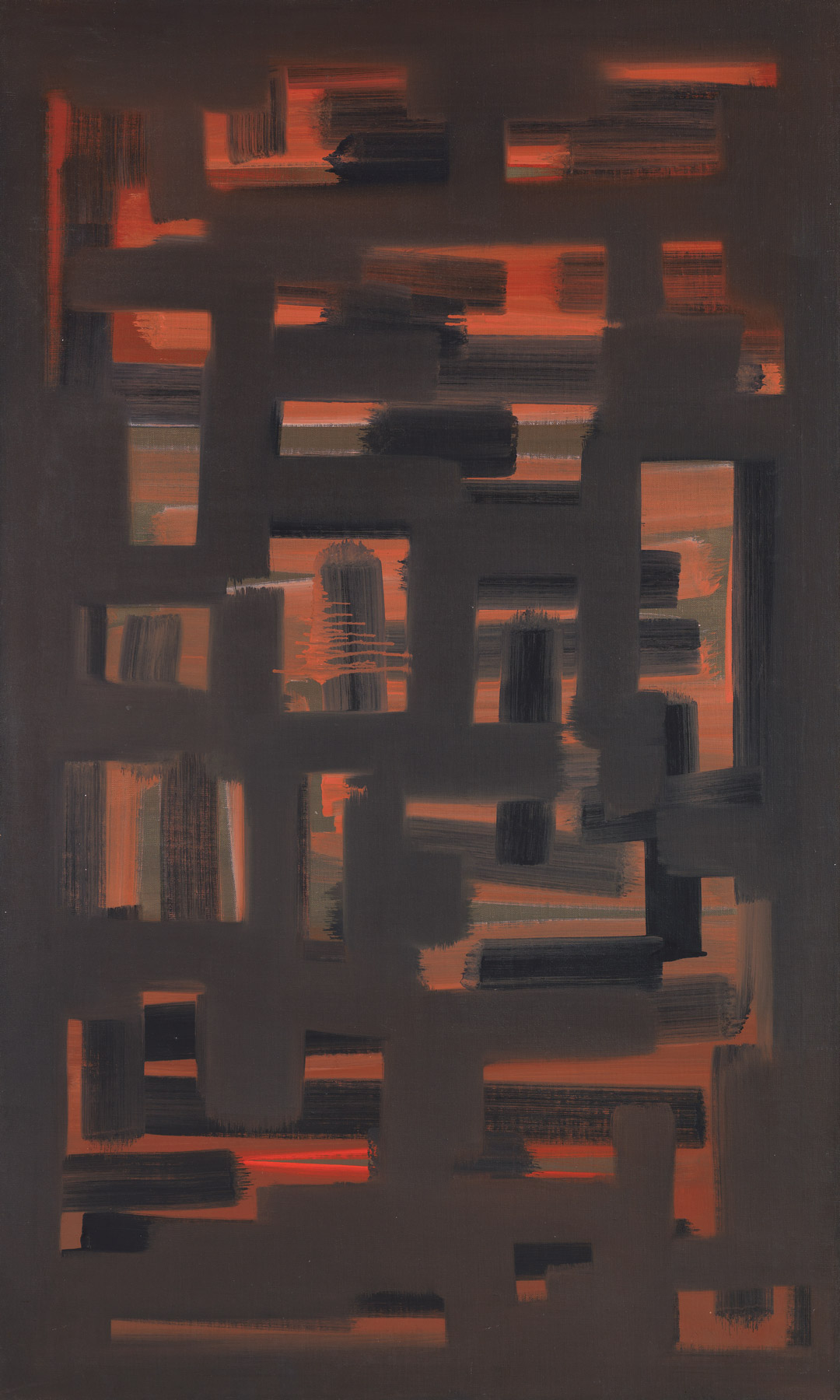

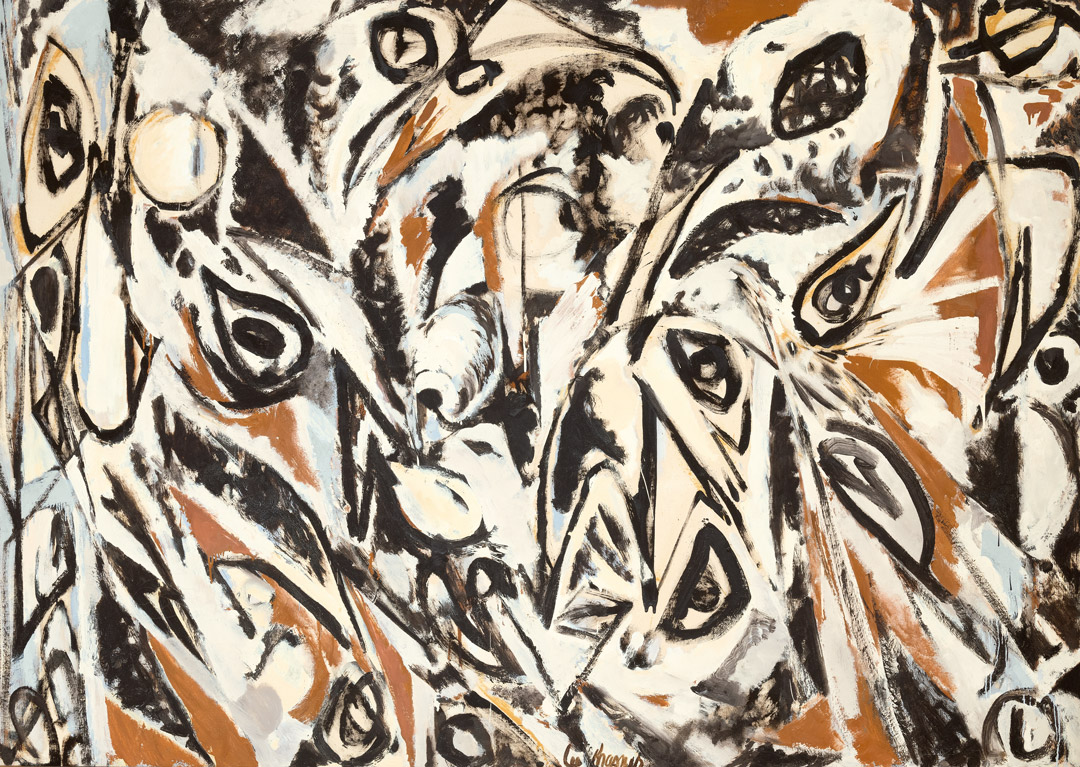

Irish Elegy

1965

Robert Motherwell

American (1915–1991), acrylic on canvas, 69 1/2 × 83 3/4 in. (176.5 × 212.8 cm). Seattle Art Museum, Gift of the Friday Foundation in honor of Richard E. Lang and Jane Lang Davis, 2020.14.1. Photo by Spike Mafford / Zocalo Studios. Courtesy of Friday Foundation. © 2021 The Robert Motherwell Estate / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Irish Elegy

Jack Flam

Robert Motherwell’s Irish Elegy, which was painted in early 1965, is a monumental and austere painting, straightforward in structure but charged with complex associations and overtones.1 It is one of the artist’s most pared-down Elegy paintings: the basic composition contains a single black oval set against two dark vertical forms, rather than the multiple ovals and vertical bars that are typical of the series. The color is also unique among the Elegies, most of which are painted in starkly contrasting areas of black and white, which the artist associated with the duality between life and death.2 In Irish Elegy, the black oval is set against a gray ground, and the black verticals that press against it are enwreathed by sinuous areas of green. A bold-blue rectangle is painted over the right-hand vertical form, adding a dissonant geometric element to the supple forms in the rest of the composition. The only white passage in this picture is a thin, unevenly painted line that descends from the top left of the painting like a bolt of electric current, creating an unexpected laceration in the large black form it traverses.

This painting, perhaps more than any of the other large Elegies, is intensely intimate and somber. Composed in a close range of tonal values rather than what Motherwell called the “éclat” of bright whites set against blacks, it radiates the kind of pensive melancholy that is inherent in minor-key music. The sense of intimacy, solemnity, and self-containment is enhanced by the directional thrust of the two oblong vertical forms from right to left—rather than left to right, as in almost all the other Elegy paintings, which lends them an air of lightness and movement. Since our Western way of reading a picture is, like reading text, from left to right, the directional thrusts of the vertical forms in this painting instead create a certain amount of resistance to the eye, adding to the somber, bounded feel of the composition as a whole. Although Motherwell has stated that his Elegy paintings were “for the most part, public statements,”3 this painting is an exceptionally private and personal one.

Irish Elegy is unique in another way: it is the only painting in Motherwell’s celebrated Elegy series that refers to a place outside of Spain.4 And yet the impulses behind this painting are very similar to those that were at the root of the artist’s Elegies to the Spanish Republic: a complex amalgam of literature, politics, and a deep sense of tragedy.

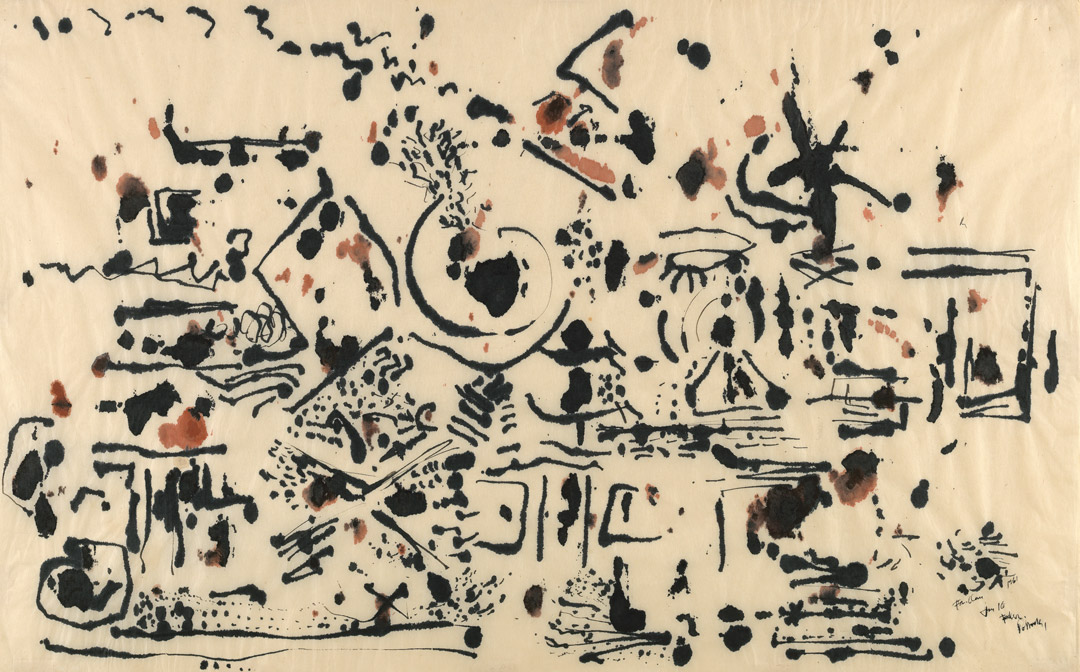

Motherwell created the very first Elegy-like composition during the summer of 1948 in a brush-and-ink drawing made to illuminate the concluding lines of a poem by Harold Rosenberg called “A Bird for Every Bird.” Text and image were supposed to appear in the never-published second issue of the art and literature revue possibilities, which Motherwell was coediting with Rosenberg. In the fall, Motherwell was inspired to return to the imagery of that drawing and use its compositional format of ovals set against vertical bars as the point of departure for his first painting of the Elegy motif, At Five in the Afternoon (1948–49, fig. 1). That painting takes its title from the refrain of Federico García Lorca’s poem “Llanto por Ignacio Sánchez Mejías,” which is an elegy for a great matador (himself also a poet) who was fatally gored in the bullring “at exactly five in the afternoon.”

Between 1949 and the beginning of 1965, Motherwell created over one hundred paintings in the series Elegies to the Spanish Republic, meant to commemorate the overthrow of the Spanish Republican government by fascists, which Motherwell considered one of the great political tragedies of his time. But the paintings were also meant to transcend any specific political situation and convey a general sense of tragedy, what Motherwell described in 1950 as “funeral pictures, laments, dirges, elegies—barbaric and austere.”5 Although almost all the Elegy paintings were rendered primarily in black and white, some contained blocks of color, often used in an overtly symbolic way. The bright colors on the left side of Elegy to the Spanish Republic XXXIV (1953–54, fig. 2), for example, recall those of the flag of the Second Spanish Republic (1931–39).

The colors in Irish Elegy are also symbolically related to its nominal subject. Green is, of course, closely associated with Ireland, and Motherwell surely meant for this association to be clear. When the painting was shown at his 1965 retrospective exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, Time magazine reported that it “was so titled, says Robert Motherwell, whose ancestors hailed from Ireland, because the winding green lines convey a feeling of the old sod.”6 Moreover, green and blue are the colors of the flag of the City of Dublin (fig. 3), to which the blue rectangle in Irish Elegy appears to allude. Such indirect but firmly imbedded symbolic associations are typical of Motherwell’s works, which eschew direct or literal narrative but embrace the idea of expressing various aspects of their subject matter through complex and resonant networks of associations.

These associations, and the explicit title of Irish Elegy, lead one to ask: Why did Motherwell paint an Irish-themed Elegy at this particular time, in 1965?

Here, it is worth noting that Motherwell, who proudly referred to himself as “a Celt,”7 was a passionate admirer of the works of William Butler Yeats, whose centenary was celebrated in 1965, and especially of James Joyce, who inspired several of Motherwell’s works. Moreover, two of Motherwell’s closest friends in 1965 were of Irish descent—the sculptor David Smith and the poet Frank O’Hara—though neither of them appears to have been especially interested in Irish politics.

Irish politics, however, were very much in the air at the time. Although “the Troubles” in Northern Ireland between the Catholic Nationalists and Protestant Unionists are usually said to have started in 1968, the term was being used at least as early as 1964, a year when intense violence in Northern Ireland was reported by the US press.8 Motherwell’s interest in the Irish situation was given tangible expression in April 1964, when he finished his large painting Dublin 1916, with Black and Tan (Empire State Plaza Art Collection), which alluded directly to the Irish Republican rebellion during Easter week 1916, as well as to Yeats’s celebrated poem “Easter 1916,” and to the “Black and Tan” British troops who fought against the Republicans during the subsequent Irish War of Independence.

But another, very specific event seems to have served as a major inspiration for Irish Elegy: the death of President John F. Kennedy. This is something that Motherwell alluded to in a conversation with Walter Barker, who reviewed his 1965 retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art. Barker wrote that when asked about the titles of his paintings, “Motherwell explained that they exist on a number of associative levels. ‘Irish Elegy,’ for example, relates to his maternal ancestors, the Irish famine, Yeats, Joyce, whose work he loves, and the Kennedy family whom he admires.”9 It is not surprising that Motherwell felt a particular affinity with John F. Kennedy, who was only two years his junior, shared similar political views, and had brought a vigorous feeling for high culture to the White House.

Motherwell painted Irish Elegy only fifteen months after Kennedy was assassinated, and at a time when Kennedy’s legacy was receiving a good deal of media attention. Toward the end of May 1964, organizers announced that a John F. Kennedy memorial garden would be created near the “Kennedy ancestral home” in Ireland, “financed by Irish-American societies.”10 On May 29, which would have been Kennedy’s 47th birthday, Irish president Eamon de Valera laid a wreath on Kennedy’s grave and attended a “solemn pontifical requiem mass” for him at the Shrine of the Immaculate Conception in Washington, DC. Both were widely covered in the press.11 These tributes to Kennedy coincided with a number of events related to James Joyce. In February 1964, the visit to New York by Joyce’s sister May (Mary Kathleen) Joyce Monaghan received a good deal of attention.12 And only a few months later, in May 1964, the James Joyce Society was formed, with the initial aim of placing a plaque at Joyce’s birthplace.13

Kennedy and Ireland were also on Motherwell’s mind at the beginning of 1965 for another reason. In December 1963, just a week after Kennedy was assassinated, the US General Services Administration had announced that the federal office building that was to be built in Boston would be named after the late president. The architects for the building, who had been appointed in January 1961, were Walter Gropius and his firm, the Architects Collaborative, working with the assistance of the Boston architect Samuel Glaser. Motherwell had worked with Gropius and the Architects Collaborative as far back as 1950, when he had been commissioned to paint a mural for a Gropius-designed junior high school in Attleboro, Massachusetts, and the two men had a cordial relationship. Gropius had planned to commission art for the Boston building since the beginning of the project, and he and Motherwell appear to have discussed the possibility of his painting a large mural for the main lobby of the building sometime in late 1964 or early 1965.

Thus, at the time he painted Irish Elegy, Motherwell was thinking about a mural commission for the lobby of the John F. Kennedy Federal Building; and only a few months after he finished Irish Elegy, he began to work on the large mural painting that would come to be known as the New England Elegy—although the liquid forms in that painting look nothing like the established Elegy format of ovals played against oblong verticals. Significantly, Motherwell had originally intended to call the mural painting for the Kennedy building Tragic Elegy—a title that would have carried a great emotional charge, but which was apparently deemed inappropriate for a federal office building.14

Motherwell’s deep feeling for his Irish Elegy is reflected in its exhibition history. It was shown for the first time at an exhibition called Critics’ Choice: Art since World War II, which opened on March 31, 1965, at the Providence Art Club, in Rhode Island, and was curated by three of the leading critics of the time, Thomas B. Hess, Hilton Kramer, and Harold Rosenberg.15 The three prominent critics had been asked to vote on whom to include as “Artists of Outstanding Significance after World War II,” with each to be represented by a single work. Motherwell’s recently painted Irish Elegy proudly represented him alongside works by colleagues such as Franz Kline, Willem de Kooning, Barnett Newman, Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, and David Smith, as well as older European artists including Balthus, Jean Dubuffet, Alberto Giacometti, and Henry Moore. Irish Elegy was also included in Motherwell’s retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in the fall of 1965, and in his 1983 retrospective at the Albright-Knox Art Gallery; both were exhibitions for which Motherwell himself chose most of the works.

If Irish Elegy was, in effect, an elegy to John F. Kennedy, one might ask why Motherwell gave the painting such a general title. This goes to the heart of Motherwell’s aesthetic philosophy. Throughout his career, Motherwell avoided literal narrative and followed the principle of painting not the subject but his feelings for the subject. And in this instance, he must have felt that naming the painting for Kennedy would have been unseemly and would have undercut the resonance of what he hoped would be a universal image. Instead, by investing the work with multilayered Irish references, he was able to open it up to a deeper and broader range of feelings and meanings, very much in accordance with his belief that works of art accumulate meaning through networks of associations.

“I take an elegy to be a funeral lamentation or funeral song for something one cared about,” Motherwell stated in the catalogue for his 1963 exhibition at Smith College.16 And, life being what it is, an Elegy for one person who was “cared about” can eventually come to serve as an Elegy for others. Indeed, only a few months after Motherwell painted Irish Elegy, David Smith was killed in a car crash, and just a year after that, Frank O’Hara also died in an accident. The broad title of Irish Elegy enabled the painting to pay tribute to those the artist cared about, not only in the past but in the future, just as the intensity of its imagery encompassed generations of tragedies from the Great Famine to the Troubles.

Author

Jack Flam is president and CEO of the Dedalus Foundation and distinguished professor emeritus of art history at the City University of New York. He is coauthor of Robert Motherwell Paintings and Collages: A Catalogue Raisonné, 1941–1991 (Yale University Press, 2012) and Robert Motherwell: 100 Years (Skira, 2015).

Notes

1 Irish Elegy was probably painted in late February, as suggested by entries in the artist’s 1965 datebook, now in the Dedalus Foundation Archives, where he notes receiving a shipment of canvas on February 11 and records all-day painting sessions on February 21, 22, and 27; the painting was included in a show at the Providence Art Club that opened on March 31.

2 “My Spanish Elegies are also free-association,” Motherwell stated in 1962. “Black is death, anxiety; white is life, éclat.” See Charles Chetham, “Robert Motherwell: A Conversation at Lunch,” in An Exhibition of the Work of Robert Motherwell (Northampton, MA: Smith College Museum of Art, 1963), n.p.

3 See Jack D. Flam, “With Robert Motherwell,” in Robert Motherwell, Jack D. Flam and Dore Ashton (Buffalo, NY: Albright-Knox Art Gallery; New York: Abbeville Press, 1983), 22.

4 Havana, 1951, has an Elegy-like composition but is not called an Elegy; New England Elegy, discussed below, does not follow at all the visual format of the Elegy series.

5 Robert Motherwell, quoted in Kootz Gallery, Motherwell: First Exhibition of Paintings in Three Years (New York: Samuel M. Kootz Gallery, 1950), n.p.

6 “Painting: Lochinvar’s Return,” Time, October 8, 1965, 85. Motherwell’s father was from a Scottish Protestant family; his mother’s background was Irish Catholic.

7 See Stephanie Terenzio, ed., The Collected Writings of Robert Motherwell (New York: Oxford University Press, 1991), 196, 203. Motherwell referred to himself as such many times in conversation with me.

8 See, for example, “Violence Erupts in Belfast over Removal of Irish Flag,” New York Times, October 2, 1964. Horace Reynolds, “Growing Up in Ireland,” published in the October 11, 1964, issue of the New York Times, speaks of “Ireland with its political and religious excesses, its Troubles and its Puritanism.” See also Tyrone Guthrie, “Close-Up of Ireland’s Basic Problem,” New York Times, January 19, 1962.

9 Walter Barker, “Painter of the Indomitable Gesture: Robert Motherwell Retrospective at the Modern,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, November 21, 1965.

10 “Ireland Will Get a Kennedy Garden,” New York Times, May 26, 1964.

11 “De Valera Lays Wreath on Kennedy’s Grave,” New York Times, May 30, 1964.

12 See Brian O’Doherty, “A Sister Recalls Joyce in Dublin: Mrs. Monaghan Is Here for Writer’s 82nd Anniversary,” New York Times, February 3, 1964.

13 The society was founded by Frederic H. Young, a professor at Montclair State College in New Jersey, who on his first trip to Ireland had been surprised to find that there was no plaque there. See New York Times, May 10, 1964.

14 In an April 20, 1966, letter to Gropius, Motherwell wrote, “I call the mural ‘Tragic Elegy,’” but acknowledged that the mural would be considered “far out” in relation to public taste (Walter Gropius Papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution). For details about the New England Elegy, see Jack Flam, Katy Rogers, and Tim Clifford, Robert Motherwell Paintings and Collages: A Catalogue Raisonné, 1941–1991, 3 vols. (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2012), 1:107–9, 2:205–7.

15 The rationale behind the exhibition, which was mounted in honor of the bicentennial of Brown University and ran from March 31 to April 24, 1965, is discussed in the catalogue, Critics’ Choice: Art since World War II. Artists Selected by Thomas B. Hess, Hilton Kramer and Harold Rosenberg (Providence, RI: Providence Art Club, 1965).

16 Robert Motherwell, in Chetham, “Robert Motherwell,” n.p., caption to Dawn Shapes.

Explore the Collection

Sort by Chronology

Sort by Artist

Sort by Author

Franz Kline, Painting No. 11, 1951

Acquired November 13, 1970

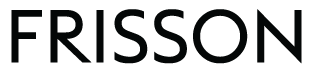

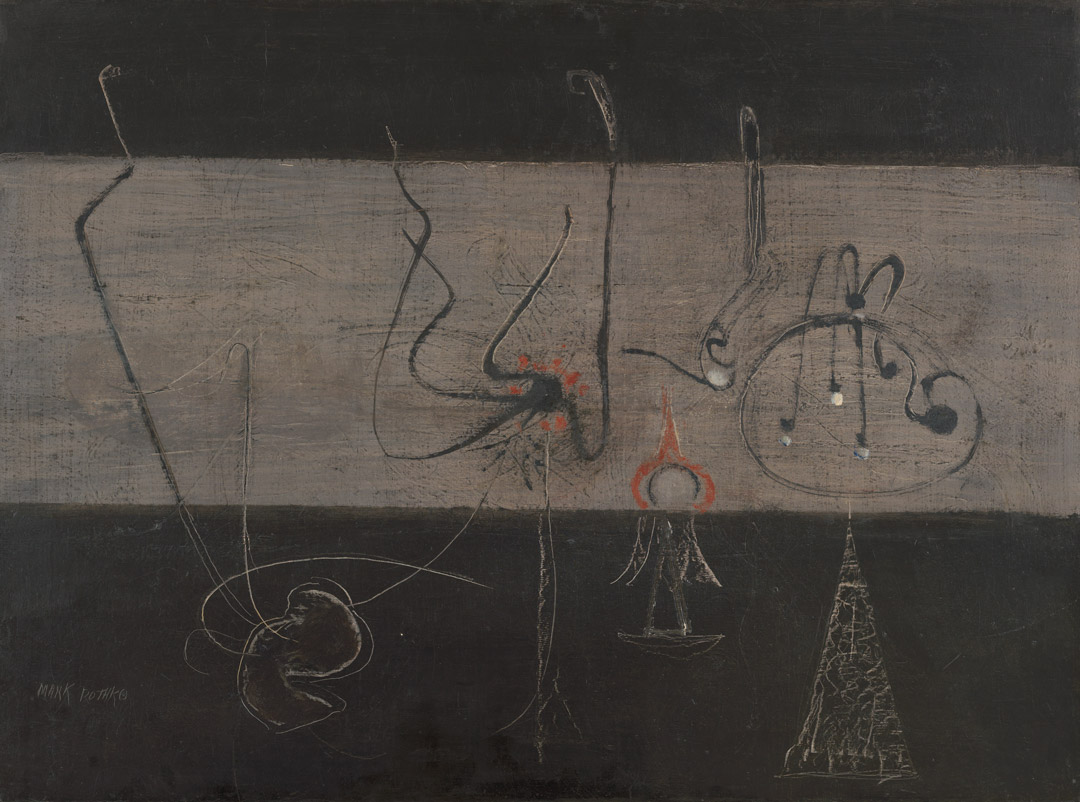

Mark Rothko, Untitled, 1963

Acquired May 18, 1972

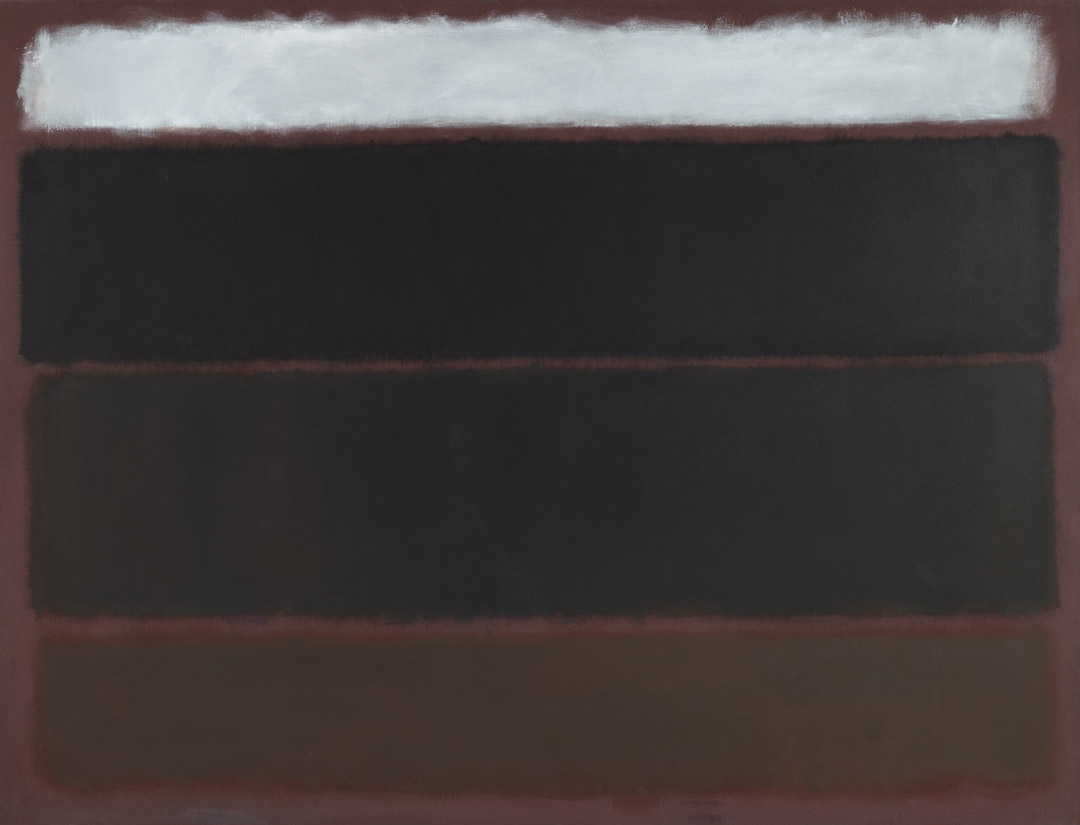

Robert Motherwell, Before the Day, 1972

Acquired October 12, 1972

Adolph Gottlieb, Crimson Spinning #2, 1959

Acquired December 11, 1972

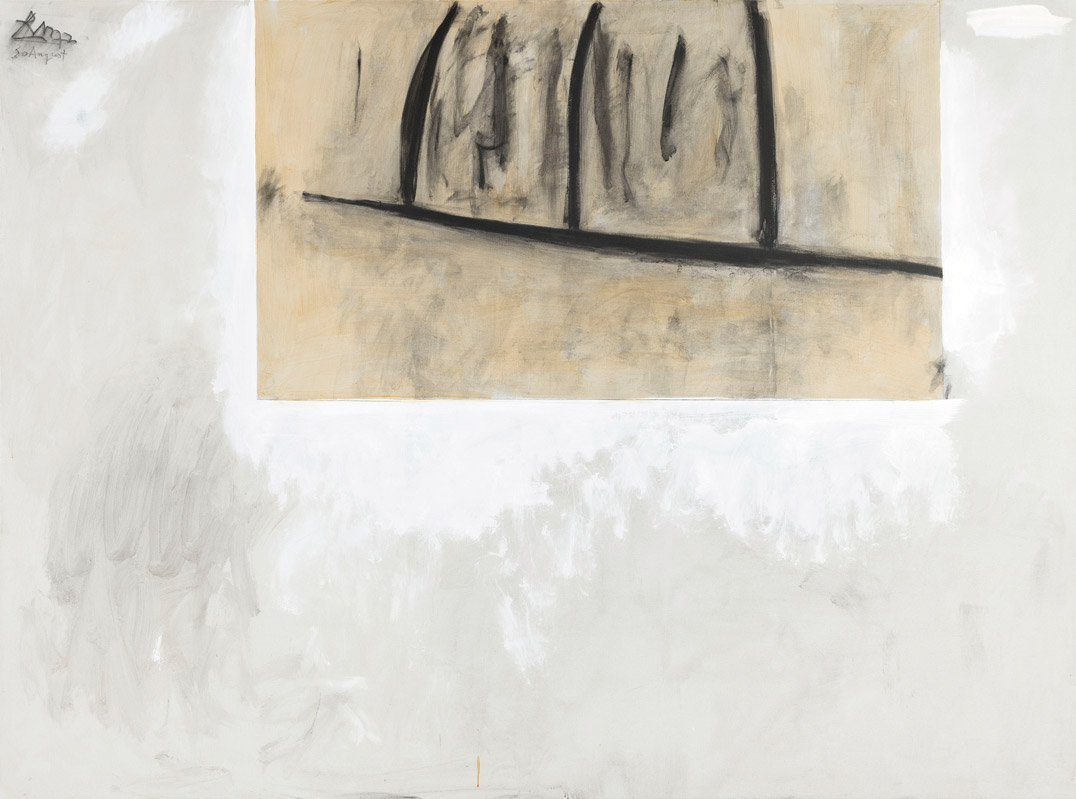

Helen Frankenthaler, Dawn Shapes, 1967

Acquired April 26, 1973

Clyfford Still, PH-338, 1949

Acquired November 10, 1973

Ad Reinhardt, Painting, 1950, 1950

Acquired January 8, 1974

Jackson Pollock, Untitled, 1951

Acquired March 29, 1974

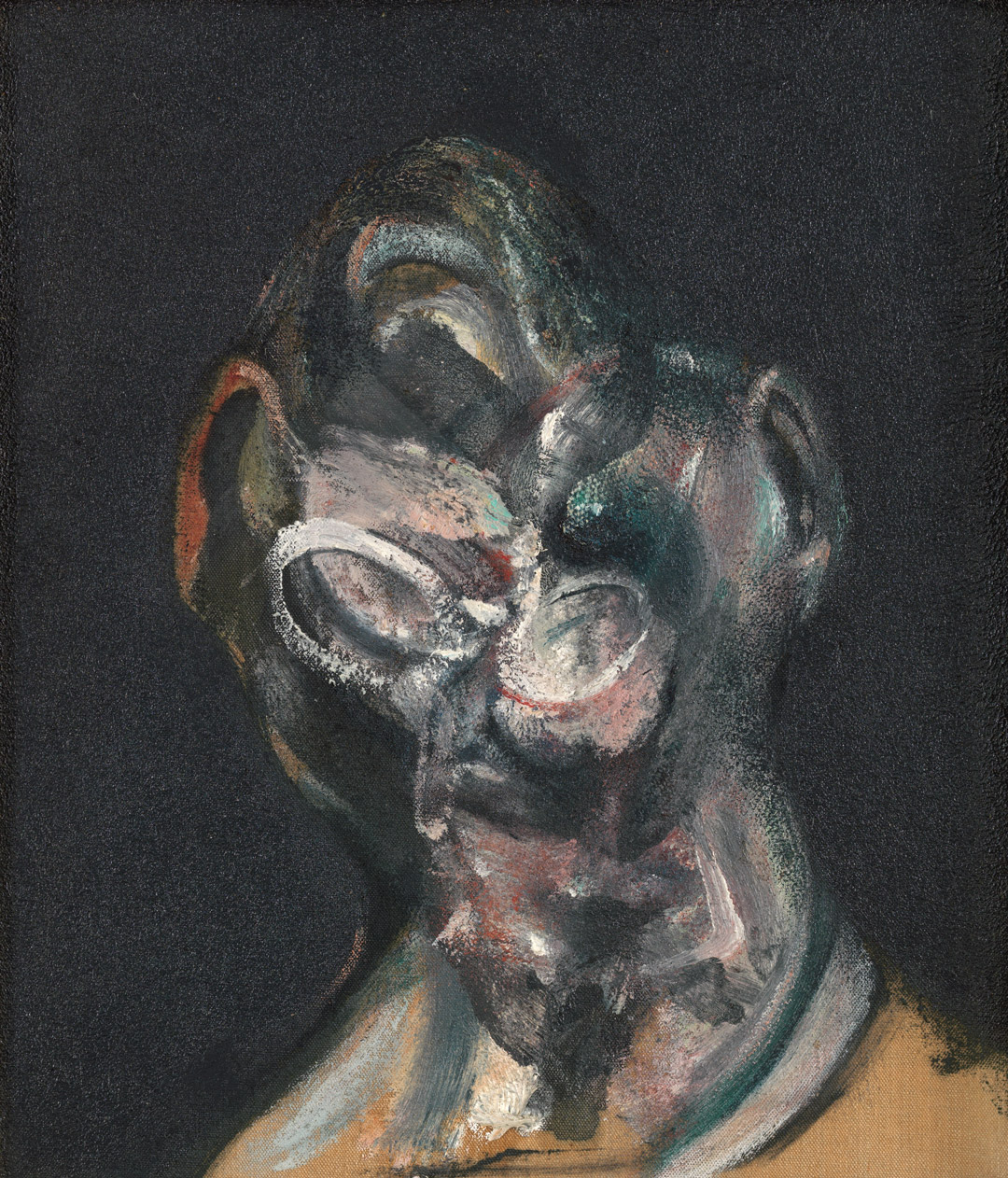

Francis Bacon, Portrait of Man with Glasses I, 1963

Acquired October 24, 1974

Alberto Giacometti, Femme de Venise II, 1956

Acquired January 2, 1975

Robert Motherwell, Irish Elegy, 1965

Acquired November 7, 1975

Francis Bacon, Study for a Portrait, 1967

Acquired November 20, 1976

Willem de Kooning, Town Square, 1948

Acquired December 6, 1976

Joan Mitchell, The Sink, 1956

Acquired September 12, 1977

David Smith, Cubi XXV, 1965

Acquired February 22, 1978

Philip Guston, To B.W.T., 1952

Acquired February 14, 1979

Mark Rothko, Untitled, ca.1945

Acquired November 12, 1980

Lee Krasner, Night Watch, 1960

Acquired November 19, 1981

Philip Guston, The Painter, 1976

Acquired February 1, 1982