Femme de Venise II

1956

Alberto Giacometti

Swiss (1901–1966), bronze, overall: 473/8 × 53/4 × 127/8 in. (120.2 × 14.8 × 32.7 cm). Seattle Art Museum, Gift of the Friday Foundation in honor of Richard E. Lang and Jane Lang Davis, 2020.14.8. Photo by Spike Mafford / Zocalo Studios. Courtesy of Friday Foundation. © 2021 Alberto Giacometti Estate / VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris.

Femme de Venise II

Catherine Grenier

The Swiss-born sculptor Alberto Giacometti was just 21 years old in January 1922 when he arrived in Paris to study under Antoine Bourdelle at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière. Subsequently, though he regularly returned to Switzerland to visit his family, it was in France, in Paris, that he made his career. Throughout the 1920s, Giacometti explored and experimented with numerous styles, from archaism and primitivism to post-Cubism, without ever fully abandoning figuration. In 1929, his planar sculptures, which verged on abstraction, began to attract attention, notably from the Surrealist circle around André Breton, which Giacometti joined in 1930. But this foray into Surrealism was brief, and beginning in 1935 Giacometti distanced himself from the movement and returned to modeling his works from life. Representing the human figure as he saw it became his main concern. Between 1935 and 1947, Giacometti struggled with self-doubt, destroyed much of his work, and rarely exhibited. During this period, his sculptures progressively diminished in scale until some stood just a few centimeters tall; only after World War II did his works grow taller again. This elongation, along with the lumpy surfaces of his sculptures, became one of the principal characteristics of the artist’s mature style, as exemplified in the Lang Collection’s Femme de Venise II. Works in this new style contributed to Giacometti’s steadily growing fame throughout the 1950s.

In December 1955, Giacometti was invited to represent France at the next Venice Biennale—as a sculptor. The request came at a difficult moment: frustrated by his sculptural practice, he was instead more focused on painting. Nevertheless, gratified by the honor of the invitation, he accepted and quickly set to work, as the biennale would open the following year.

The artist was accustomed to periods of discouragement and doubt in his creative work—grappling with challenges in both his sculpture and his painting. That feeling of incapacity had weighed heavily on him throughout World War II, most of which he spent in Switzerland, but he had experienced a respite after the war. His return to Paris after several years in Geneva, his reunion with his studio and friends, and also the fresh perspective of an exhibition at the Pierre Matisse Gallery in New York had all fostered renewed productivity and the creation of numerous works in a new style. Yet, following a reassuring few years in which each work seemed to advance from the preceding ones, and despite the success he was enjoying, in 1952 the artist was again undermined by uncertainty. He began endlessly reworking his pieces. “Actually,” he explained to Pierre Matisse, “it’s not so much about exhibiting anymore for me, but rather seeing if I can still make a sculpture and painting stand. I’m terribly stuck; I’ve done everything to get to this point but now I need to get out; I’ve called into question every grain of plaster, I’ve hit bottom, that’s at least one thing that I’ve accomplished!!!” he lamented.1 The year 1953 brought a period of transition in which Giacometti vacillated between highs and lows. That spring, he turned back to sculpture and focused on realizing female nudes and busts. His brother Diego, who served as Giacometti’s studio assistant and collaborator, casting his plaster models in bronze, was at his side. “Alberto, I hope you’re continuing with your sculpture; whatever you do, don’t demolish them,”2 he wrote, worried that Giacometti would destroy his work while making it, as he had too often done in the past.

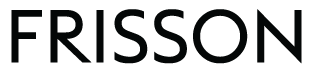

His small studio, where he labored fiercely, was filled at the time with sculptures in progress, along with some abandoned works. The philosopher Isaku Yanaihara, whom Giacometti met in November 1955 and who would become his model, described this “prodigious accumulation.” When he first visited the artist, on November 17, he was astounded by the condition and mess of the “very poorly lit studio with its windows too small. . . . Near the entrance, there was a large table against the wall with an entire collection of dusty bottles and old brushes thrown into a pile.” Yet, Yanaihara continued, amid the chaos he discovered “what one can only describe as the final residue of human existence once stripped of anything superfluous; like phantoms and yet incredibly fraternal, audacious and with unending humility, a row of plaster figurines that seemed to be frozen in place.”3 Characterized by their spindly appearance, the nude female figures Yanaihara saw evoke Egyptian funerary sculpture, especially in the massive bases anchoring each one (fig. 1). Their extreme proportions, stretched almost to abstraction, enact a kind of violence that can also be felt in the rendering of the surface, vividly cut with the sculpting knife. “It’s in sculpture that I feel something like a contained violence that touches me,” the artist explained.4 Moreover, his interest in archaeological objects from ancient Egypt and Greece, deformed and reshaped over time, drove him to retain in his own sculptures the accidental traces left by the modeling and plaster casting processes.

It was a month after meeting Yanaihara when Giacometti agreed to represent France at the Venice Biennale as a sculptor, with Jacques Villon representing French painting. A few weeks later, Giacometti had to refuse a request to represent his native Switzerland at the same biennial. These twin honors followed a series of recent international achievements, including a one-man show at the Santa Barbara Museum of Art in 1953, his first at an American museum, and two important retrospectives that opened in 1955 at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York and then at the Arts Council Collection in London. During that same period, a third exhibition had traveled to three German museums. Despite the fact that Giacometti had been working in Paris for thirty years, recognition came first from abroad—in particular from the United States, where his most important collectors were. The French invitation in late 1955 was therefore all the more welcome. In lieu of representing Switzerland at the biennale, Giacometti was asked to present a retrospective at the Museum of Fine Arts in Bern, which would fully establish his reputation as a leading European artist of his generation.

Giacometti prepared for the two exhibitions simultaneously and began a series of female figures. These departed from the recent nudes realized in sessions with his wife, Annette, as model, in which he had turned away from the hieratic, or highly stylized, stances reminiscent of Egyptian priestly gestures that he had sculpted from memory after the war. Those earlier, elongated figures were especially distinctive for the diminutive scale of the heads in sharp contrast with the proportions of the bodies. He now embarked on a series of medium-size, attenuated female figures, each unique despite their similarities to one another. The choice of scale reflected his desire to eschew heroic qualities in his sculpture and to play with the viewer’s sense of simultaneous proximity and distance—a sense reinforced by the disproportion between the figures and their tall, Egyptian-style pedestals. Even if the artist was spurred by the pressure of looming exhibition deadlines, the resulting series is in no way simplistic. Yanaihara, who sat as a model for Giacometti a few months later, vividly attested to his turbulent creative process. When confronting the material, the artist swore, destroyed, and began again, every day drawn back to the studio by the failure of the stint before: “He clenched his teeth while forcing himself to paint and from his mouth surged the darkest phrases, cries of despair and curses.”5 According to Yanaihara, Giacometti was stimulated by the failure he strove to combat. Yet the expressions of despair—“Catastrophe!” “That’s no good!” “Shit!”—alternated with signs of renewal—“There’s a start!”6

Nearly a decade earlier, in 1947, Giacometti had been seized by a kind of frenzy that pushed him to create nearly identical sculptures one after another. “Recently, I’ve been making a life-size human figure every night,”7 he wrote his mother at the time. Each had the same attitude: immobile and straight, the arms extended along the body. Those shadowlike, slender figures were stripped down to the essential, their irregular surfaces capturing the light in bursts. He drew on that model in executing the works for the biennale, which he would title Femmes de Venise. Despite difficulties and discouraged outbursts, he completed the 1956 series in time. “I made thirteen medium figures rendered a bit like the ones from 47 that I sent you,” he explained to Pierre Matisse. “That was very useful: I think there was a progression from one to the other, right up to the last one, which Diego is casting now.”8

Ten were presented at the biennale, in plaster cast versions with the surface painted or incised (fig. 2). Hieratic, with arms hanging alongside the body, these female figures were a kind of synthesis between the 1947 series made from memory and inspired by antiquity, and the nudes that Giacometti made from life when Annette began posing for him.9 Thus, they brought together the timelessness and generalization of Egyptian figures and Greek korai (figs. 3 and 4) with the sense of embodiment that belongs to portraiture. Like the earlier group, the biennale figures seem very similar when seen from afar, but differences emerge upon closer examination. Of the thirteen models initially created, only ten would survive, nine of which would later be cast in bronze.

The writer Jean Genet, who at the time that the Femmes de Venise were being executed came to sit as a model for the artist, described them in this way:

Aside from his walking men, all of Giacometti’s statues have feet that seem bound to a single, angled block, very thick, more like a pedestal. The body stems from there and supports—far away, very high—a miniscule head. That enormous mass of plaster or bronze—proportionally to the head—might lead one to believe that its feet are loaded with all the materiality the head has gotten rid of. . . . Not at all; between these massive feet and head, an uninterrupted exchange occurs. These ladies are not dragging through heavy mud: at dusk, they will glide down a slope drenched in shadows.10

Among this series of female nudes, which the artist showed individually immediately after the biennale, Femme de Venise II goes the farthest in sculptural simplification. The utter rejection of anecdotal detail, the arms conjoined along the length of the body, and the simple suggestion of hair confer a radical essence. Feigning nothing, this reduction of the means of representation, as Genet articulates so well, authentically conveys the feeling of a glorious humanity. In that paradox, one finds the very quality that so struck young Giacometti upon discovering Egyptian sculpture: “These past few days, I’ve gone several times to the museum of Egyptian art. Now that is real sculpture. They kept only what was necessary for the entire figure, there isn’t even a hole for a hand to fit in, and yet one has the impression of movement and form that is extraordinary in its manner,” he wrote his parents in 1920.11 Genet, whose book L’Atelier d’Alberto Giacometti is one of the finest literary texts on an artist’s studio, poetically describes this turning back in time toward the essence of humanity by the sculptor: “Every work of art, if it wants to achieve the grandest proportions, must, with patience, with infinite diligence from the time of its development, descend into millennia past, reunite if it may with the immemorial night inhabited by the dead who will see themselves in the piece.”12 In his dialogue with the past, Giacometti creates figures that are profoundly material, as evidenced in his highly worked and rough surfaces. At the same time, the artist arrived at silhouettes that are so starkly reduced that they border on abstractions.

Author

Catherine Grenier is director of the Fondation Giacometti and former deputy director of the Musée National d’Art Moderne – Centre Pompidou, Paris. She has published extensively on the work of Alberto Giacometti, including the recent books Alberto Giacometti, L’homme qui marche (Fondation Giacometti-institut and Fage éditions, 2020) and Alberto Giacometti, a Biography (Flammarion, 2018).

Notes

Translated from French by Molly Yakusan Stevens.

1 Alberto Giacometti to Pierre Matisse, late April 1952, Pierre Matisse Gallery Archives, Morgan Library, New York.

2 Diego Giacometti to Alberto and Annette Giacometti, April 11, 1953, Giacometti Foundation Archives, Paris.

3 Isaku Yanaihara, Dialogues avec Giacometti (Paris: Allia, 2015), 25.

4 Alberto Giacometti, “Entretien avec Georges Charbonnier,” radio interview, Radio France, 1954.

5 Yanaihara continued, “And sometimes even, on top of it all, he hurled an aaah! as loudly as possible. The little Rue Hippolyte-Maindron where his studio was located was most often deserted, but anyone who by chance passed by on a night in November 1956 would have certainly been frightened by the strange vociferations coming through the walls of that shaky shack. It sounded like the delirium of a senseless madman.” Yanaihara, Dialogues avec Giacometti, 141.

6 Yanaihara, Dialogues avec Giacometti, 141.

7 Alberto Giacometti to Annetta Giacometti, fall 1957, Alberto Giacometti-Stiftung, Zurich.

8 Alberto Giacometti to Pierre Matisse, June 1956, Pierre Matisse Gallery Archives, Morgan Library, New York.

9 Giacometti worked with certain models for long periods of time. His wife, Annette, and brother Diego were frequent models.

10 Jean Genet, L’Atelier d’Alberto Giacometti (Paris: L’Arbalète, 1963), n.p.

11 Alberto Giacometti to Giovanni and Annetta Giacometti, December 8, 1920, Alberto Giacometti-Stiftung, Zurich.

12 Genet, L’Atelier d’Alberto Giacometti, n.p.

Explore the Collection

Sort by Chronology

Sort by Artist

Sort by Author

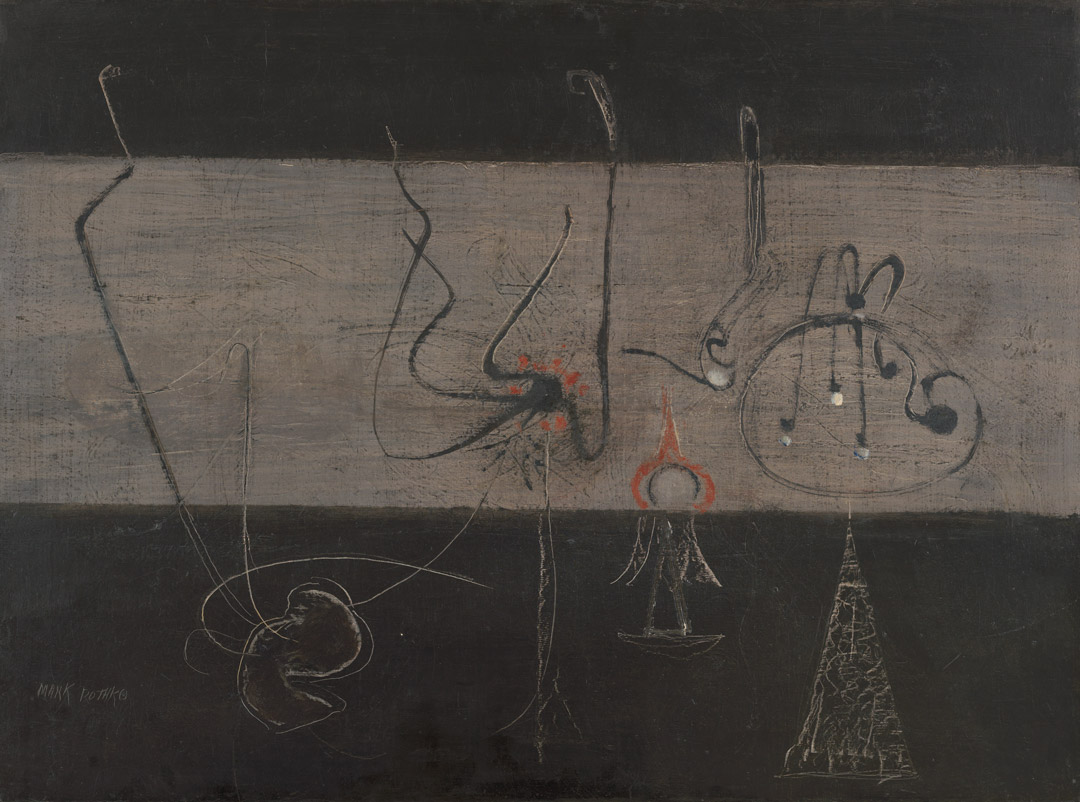

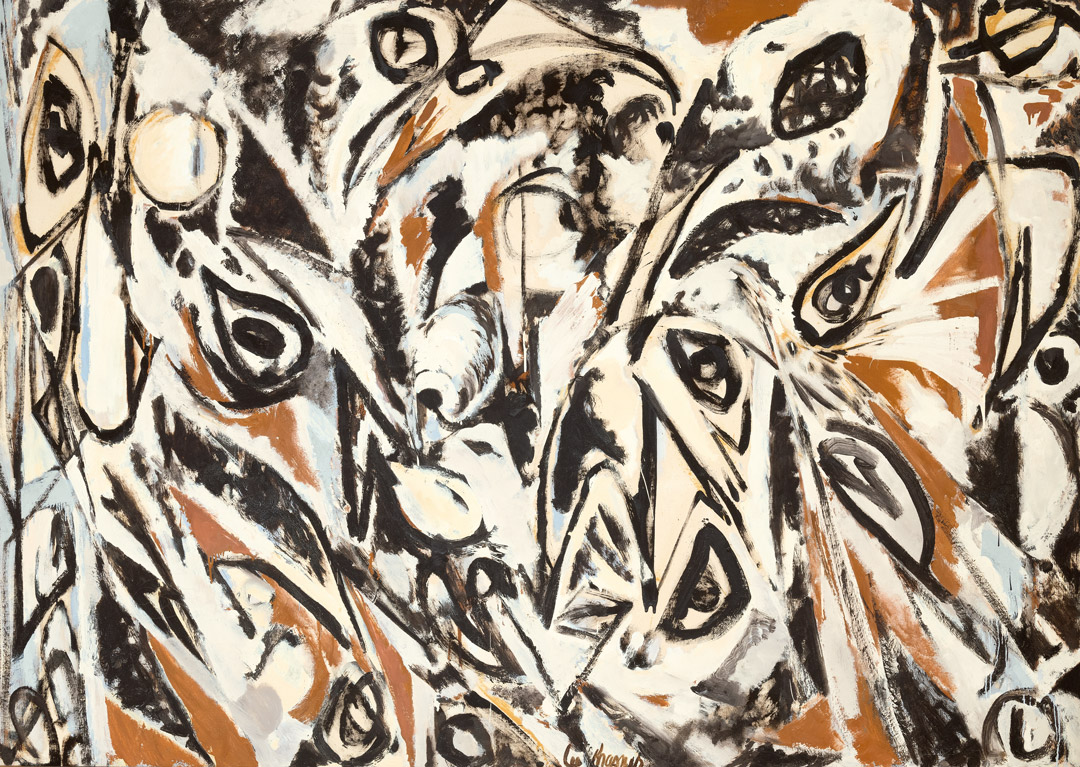

Franz Kline, Painting No. 11, 1951

Acquired November 13, 1970

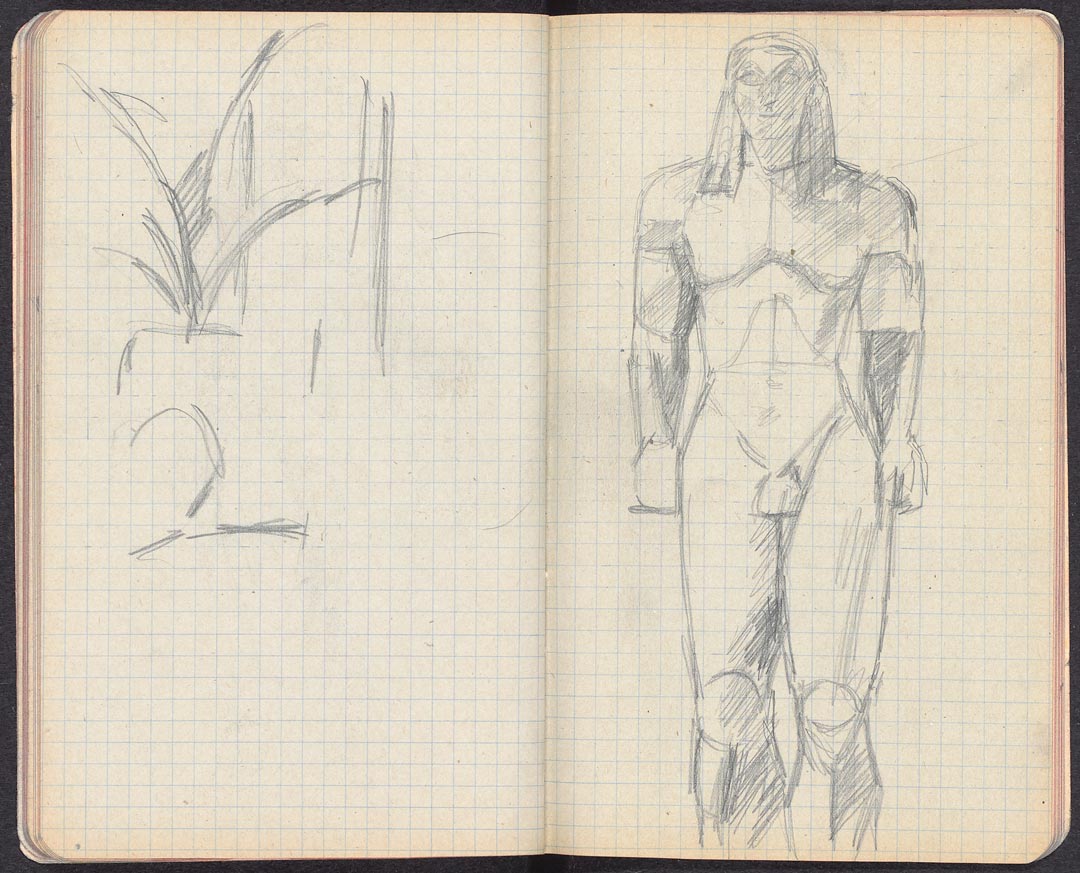

Mark Rothko, Untitled, 1963

Acquired May 18, 1972

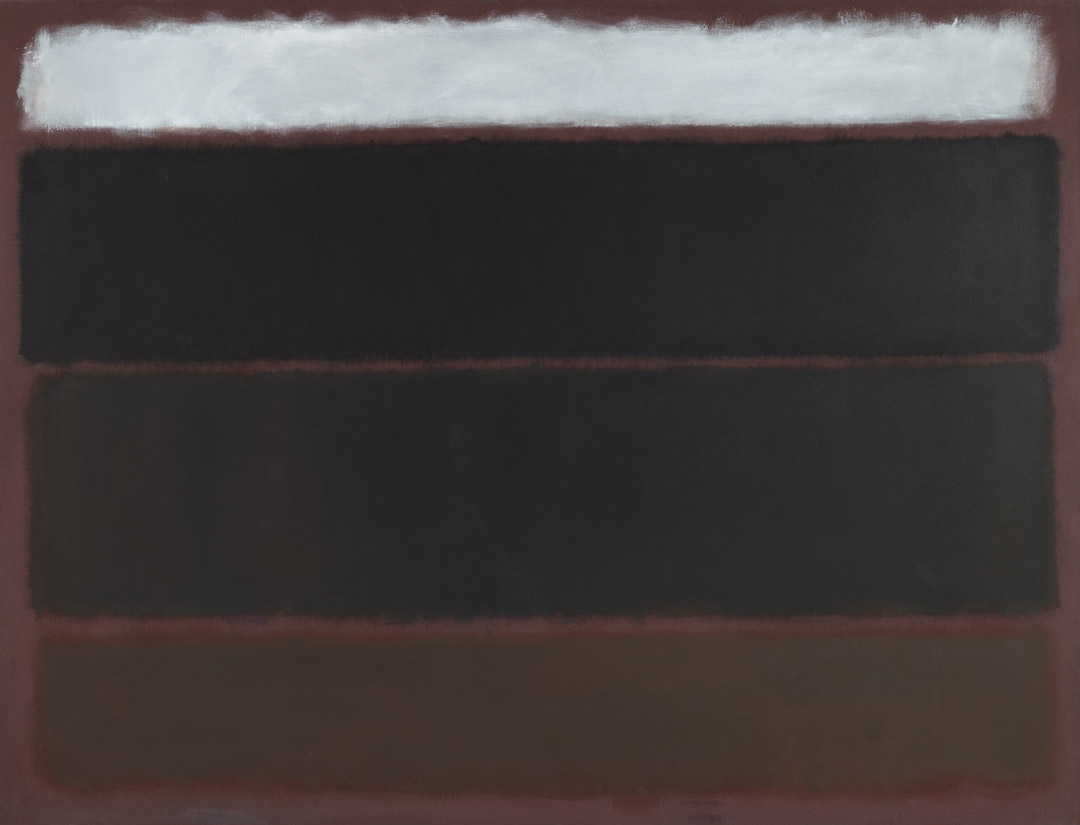

Robert Motherwell, Before the Day, 1972

Acquired October 12, 1972

Adolph Gottlieb, Crimson Spinning #2, 1959

Acquired December 11, 1972

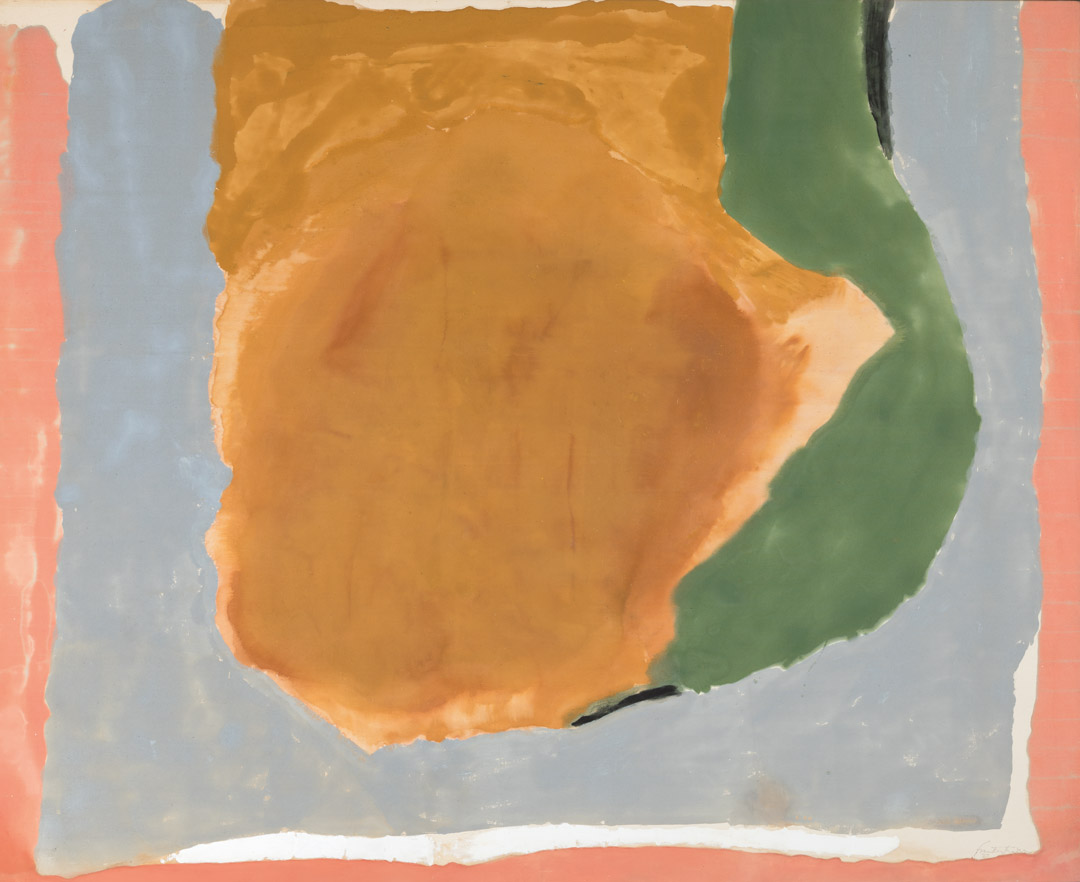

Helen Frankenthaler, Dawn Shapes, 1967

Acquired April 26, 1973

Clyfford Still, PH-338, 1949

Acquired November 10, 1973

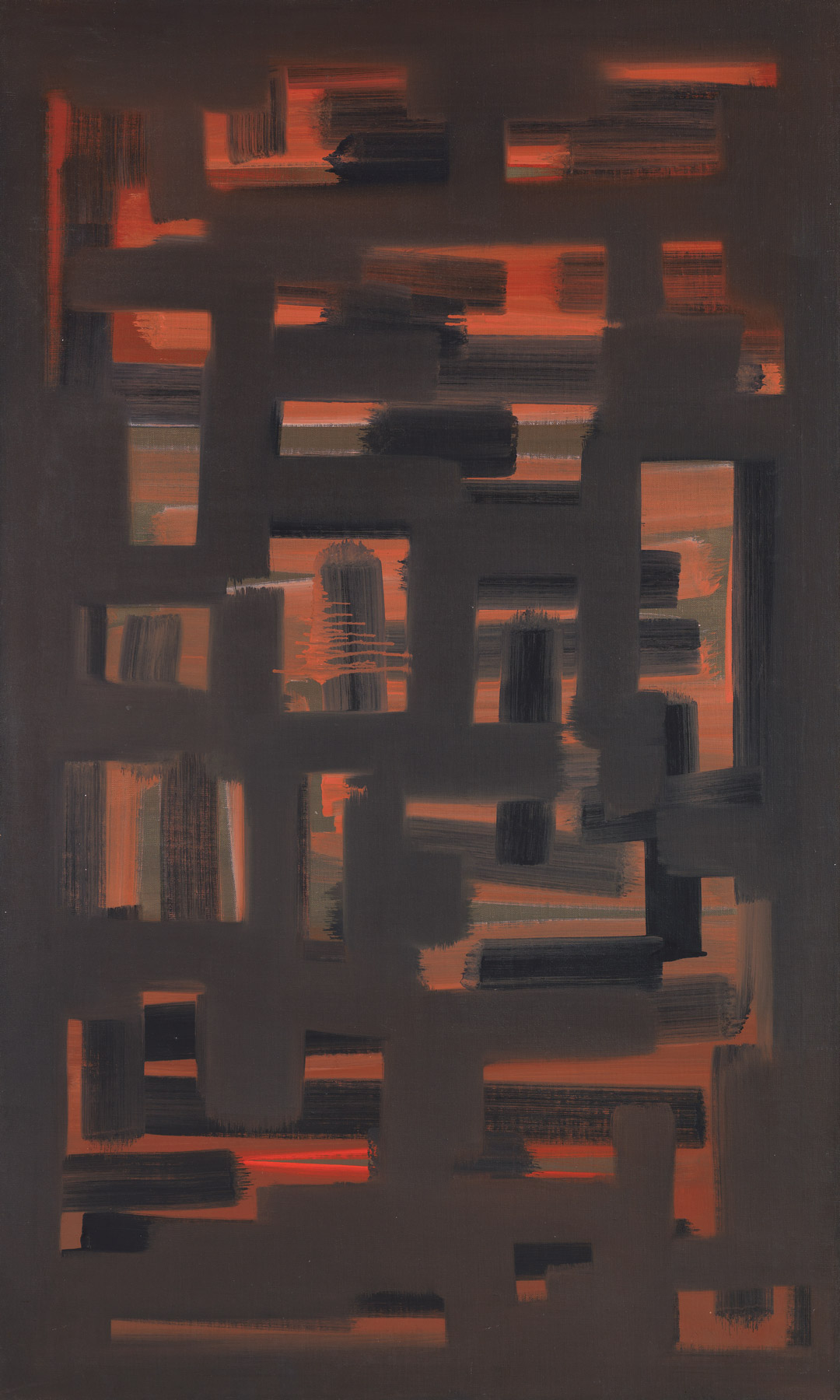

Ad Reinhardt, Painting, 1950, 1950

Acquired January 8, 1974

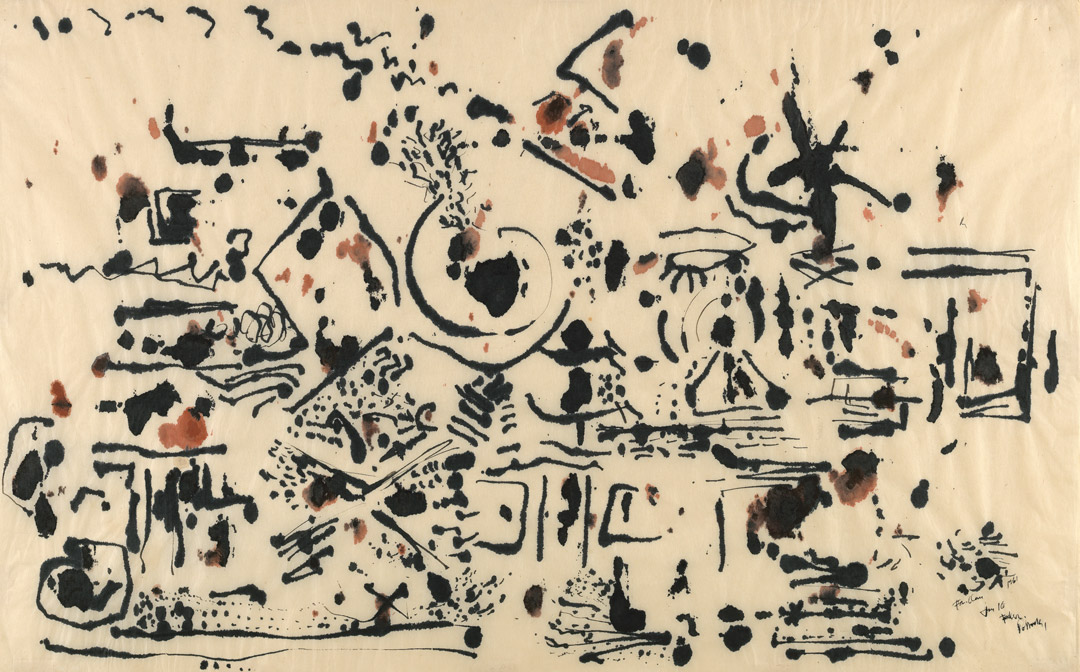

Jackson Pollock, Untitled, 1951

Acquired March 29, 1974

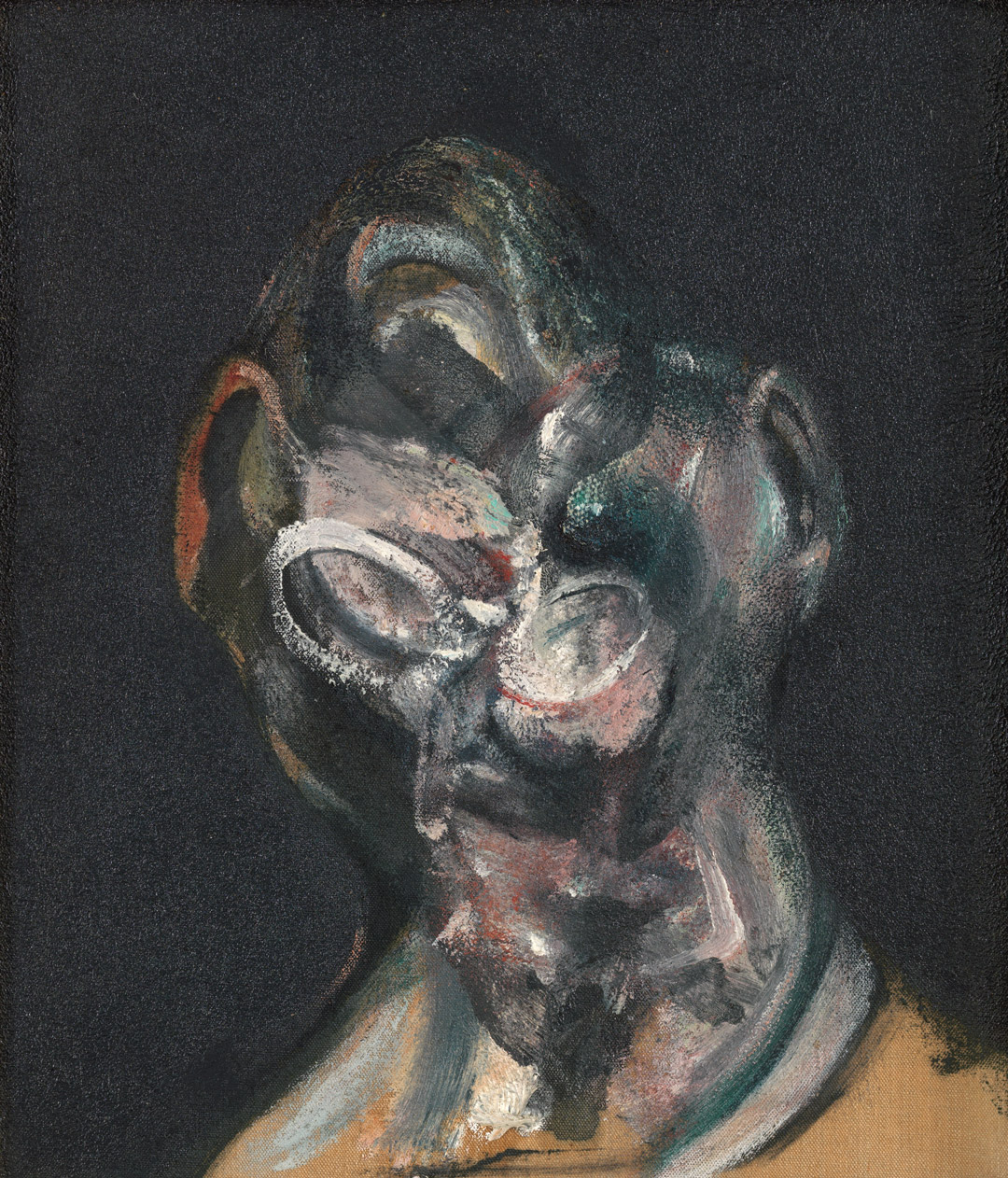

Francis Bacon, Portrait of Man with Glasses I, 1963

Acquired October 24, 1974

Alberto Giacometti, Femme de Venise II, 1956

Acquired January 2, 1975

Robert Motherwell, Irish Elegy, 1965

Acquired November 7, 1975

Francis Bacon, Study for a Portrait, 1967

Acquired November 20, 1976

Willem de Kooning, Town Square, 1948

Acquired December 6, 1976

Joan Mitchell, The Sink, 1956

Acquired September 12, 1977

David Smith, Cubi XXV, 1965

Acquired February 22, 1978

Philip Guston, To B.W.T., 1952

Acquired February 14, 1979

Mark Rothko, Untitled, ca.1945

Acquired November 12, 1980

Lee Krasner, Night Watch, 1960

Acquired November 19, 1981

Philip Guston, The Painter, 1976

Acquired February 1, 1982