The Sink

1956

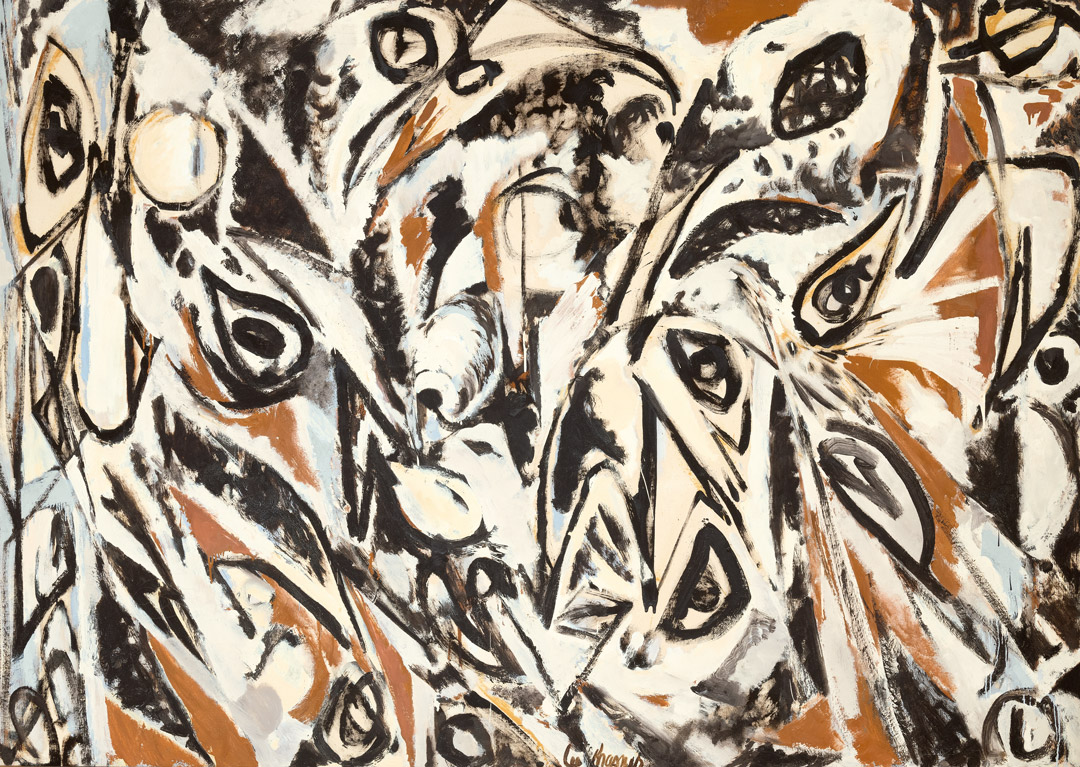

Joan Mitchell

American (1925–1992), oil on canvas, 54 5/8 × 111 3/4 in. (138.7 × 283.9 cm). Seattle Art Museum, Gift of the Friday Foundation in honor of Richard E. Lang and Jane Lang Davis, 2020.14.15. Photo by Spike Mafford / Zocalo Studios. Courtesy of Friday Foundation. © 2021 Estate of Joan Mitchell.

The Sink

Amy Rahn

Joan Mitchell’s 1956 painting The Sink,1 a gestural abstract painting more than nine feet across, rotates around a turbulent center in currents of ivory-gray-white amid a hail of precisely tuned yellow, pale green, and aqua flashes. Painted in a time of heady artistic success and personal transition for Mitchell, The Sink “condenses and concentrates” these turnings, to borrow Yves Michaud’s phrase, delivering the gyre of Mitchell’s mid-1950s, still roiling, into our present.

Mitchell, an American painter born and raised in Chicago, spent her formative years as an artist among the New York School of the 1950s. She painted consistently—and often monumentally—from the late 1940s until her death, a lifetime of sustained painterly achievement that is both characteristic of her generation of New York School painters and singular in its power, scale, ambition, and continuity. Arriving in New York in 1950 after a year in France on a painting fellowship, she admired the works of Willem de Kooning and Franz Kline and sought them out in their studios. Within the then-small world of downtown New York, she quickly became an integral participant in the intense culture of making paintings, talking about painting, and socializing around painting in studios, panel discussions, art galleries, and bars (fig. 1). Later in the decade, Mitchell’s relationships in these social circles became fraught, and she removed herself to Paris for the summer—a decision that would shape the rest of her life. As Mitchell explained to an interviewer, she went to Paris in 1955 to “get away from . . . personal things,” but then, “of course ran into other personal things.”2

“A true and accurate painting condenses and concentrates aspects of things . . . without coordinating them, without storytelling. It tells of their accretion, their accumulation.”

Yves Michaud

Establishing a new life in Paris meant acclimating to and rediscovering the city; it also meant searching for studio space in which to work. Mitchell maintained her painterly momentum while moving between five different studios between May and October 1955. By the following summer, she had secured the American painter Paul Jenkins’s studio on the rue Decrès while he borrowed hers on St. Mark’s Place in New York; the early fall found her working in a studio on the rue Daguerre (fig. 2) before returning to painting in New York in the late fall and winter of 1956–57. Engaged in an affair with the artist Jean-Paul Riopelle and integrated with an artistic community that included Shirley Jaffe, Sam Francis, and Alberto Giacometti, Mitchell painted intensively in two places and in two social and artistic circles for four years before moving to Paris permanently in 1959. The Sink emerged from this transitional and transnational period.

Near The Sink’s center, viscous white reaches vertically to the top and bottom edges of the painting like an axis; beside it, a mass of shorter strokes of vibrant red, spring green, white, and pink simultaneously build to a point and shatter laterally, pushing into the more broadly painted white areas near the canvas’s center and right. Intense bursts of color and expanses of white press and balance against one another, making the whole seem to rotate, a slow hurricane with a red-white curlicue near the painting’s center as its eye (fig. 3). This inner knot spins the composition toward the painting’s upper surface and the canvas taut below it, even as it pivots laterally around its core. In other words, the painting rotates within itself in two directions, swirling around its center while cycling toward and away from the viewer. The Sink’s interconnected turns, built of thousands of painterly decisions in color and stroke that seem to move at different speeds, form a visual choreography over which the painting’s title hangs like a question.

“The Sink” could reference a less-charged rotation than Mitchell’s passages from Paris to New York and back—namely, the everyday whorl of an ordinary studio sink. The painting’s rushing quality and rotational composition might even invite such an interpretation. Yet even the title of this dynamic work refuses to stay still: the painting has been referred to as both Sink and The Sink, refusing to resolve into the grammatical clarity of a verb or a noun.3 Indeed, Mitchell’s titles can be an unreliable guide to any imagined imagery they might contain, and even a misdirection. For example, an art dealer once claimed The Sink referred to “a low depression of land filled with water,” supposedly located near a studio of Mitchell’s near Chicago’s Lincoln Park.4 Since Mitchell did not have a studio in Chicago after moving to New York in the late 1940s, that referent seems unlikely at best.

The desire to map Mitchell’s abstraction back onto nameable referents, though, is understandable; a viewer would certainly not be alone in looking for something in her paintings, whether a studio fixture or topographical feature. Mitchell worked from memory and feeling, and feelings about memory, and surely those memories and feelings were suffused with the forms and figures of the world. Still, Mitchell’s titles do not so much correspond to their subject matter as ride over the surface of her works, adding a linguistic experience likely associated with a private memory of Mitchell’s to a fusion of inner- and outer-world fragments, transformed into paint. When, for example, the critic Irving Sandler narrated the painting of two of Mitchell’s canvases for his watershed 1957 Art News article “Joan Mitchell Paints a Picture,” he figured her process of painting as discovering and losing a memory-image in the work. He wrote of Mitchell’s George Went Swimming at Barnes Hole, but It Got Too Cold that the painting began with a memory of her poodle Georges du Soleil swimming, but the painting eventually got too white, too bleak, “too cold.”5 Sandler quoted Mitchell, “If a painting comes from [my personal meanings/references] then they don’t matter. Other people don’t have to see what I do in my work.”6 Concluding with Mitchell seeing her paintings as paintings, as new works transformed from personal recollections, Sandler wrote: “the vital matter is transferred to works in progress.”7

The artist’s titles might have also served a practical purpose. Before 1955, Mitchell often titled major paintings Untitled. From the mid-1950s onward, she titled her works more lucidly, assigning titles like The Sink. Since, at this point, she was sending her paintings from Paris to New York and tracking payments and ownership for her works sold through the Stable Gallery, Mitchell might have changed her titling practices to ease the logistical headaches of her transatlantic career. “The Sink” might thus summon an external referent, an impression consonant with the work’s final form, a name cast over the painting to track its passage between places, or all three. Reading titles as a potential sign of Mitchell’s acuity in the management of her career resonates with The Sink’s originary moment in the mid-1950s—a moment of transition for Mitchell as her professional acclaim mounted. As she and her works flew between continents, her career accelerated.

These were years of critical celebration and institutional sanction. Mitchell’s March 1955 exhibition was named one of the year’s best by Art News, alongside those by Mark Rothko and Ad Reinhardt, making her the youngest artist so honored that year.8 Mitchell had four solo exhibitions at the Stable Gallery between 1953 and 1958 while also showing her work nationally and internationally, often in exhibitions designed to demonstrate what was most “current” in American art. Her inclusion in a 1957 exhibition at the Jewish Museum, Artists of the New York School: Second Generation, marked the esteem of insider critics and other artists,9 and the Whitney Museum of American Art acquired her painting Hemlock in 1958. That same year, her City Landscape appeared in the Society for Contemporary American Art annual exhibition at the Art Institute of Chicago, which subsequently purchased the work for its collection. Mitchell was also selected for the Venice Biennale in 1958, and in 1959 her work appeared in the Corcoran and São Paulo Biennials as well as the landmark exhibition documenta II.10 If Mitchell had begun the 1950s as a young artist seeking out the lions of the downtown painting scene, she closed the decade as an established artist with her own national and international reputation as an exemplar of the New York School.

Critics saw Mitchell’s works as capturing the energy of their moment. In his 1957 review of Mitchell’s Stable Gallery exhibition, which included The Sink, Irving Sandler wrote, “The love for painting which pulses through these canvases engulfs the viewer. This show should be seen in the morning, for it can animate the entire day.”11 Mitchell’s paintings radiated the energy of their making, “animating” the viewer’s lived experience. The French critic Pierre Schneider used the metaphor of natural and electric light to allude to Mitchell’s work across geographic contexts as a source of strength. In remarks made during the 1961 Salon de mai, Schneider transposed this inner/outer question of representation to the light itself, describing Mitchell’s 1960 painting Whaler as hybridizing the “electric” light of (German-then-American) Expressionist painting with the “natural” light of (French) Impressionist painting, concluding evocatively: “A painting by Joan Mitchell seems to me in a strangely hybrid zone—one has the impression of an electric bulb in broad daylight.”12 Schneider conceived the conditions of plein-air and studio painting as echoing outer and inner worlds. Electric in daylight, American in France, Mitchell’s paintings transformed her in-between position into a strength.

The Sink, a “condensed” and “concentrated” accumulation of time and experience in marks made during a pivotal moment in the artist’s life, knots her past and our present moment of emergence and possibility in its tense coiling. Painted during Mitchell’s own productive period of restless transition in the mid-1950s, the slippery riddle of The Sink draws us into its dislocations and revelations, a whorl that resonates with its time in Mitchell’s life and with our own complex moment, refusing to resolve into a single decodable meaning. The painting’s interior turns amid a rushing torrent in which we might experience the tension and possibility of the threshold, the incandescent in-between. Here it is, vital, burning in daylight.

Notes

Amy Rahn is an assistant professor of art history at the University of Maine at Augusta, where she is director of the Charles Danforth Gallery. She authored an essay for the recent Joan Mitchell retrospective exhibition catalogue (Yale University Press, 2021) and wrote the first English language dissertation on Mitchell.

Notes

Epigraph: Yves Michaud, “Chords,” in Joan Mitchell: Peintures 1986 et 1987, RIVER, LILLE, CHORD (Paris: Galerie Jean Fournier Éditions, 1987), 61.

1. This painting has alternately been titled both Sink and The Sink.

2. Joan Mitchell, Oral history interview with Dorothy Gees Seckler, May 21, 1965, Dorothy Gees Seckler Collection of Sound Recordings Relating to Art and Artists, 1962–1976, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC. Author’s transcription.

3. In the Stable Gallery records, for example, the painting is frequently titled “Sink” in inventories of Mitchell’s works—as it is, notably, in a September 9, 1960, letter from Walter Hopps of the Ferus Gallery to Eleanor Ward of the Stable Gallery with news of the painting’s sale. Stable Gallery Records, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. By the time the Langs purchased the painting in 1977, it had become “The Sink.” See Adler Gallery correspondence, September 2 and 12, 1977.

4. Abe Adler to Richard Lang, September 2, 1977, Friday Foundation archives.

5. Irving Sandler, “Joan Mitchell Paints a Picture,” Art News 56, no. 6 (October 1957): 70.

6. Sandler, “Joan Mitchell Paints a Picture,” 70.

7. Sandler, “Joan Mitchell Paints a Picture,” 70.

8. Alfred Frankfurter, “The Year’s Best: 1955,” Art News 54, no. 9 (January 1956): 10.

9. This exhibition was selected, in part, by Meyer Schapiro at the Jewish Museum in 1957, and its catalogue includes an essay by Leo Steinberg.

10. documenta II (1959) was the second installment of an international art exhibition first held in Kassel, Germany, in 1955, as an effort to reconnect Germany with the wider world of the arts after World War II. documenta II, in which Mitchell participated, proposed abstract art as a language that could unite Europe. This explicitly internationalist (though primarily European and American) exhibition included 336 artists, among them first-generation Abstract Expressionist artists like Willem de Kooning and Jackson Pollock and second-generation Abstract Expressionists such as Helen Frankenthaler and Grace Hartigan. Held every five years for one hundred days, documenta continues to be a highly anticipated event. See “Retrospective: documenta 2, July 11–October 11, 1959, Art after 1945; International Exhibition,” documenta: retrospective website, accessed November 2, 2020, http://www.documenta.de/en/retrospective/ii_documenta#.

11. Irving Sandler, “Young Moderns and Modern Masters: Joan Mitchell (Stable),” Art News 56, no. 1 (March 1957): 64.

12. Pierre Schneider, in Jacques Putman, Jean-François Revel, Pierre Schneider, and Albert Schultze-Vellinghausen, “Au Salon de mai,” L’Oeil, June 1961, 53. Translation by the author.

Explore the Collection

Sort by Chronology

Sort by Artist

Sort by Author

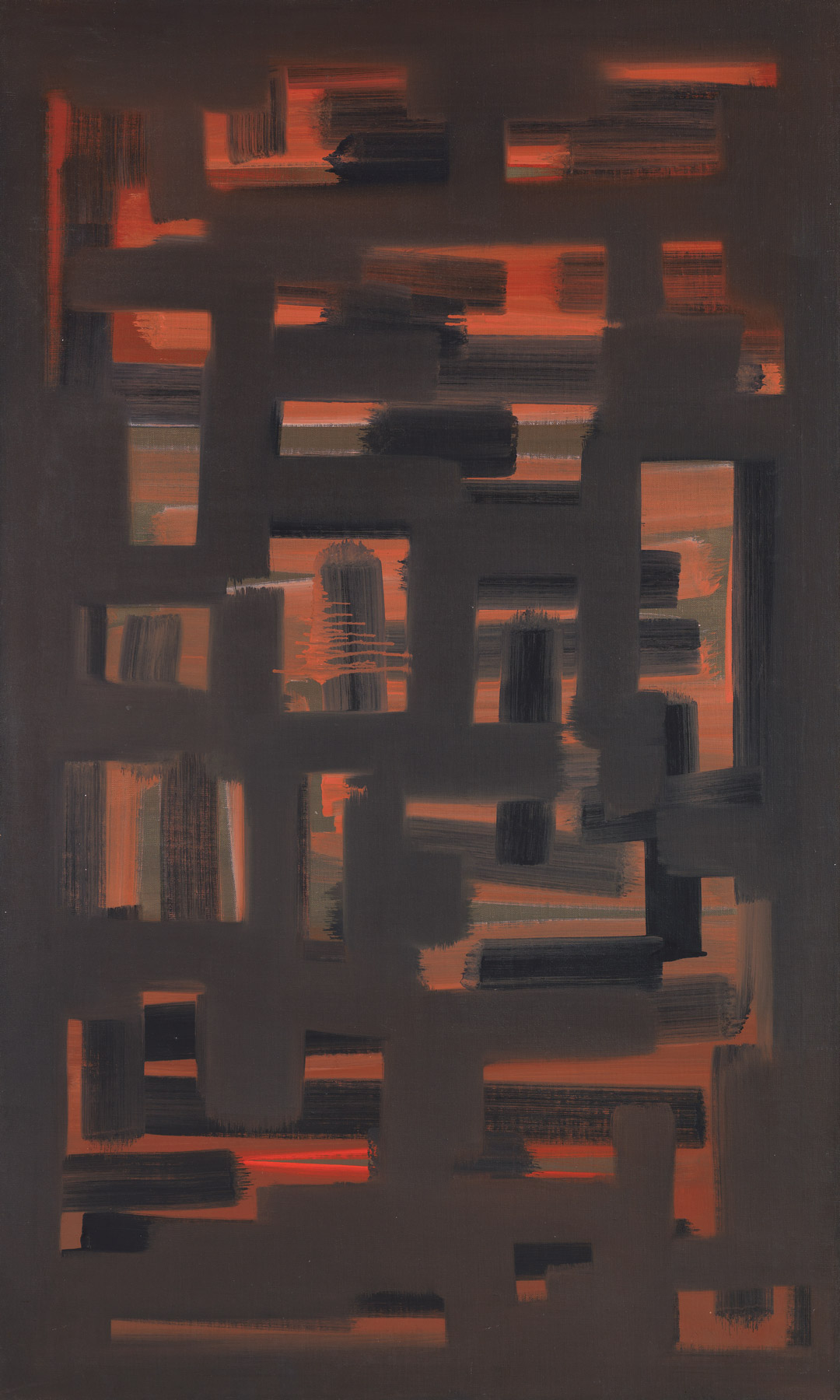

Franz Kline, Painting No. 11, 1951

Acquired November 13, 1970

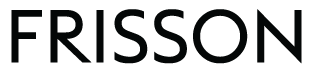

Mark Rothko, Untitled, 1963

Acquired May 18, 1972

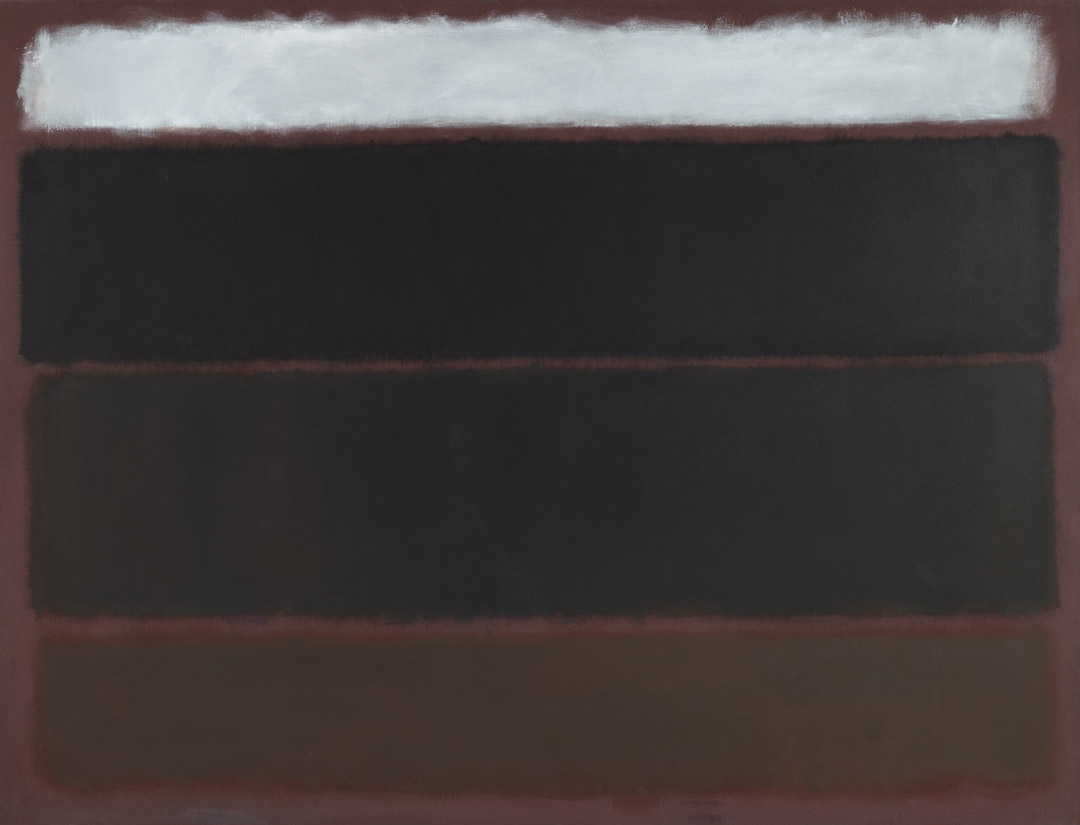

Robert Motherwell, Before the Day, 1972

Acquired October 12, 1972

Adolph Gottlieb, Crimson Spinning #2, 1959

Acquired December 11, 1972

Helen Frankenthaler, Dawn Shapes, 1967

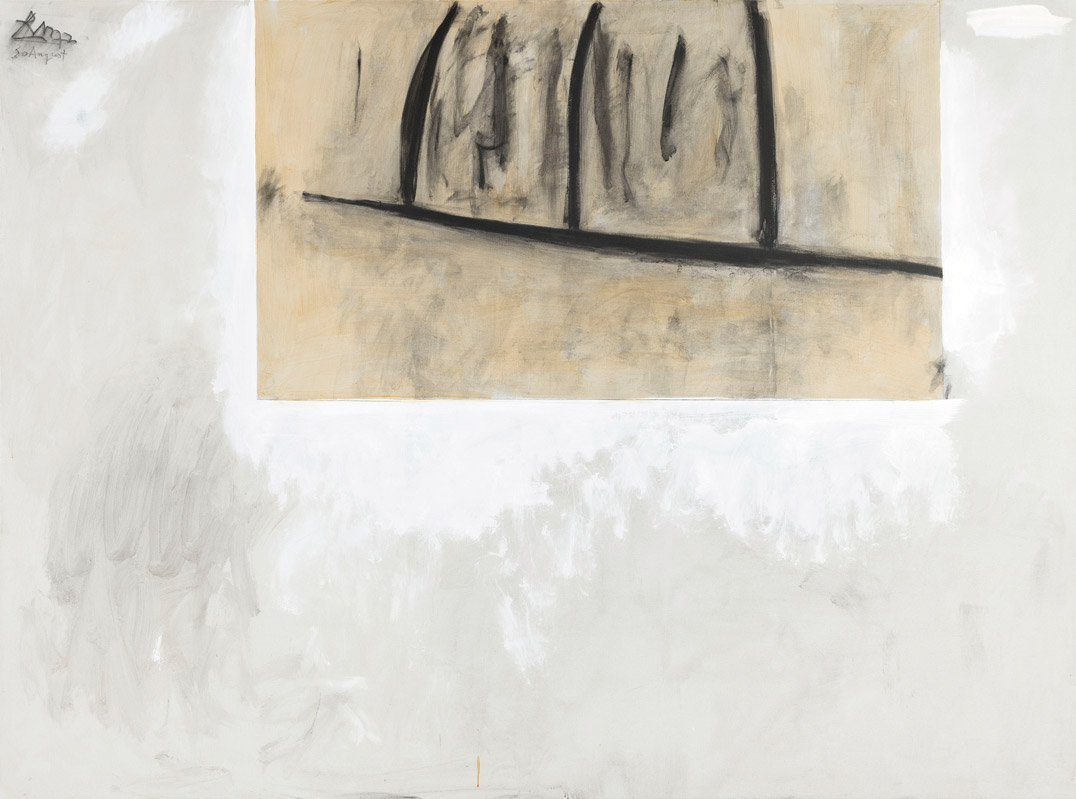

Acquired April 26, 1973

Clyfford Still, PH-338, 1949

Acquired November 10, 1973

Ad Reinhardt, Painting, 1950, 1950

Acquired January 8, 1974

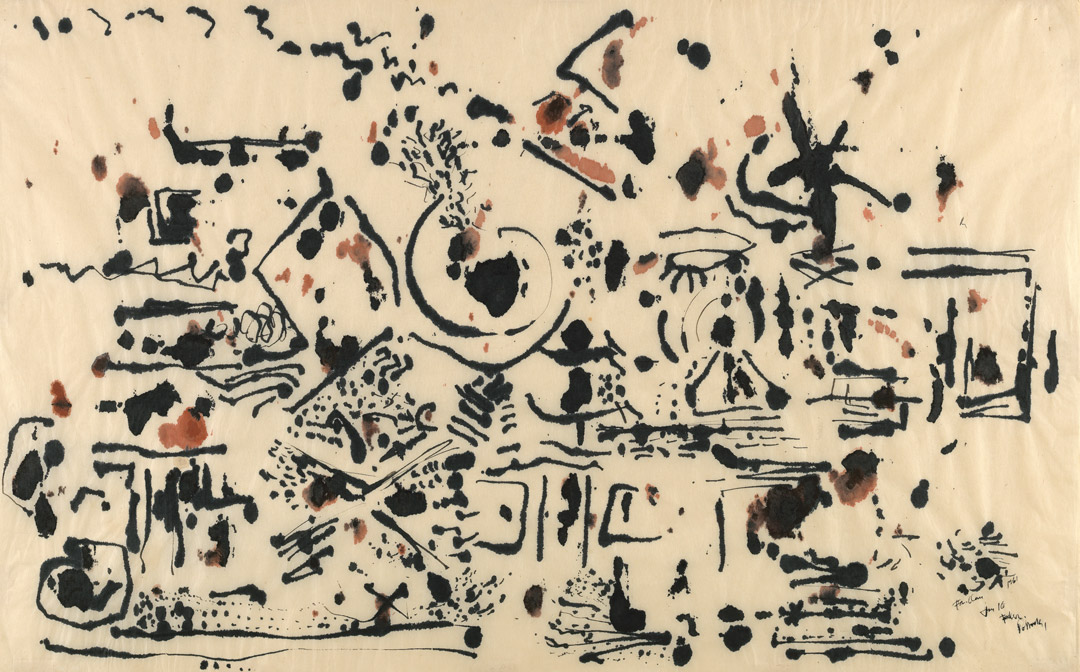

Jackson Pollock, Untitled, 1951

Acquired March 29, 1974

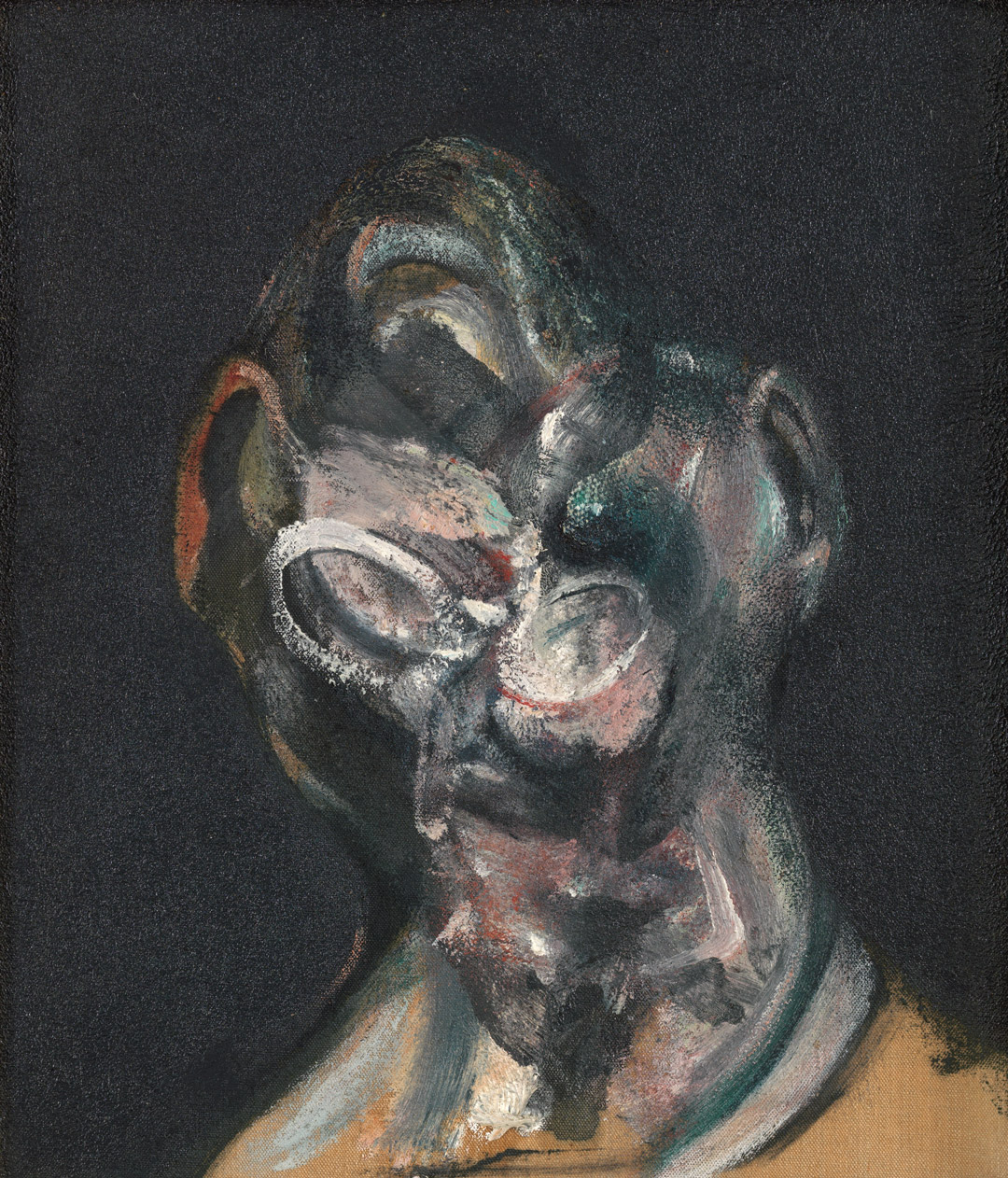

Francis Bacon, Portrait of Man with Glasses I, 1963

Acquired October 24, 1974

Alberto Giacometti, Femme de Venise II, 1956

Acquired January 2, 1975

Robert Motherwell, Irish Elegy, 1965

Acquired November 7, 1975

Francis Bacon, Study for a Portrait, 1967

Acquired November 20, 1976

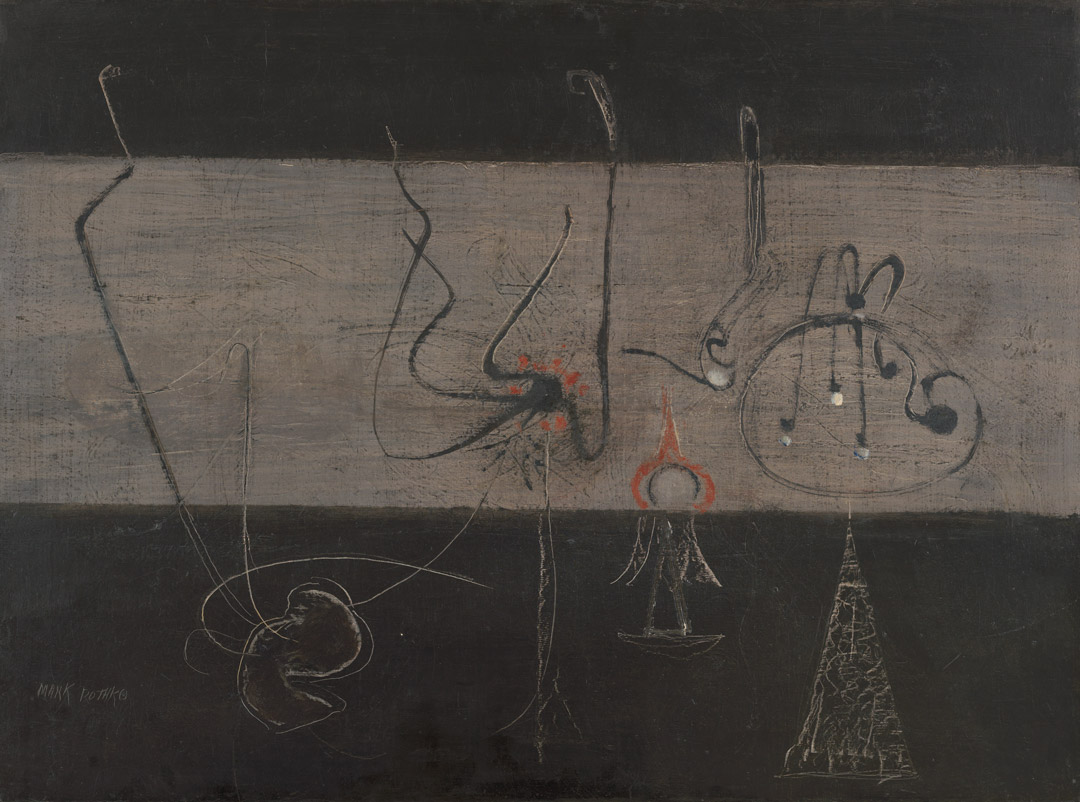

Willem de Kooning, Town Square, 1948

Acquired December 6, 1976

Joan Mitchell, The Sink, 1956

Acquired September 12, 1977

David Smith, Cubi XXV, 1965

Acquired February 22, 1978

Philip Guston, To B.W.T., 1952

Acquired February 14, 1979

Mark Rothko, Untitled, ca.1945

Acquired November 12, 1980

Lee Krasner, Night Watch, 1960

Acquired November 19, 1981

Philip Guston, The Painter, 1976

Acquired February 1, 1982