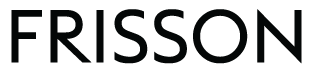

Crimson Spinning #2

1959

Adolph Gottlieb

American (1903–1974), oil on canvas, 90 × 72 in. (228.7 × 182.9 cm). Seattle Art Museum, Gift of the Friday Foundation in honor of Richard E. Lang and Jane Lang Davis, 2020.14.9. Photo by Spike Mafford / Zocalo Studios. © 2021 Adolph and Esther Gottlieb Foundation / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Crimson Spinning #2

Sanford Hirsch

“There are disparate feelings in both my painting and my concept of life: love-hate, freedom-restraint, openness-closedness. I recognize these and other feelings in my paintings after I have finished them. Opposites are my view of life.”

Adolph Gottlieb

Crimson Spinning #2, painted by Adolph Gottlieb in 1959, is considered one of the artist’s Burst paintings. These works are identified by two spherical forms, one defined and one expanding, positioned just above and below the horizontal center of Gottlieb’s vertical canvases. Burst paintings are quite simple in appearance; that is the artist’s plan. But their apparent simplicity is a device Gottlieb uses to convey complex emotional and formal subject matter. He was in his fifties when he began this phase of his art, and he was building on over thirty years of study, practice, and innovation.

Gottlieb’s career began in the early 1920s. As his work progressed, he became increasingly focused on the role of abstraction and meaning in visual art. His first major breakthrough occurred in 1941, when he began the group of paintings he labeled Pictographs. Pictographs were a unique concept that rejected the role of narrative or representation in painting. Rather than tell stories, Gottlieb wanted to connect with viewers on a subconscious level where meaning derived from an individual viewer’s emotional responses to a given work. To reach that goal, he created paintings that a viewer can take in in one glance. In his Pictographs, Gottlieb achieved these ends by structuring the image via a loosely drawn grid in order to eliminate illusionistic space and substitute simultaneity for narrative, and by the intuitive placement of spontaneous images within sections of the grid.

Toward the end of the 1940s, the all-over method of painting that was analogous to his use of the grid became a common device among several colleagues. From that time, Gottlieb began to explore how he could achieve his goals for abstract painting while moving away from the dense, crowded compositions of painters like Jackson Pollock or Willem de Kooning. Gottlieb labeled his paintings of the early to mid-1950s as Labyrinths, Imaginary Landscapes, or Unstill Lifes. In each of these types of painting, he utilized elements of the Pictographs to achieve the emotional and conceptual meaning he valued through consciously limited means. As he remarked to the curator Martin Friedman: “Since I eliminated almost everything from my painting except a few colors and perhaps two or three shapes, I feel a necessity for making the particular colors that I use, or the particular shapes, carry the burden of everything that I want to express.”1

Gottlieb’s Burst image developed organically from his Imaginary Landscape paintings (such as Red at Night, fig. 1, center). These earlier works consist of two horizontal registers placed on a horizontally oriented canvas with a few ovoid shapes suspended in the upper register. The lower register is usually densely packed with staccato brushstrokes and/or bits of imagery in near-chaotic action. In a 1956 painting titled Black, Blue, Red (fig. 1, right), Gottlieb oriented his canvas vertically, and the horizon line disappeared. The upper and lower registers were still in dynamic opposition, but imagery was concentrated in the interplay of two large, massed shapes. Gottlieb refined that image into his Burst paintings.

Burst paintings occupied Gottlieb almost exclusively from mid-1957 into 1960. Crimson Spinning #2 is part of that first intense exploration of the artist’s new direction. As was his usual practice, Gottlieb needed to work his ideas out on canvas, and he would explore each idea until he felt he had exhausted it. He explained to interviewer Gladys Kashdin in 1965:

What I’m looking for when I’m doing the painting—those things which I don’t know. In other words, I’m feeling my way and then I find something—and there to my surprise is something that wasn’t in the world before, and this can become more and more refined and subtle. . . . [I]f I start out with something which is absolutely new to me, I’ve never done anything like it before—this is a kind of a breakthrough. Then I develop it. I finally reach the point where it is no longer a breakthrough it is something that I already know. I’ve done this over many times. But then I begin to get nuances—then I’m interested in finding out how far I can go with this without exhausting it. What are the possibilities of exploring in this territory?2

The vertical orientation of the image is one of the important changes Gottlieb made in the Burst paintings. The majority of them are between 7 and 9 feet high and about 5 and 7 1/2 feet wide, placing them in direct relation to the proportions of an individual viewer. The critic and curator Lawrence Alloway observed that Gottlieb’s Bursts are “a subtle and sustained contribution to the investigation of the visual-physical relationships of image and spectator that is central to the Abstract Expressionists’ big pictures.”3 The historian Pepe Karmel likewise noted the importance of the physical aspect of these relationships, stating, “Gottlieb used the language of painting to evoke these qualities of the physical environment, determining the conditions of our existence as human beings.”4

Alloway also spoke of what he called the “dyadic” nature of these works.5 Gottlieb’s paintings are complete statements within which the two main forms relate to each other and, as a pair, to the entire painting—including the exact physical dimensions of the canvas. The broader surface areas of his paintings, which are usually referred to as fields, are as carefully painted as the paired forms that occupy them, and with which they contrast. Gottlieb created images in which each element is part of a subtle and tenuous balance. That aspect of Gottlieb’s work is another part of meaning, since balance is a momentary state that is bound to change. The image thus parallels the experience of emotional states: both are transitory, precariously balanced, the result of and subject to opposing urges and tendencies; both develop over time and include a history of that development. In contrast to the “action painting” of the period, usually defined as a record of the unstructured flow of the artist’s hand and body in creating a painting, Gottlieb paints the act of being in a moment.

In Crimson Spinning #2, the two large forms interact with each other in various ways. The upper form has more regular contours and is encircled by a halo of color that might imply either stasis or movement, while the lower form is unencumbered and expands toward the outer edges of the canvas. To exaggerate both the difference and the connection between these forms, the upper field is painted a warmer shade, while the lower field is overpainted in a cold white and has no clearly defined edge. Instead, the lower field alternately blends with and encroaches onto the upper, forming an irregular curve that extends across the width of the canvas. Gottlieb’s theme here is the constancy of change.

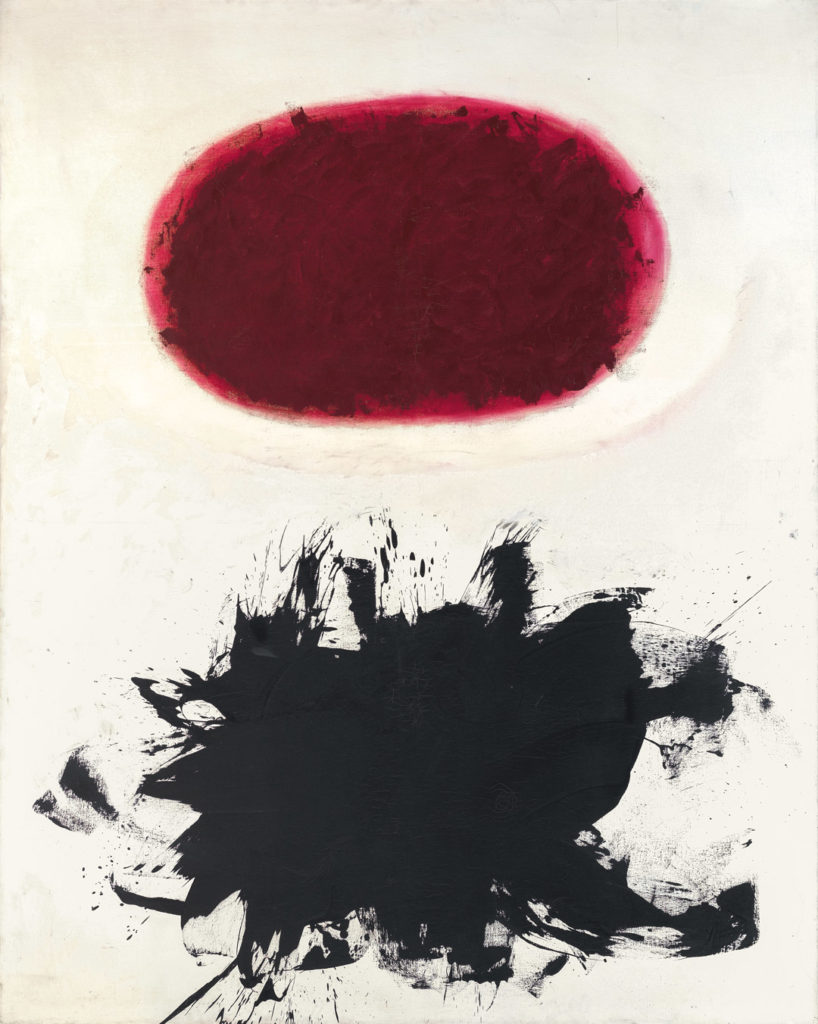

To realize this abstract thought as a painting, the artist created each form with different paints, using different tools. The final layer of the upper form is painted with thick artist’s oil paint applied with a brush and palette knife, while the lower form consists of a commercial paint applied using a squeegee with enough speed and force to produce the drips and splashes that vector out from its edges (fig. 2). The juxtaposition of the contained and open spheres marks one statement of a whole carefully built of opposing pairs. Despite the ultimate appearance of balance, by locating those forms off-center (actually, off-two-centers), Gottlieb underscored the transitory nature of that balance. Either form has the capacity to subsume, exchange with, or replace the other. What we are shown in the painting is a moment in which all elements are in balance, but it is an active moment that is open to infinite variation.

In articulating the large forms in the painting, Gottlieb emphasized the interrelatedness of these different, but mutually supportive, bodies. The shapes convey similarity, despite the two forms’ opposite contours. The flat surface of the lower form directs the eye to scan toward the expanding contours, while the dense and varied surface of the upper form draws vision inward, reinforced by the brushworkand knife work and the more regular curve of the red underpainting. The relationships between the field and the large forms draw on similar contrasts of methods and materials. The apparent simplicity of the image at first glance belies its complex construction.

The title Crimson Spinning #2 makes clear that this is the second painting of the same name. Crimson Spinning (fig. 3), also painted in 1959, while compositionally similar, is substantively different. Gottlieb titled his paintings after they were completed, based on his own reactions to each canvas. Most of the titles of his later works are somewhat neutral, like Crimson Spinning,6 as the artist did not want to impose or imply a specific meaning for any work. He insisted that a painting has broader meanings than even the artist might be aware of, and he did not want to limit any viewer’s ability to relate to his paintings. Nonetheless, that humanist impulse also drove his determination to title his paintings—as opposed to the practice of several colleagues who used numbers instead of titles. Gottlieb reacted strongly when asked why he gave his paintings descriptive titles, rather than numbering them. His answer: “Prisoners have numbers.”7

The philosopher Finley Eversole wrote a lengthy essay about another Burst painting, titled Blast I (1958, Museum of Modern Art, New York). Among his observations are the following thoughts that apply to all of Gottlieb’s Burst paintings: “Much of the poetic power of Blast I comes from its simplicity as an abstract image, purified of all specific historical and cultural content. Its truth is existential, not cultural. . . . Behind it stands the archetypal war of opposites—Freud’s eros and thanatos—and a thousand myths of battle between sun-god-heroes and the dragons of the deep.”8 This fundamental opposition—the dependence of one pole on its opposite—was key to the artist, who called himself a “conceptual painter.”9 It can, and does, contain all aspects of perception, bringing us closer to what Gottlieb termed his “view of life” in the epigraph to this essay. The word “perception” in the English language has several definitions. According to Merriam-Webster’s dictionary, these include: “a result of perceiving (observation), a mental image (concept), awareness of the elements of environment through physical sensation (color perception), and a capacity for comprehension.”10 Gottlieb believed that his role as an artist was to create images that embody all of these possible interpretations, simultaneously. In making his paintings, he used his knowledge and skills as a painter to encompass the complexity that Eversole described, and more. Gottlieb both agreed with Eversole’s interpretation and believed that it was only one aspect of the kinds of experiences his manipulation of these images could express. “I don’t identify my paintings when I work with any philosophy of any sort. And I don’t think that my painting is the direct expression of a certain philosophy—there are too many other elements in it which have to do with a sensuous reaction and with a physical effect on the eyes and traditions of painting and so on.”11

The complexity of Gottlieb’s art is often overlooked. Through carefully constructed pairs of opposites, both visual and actual, he was committed to presenting the abstraction and imperfections that he observed as constants: “We have aspirations and we have defeats, and in the life process we have all the experiences which make us feel anxiety or terror or joy and so on. I think all of this is legitimate material, which enters into a painting, but these are abstractions.”12 Another important pairing, when considering Gottlieb’s work, is of the particular painting with the individual viewer. His is an art that communicates one to one rather than attempting to reach a mass audience. It avoids concepts like the “sublime,” which was the goal of some of his friends, like Barnett Newman and Mark Rothko. Gottlieb doesn’t believe in absolutes; he accepts limitations and doubt as experience. In his view, art and language are themselves abstractions that, in their distinctive ways, reflect and allow individuals to consider and review the imperfect realities they must manage. Crimson Spinning #2, like Gottlieb’s other late paintings, defines limits and potential in the same moment.

Author

Sanford Hirsch is executive director of the Adolph and Esther Gottlieb Foundation. He has organized many exhibitions of the work of Adolph Gottlieb, including the 1981 retrospective at the Corcoran Gallery of Art, for which he also contributed to the accompanying catalogue (Arts Publisher and the Adolph and Esther Gottlieb Foundation, 1981).

Notes

Epigraph Adolph Gottlieb, quoted in Stephen Polcari, “Gottlieb on Gottlieb,” Nightsounds, March 1969, 11.

1 Adolph Gottlieb, interviewed by Martin Friedman, August 1962, tape 2A, transcript, p. 6, Adolph and Esther Gottlieb Foundation, New York.

2 Gladys Kashdin, “Conversation with Adolph Gottlieb,” New York, April 28, 1965, typescript of tape recording, p. 13, Adolph and Esther Gottlieb Foundation, New York.

3 Lawrence Alloway, “Adolph Gottlieb and Abstract Painting,” in Adolph Gottlieb: A Retrospective (New York: Art Publisher, 1981), 57.

4 Pepe Karmel, “Artist and Cosmos,” in Adolph Gottlieb: Gravity, Suspension, Motion: Paintings, 1954–1972 (New York: Pace Gallery, 2012).

5 Alloway, “Adolph Gottlieb and Abstract Painting,” 57.

6 For example, he titled some other paintings from 1959 Aureole, Black and Black, Levitation, and Cadmium Red above Black.

7 Friedman interview, 51.

8 Finley Eversole, “Blast I: Image of Renewal,” Art Directions, no. 4 (Summer 1967): 7.

9 Friedman interview, 40.

10 Merriam Webster, s.v. “Perception,” accessed December 22, 2020, http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/perception.

11 Kashdin, “Conversation with Adolph Gottlieb,” 15.

12 “A Discussion between Sister Corita, I.H.M. and Adolph Gottlieb,” December 1964, unedited typescript, p. 7, Adolph and Esther Gottlieb Foundation, New York.

Explore the Collection

Sort by Chronology

Sort by Artist

Sort by Author

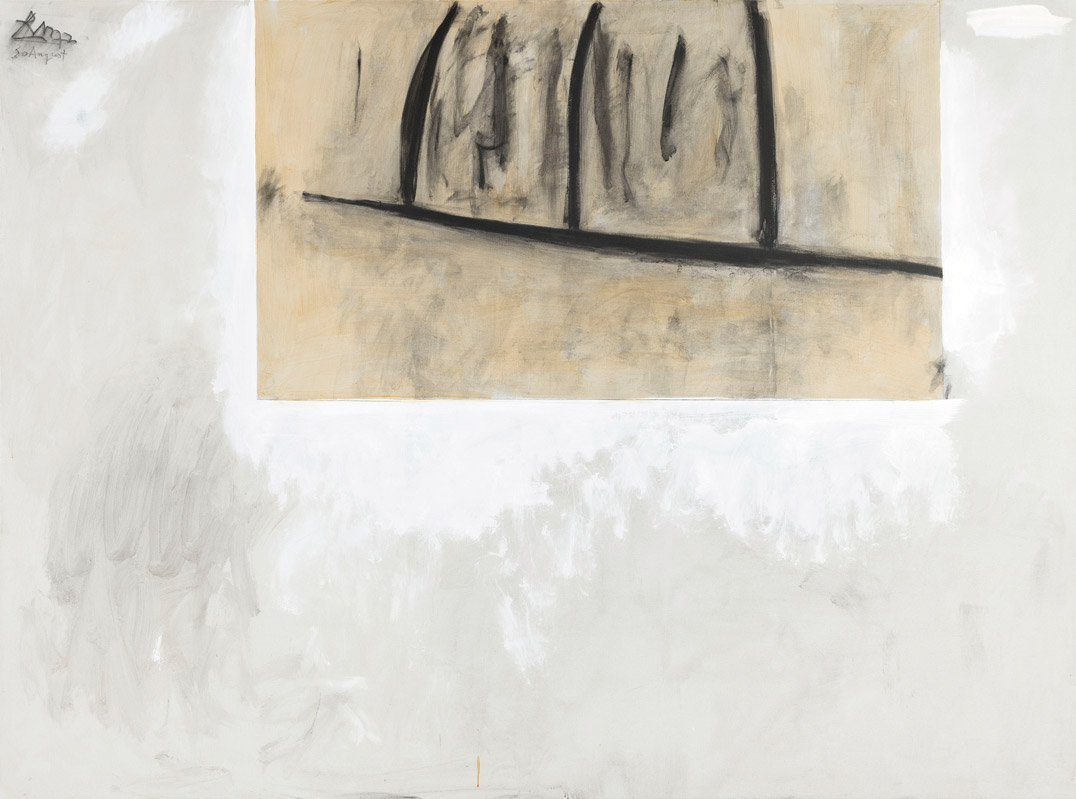

Franz Kline, Painting No. 11, 1951

Acquired November 13, 1970

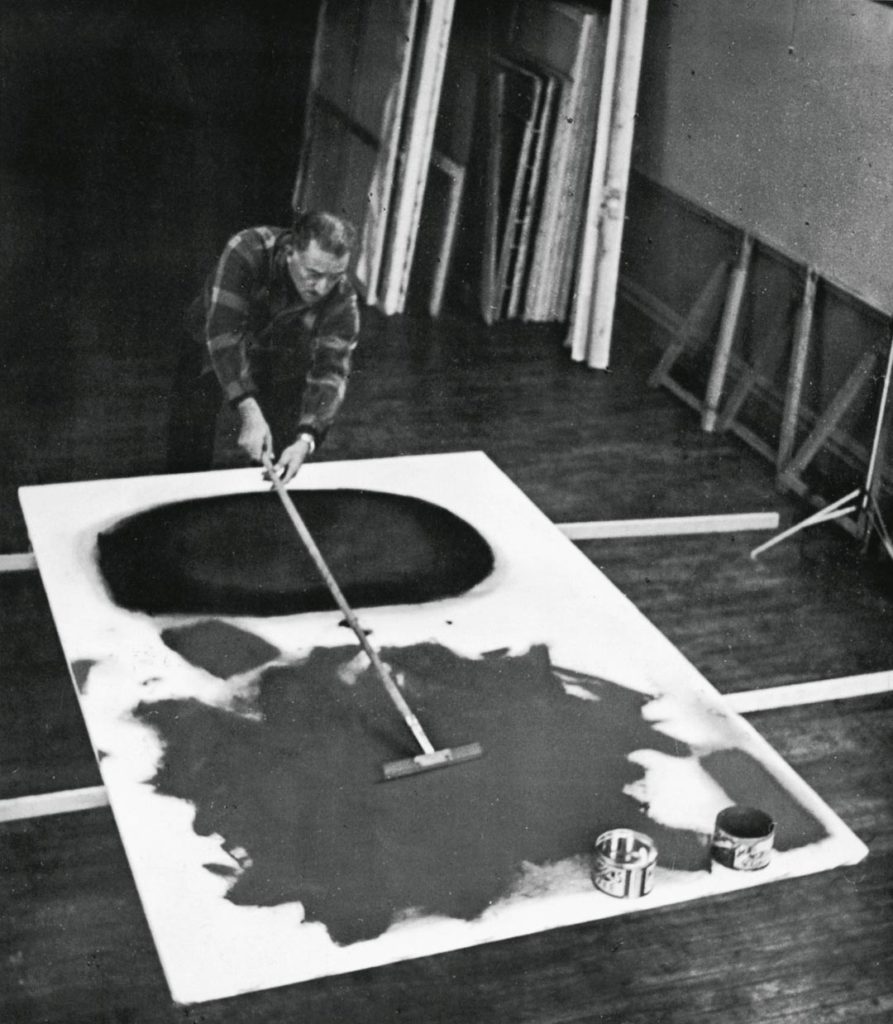

Mark Rothko, Untitled, 1963

Acquired May 18, 1972

Robert Motherwell, Before the Day, 1972

Acquired October 12, 1972

Adolph Gottlieb, Crimson Spinning #2, 1959

Acquired December 11, 1972

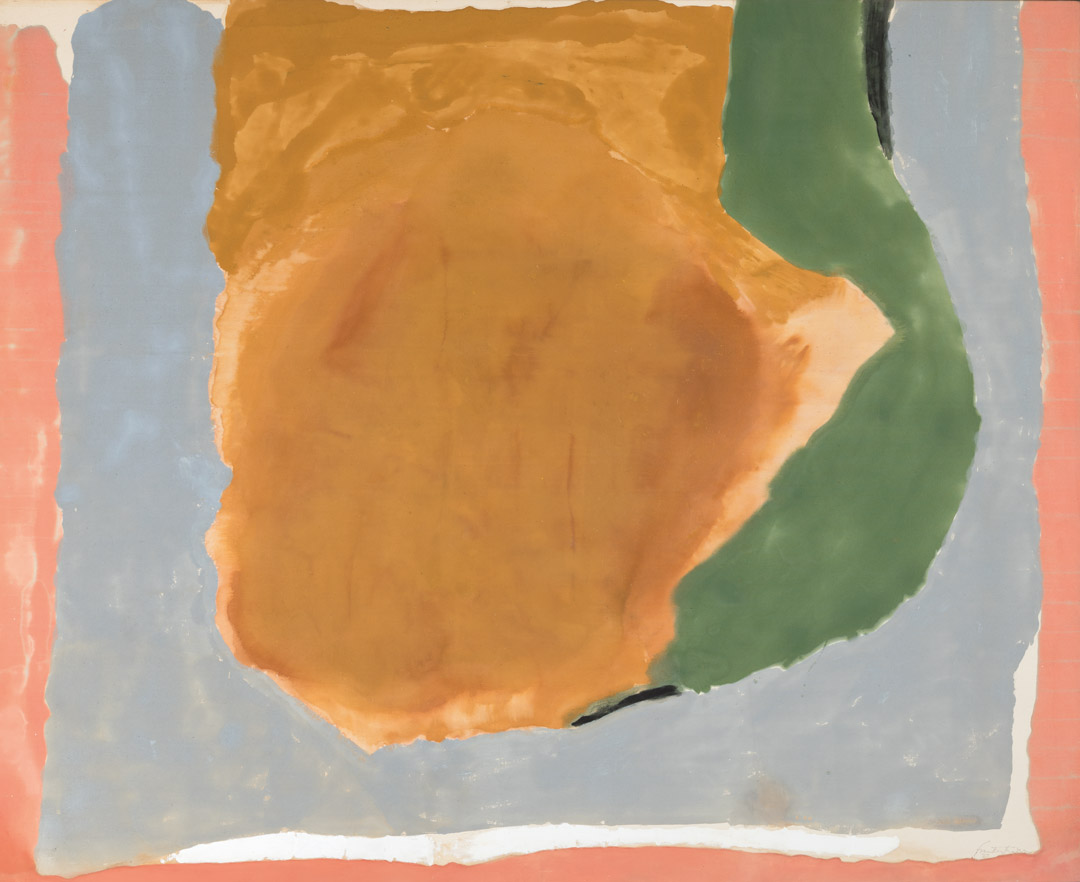

Helen Frankenthaler, Dawn Shapes, 1967

Acquired April 26, 1973

Clyfford Still, PH-338, 1949

Acquired November 10, 1973

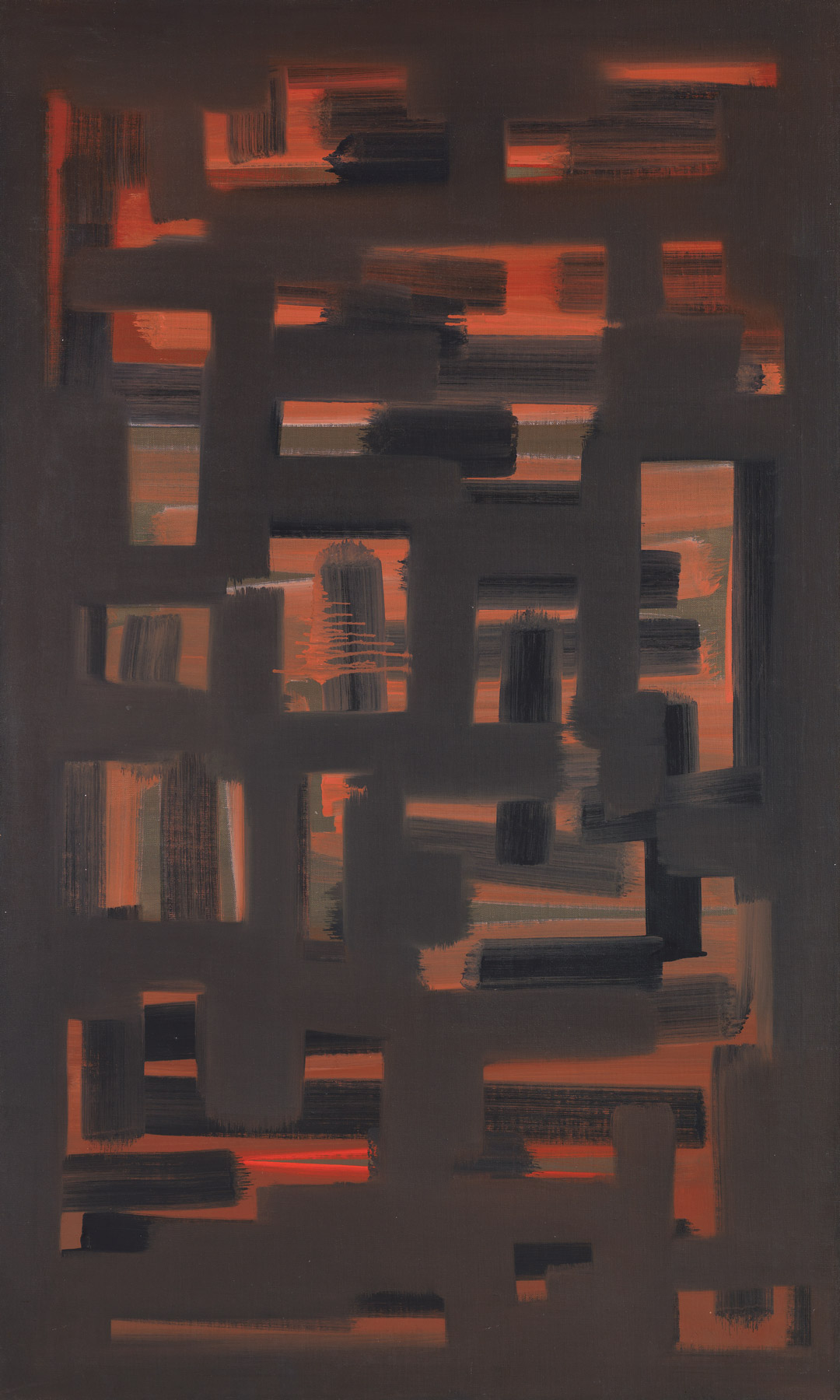

Ad Reinhardt, Painting, 1950, 1950

Acquired January 8, 1974

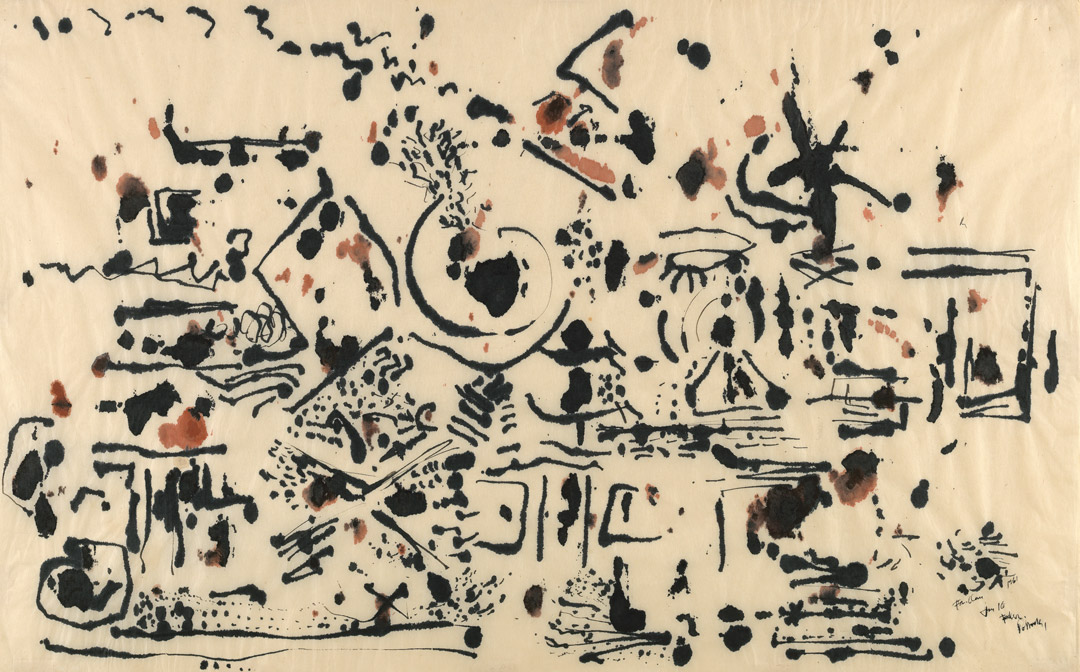

Jackson Pollock, Untitled, 1951

Acquired March 29, 1974

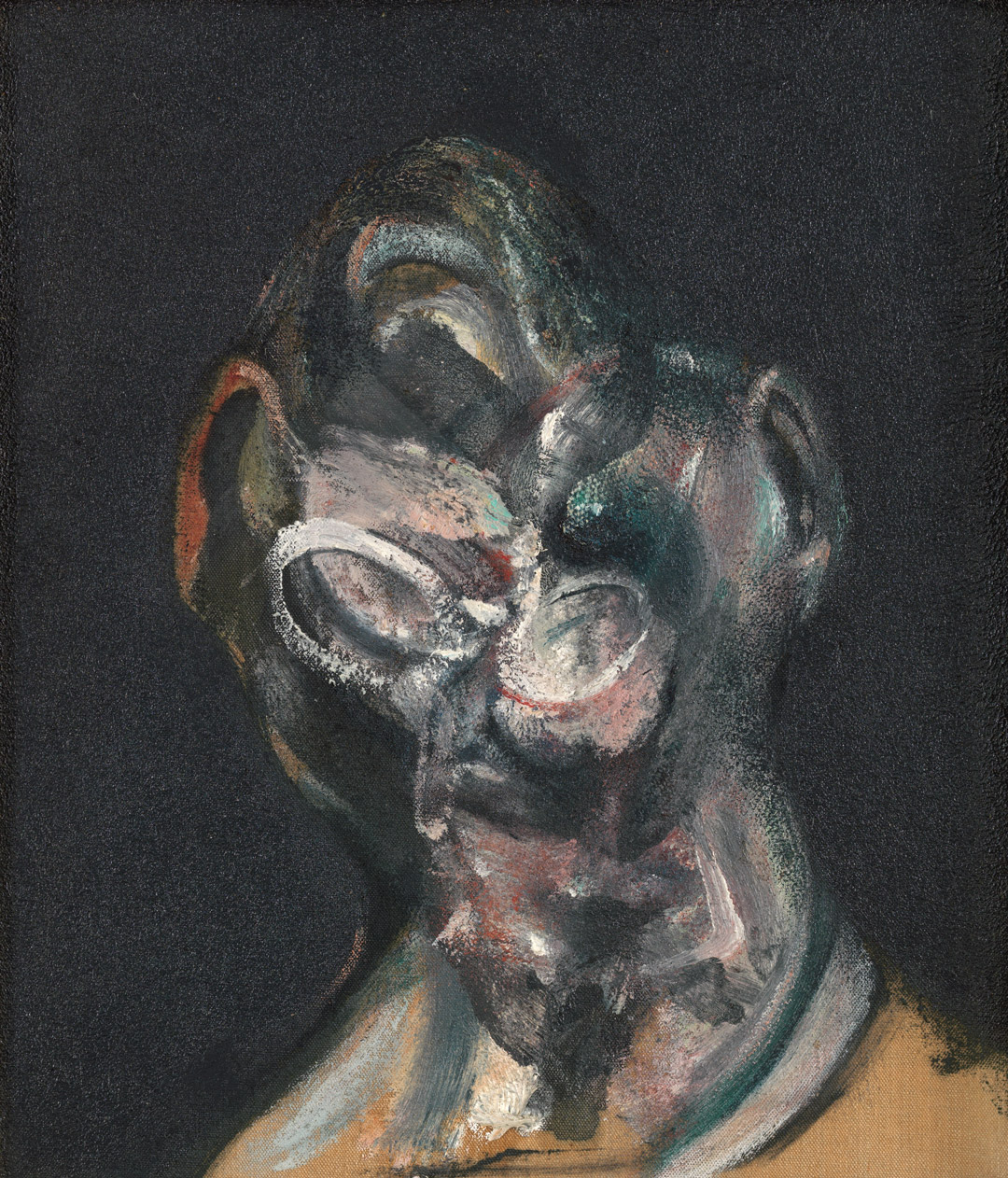

Francis Bacon, Portrait of Man with Glasses I, 1963

Acquired October 24, 1974

Alberto Giacometti, Femme de Venise II, 1956

Acquired January 2, 1975

Robert Motherwell, Irish Elegy, 1965

Acquired November 7, 1975

Francis Bacon, Study for a Portrait, 1967

Acquired November 20, 1976

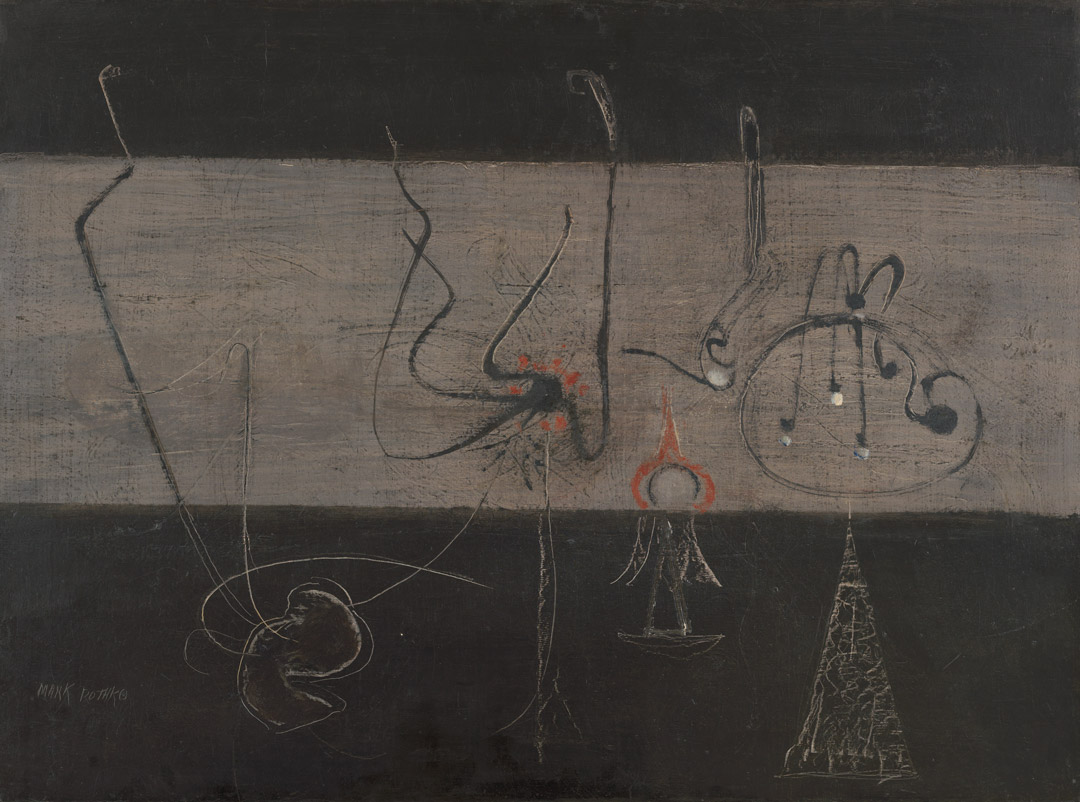

Willem de Kooning, Town Square, 1948

Acquired December 6, 1976

Joan Mitchell, The Sink, 1956

Acquired September 12, 1977

David Smith, Cubi XXV, 1965

Acquired February 22, 1978

Philip Guston, To B.W.T., 1952

Acquired February 14, 1979

Mark Rothko, Untitled, ca.1945

Acquired November 12, 1980

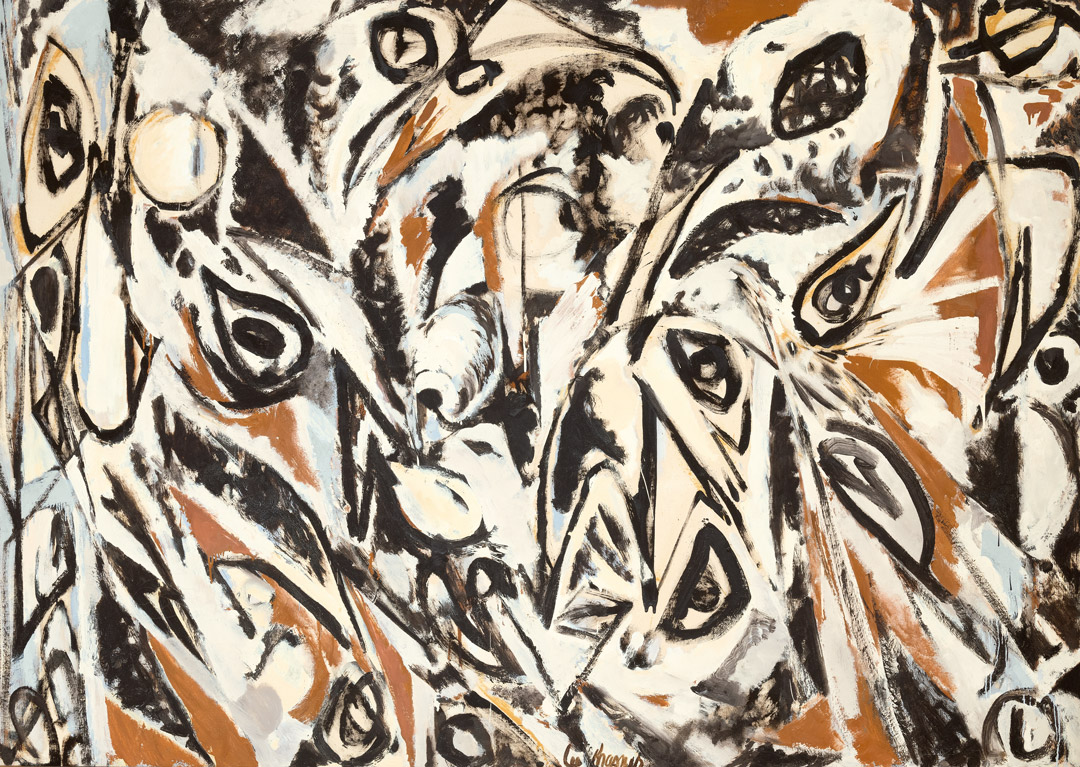

Lee Krasner, Night Watch, 1960

Acquired November 19, 1981

Philip Guston, The Painter, 1976

Acquired February 1, 1982