquired February 14, 1979

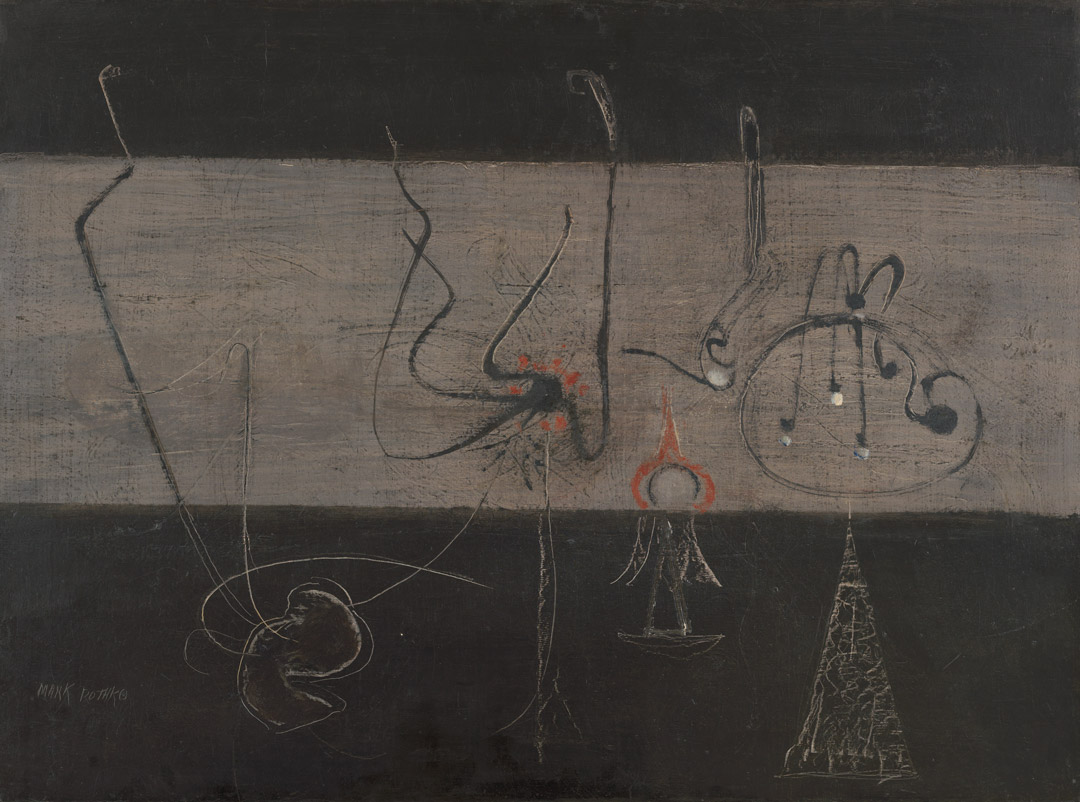

Mark Rothko, Untitled, ca.1945

Acquired November 12, 1980

Lee Krasner, Night Watch, 1960

Acquired November 19, 1981

Philip Guston, The Painter, 1976

Acquired February 1, 1982