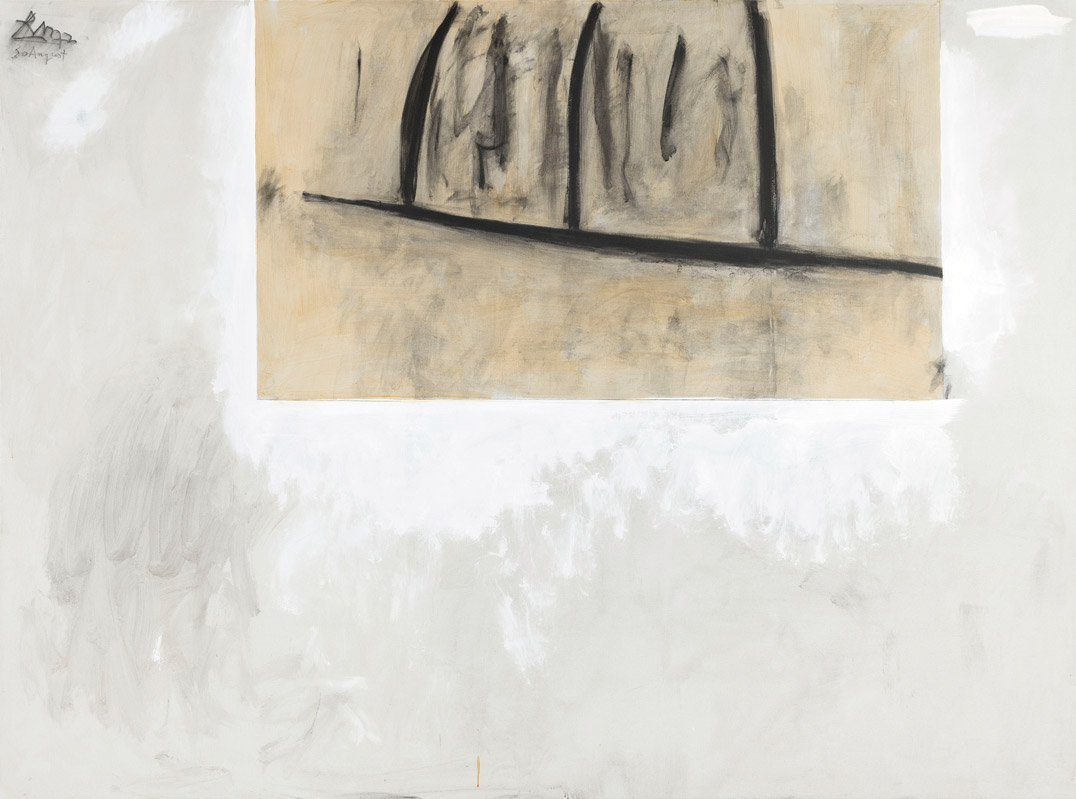

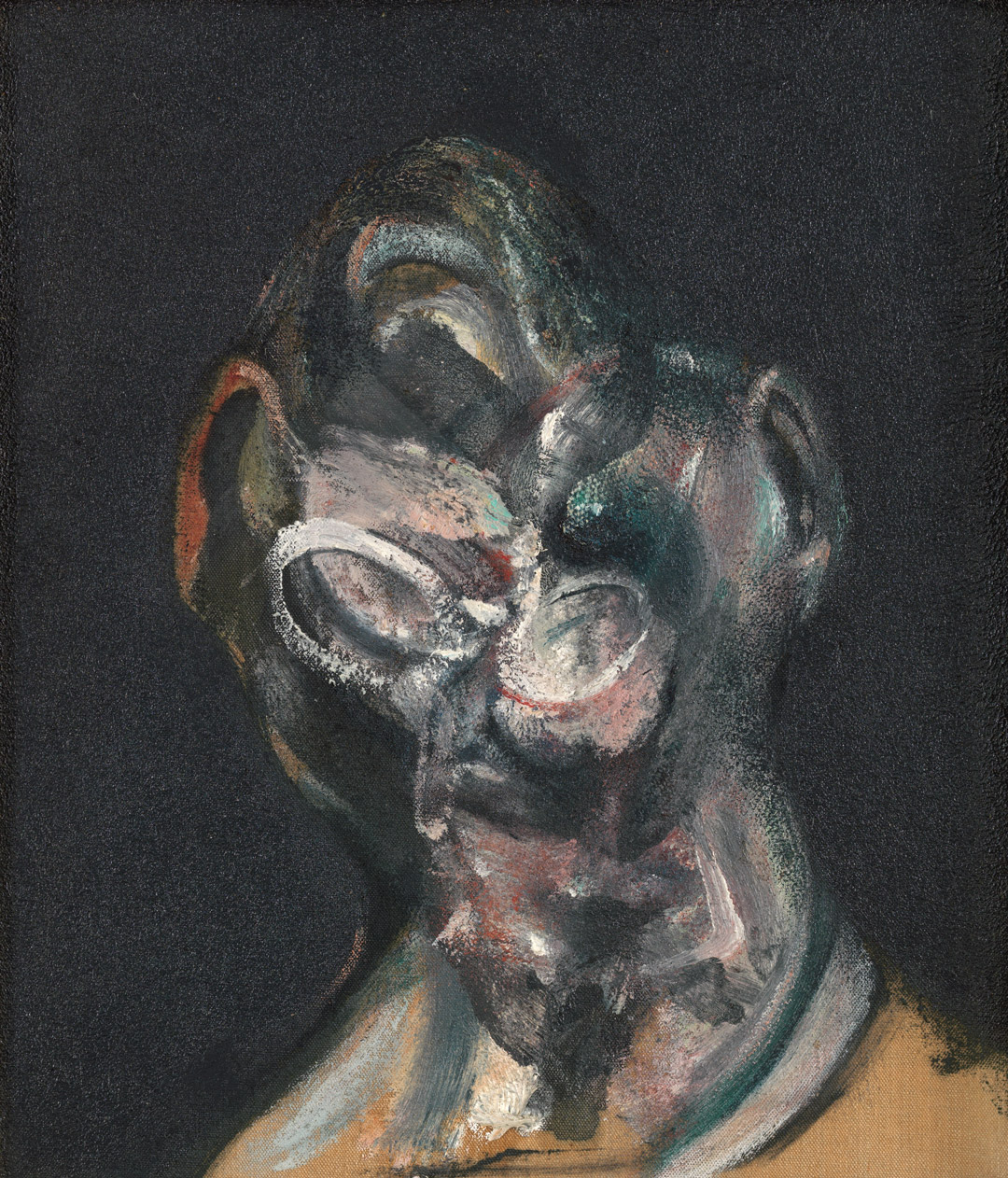

Study for a Portrait

1967 [67-11]

Francis Bacon

British, born Ireland (1909–1992), oil on canvas, 61 x 55 in. (155 x139.8 cm). Seattle Art Museum, Gift of the Friday Foundation in honor of Richard E. Lang and Jane Lang Davis, 2020.14.7. Photo by Spike Mafford / Zocalo Studios. Courtesy of Friday Foundation. © 2021 The Francis Bacon Estate / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Study for a Portrait

Martin Harrison

Francis Bacon painted Study for a Portrait (1967) midway between two major solo exhibitions: a 1962 retrospective at the Tate Gallery, London, and a 1971 exhibition at the Grand Palais, Paris. The Tate exhibition had focused Bacon’s attention on his art with a new urgency after his production in the years since 1957 had grown scattered, haphazard, and intermittent. As the exhibition deadline loomed, its importance appears to have registered with him. It became the catalyst for rethinking his artistic practice, as his Grand Palais exhibition would the following decade; moreover, the external stimuli of these prestigious retrospectives helped overcome a perpetual problem—his psychological resistance toward facing the challenge of the bare canvas on his easel. Singular in a number of ways, Study for a Portrait belongs to that period of renewed productivity.

One consequence of the Tate retrospective was that Bacon began to simplify the formats of his paintings. Thereafter, they conformed, almost invariably, to one of two dimensions: the small portraits on 14 × 12–inch canvases, like Portrait of Man with Glasses I (1963), and the large “subject” paintings measuring 78 × 58 inches. At 61 × 55 inches, the Lang Collection Study for a Portrait does not, of course, fit in either category. As such, it may be regarded as a pendant to the almost identically sized painting Bacon had completed shortly before it, Two Figures on a Couch (1967, Private Collection); the latter was his first painting since 1954 to depict coupling males. A plausible explanation for the unusual format of the two paintings is that they were painted not in London but in the studio of his friend Denis Wirth Miller, at Wivenhoe, Essex, which Bacon used frequently at this time and in which his usual 78-inch canvases would have been cumbersomely large and an imposition on his friend’s space.

The sitter in Bacon’s Study for a Portrait, who has sometimes been identified as the artist Isabel Rawsthorne, is, in fact, Henrietta Moraes. Bacon was a close friend of both women, but he made a sharp distinction between their respective roles in his paintings. All of his paintings of female nudes after 1962 were based on photographs of Moraes, whereas Rawsthorne never appeared in nude depictions, only in portraits. In the 1950s, Moraes had worked occasionally as an artists’ model, notably for Lucian Freud. Bacon commissioned John Deakin to take the nude photographs of her that provided the body positions for most of the female nudes that he painted between 1961 and 1972. Rawsthorne had inspired Jacob Epstein, André Derain, Pablo Picasso, and Alberto Giacometti in the 1930s, which no doubt held a fascination for Bacon, but it played no part in his painting practice, and she never sat for his nude females. Irrespective of Bacon’s friendship with Moraes, his most extreme depictions of women as viragos or termagants were exclusively of her or, it should be said, began with her.

Study for a Portrait is unique in Bacon’s oeuvre. From 1948 onward, he tended to work sequentially and self-referentially. Consider his reworkings of themes such as the Popes, crouching figures or lying figures, which should be seen as striving for refinement—a clearer explication of his first idea—rather than mere repetition. But the configuration of Study for a Portrait, like that of Landscape near Malabata, Tangier (1963, Private Collection) and Three Studies from the Human Body (1967, Private Collection), was never repeated, and was perhaps considered by Bacon too completely resolved to lend itself to replication. Nonetheless, certain elements of the composition had been present in Bacon’s work for several years. For example, the first nude painted from John Deakin’s photographs, Crouching Nude (1961, Private Collection), acted as a springboard for other nudes, both female and male, including Study for a Portrait, in which Bacon’s distortions, the “additional” or superfluous limbs, verged on the anatomically ludicrous.

When embarking on Study for a Portrait, Bacon must have had in mind, in addition to Robert Yerkes’s chimpanzees and possibly Joan Miró’s Seated Woman (October 1932, Private Collection), the attenuated, exaggerated limbs of Henri Matisse’s sculpture La Serpentine (1909, fig. 1). Matisse’s initial reliance on a photograph (now in the Archives Matisse, Paris) when making the bronze was a rehearsal of Bacon’s practice. In addition to the extreme sinuousness of the body, there are specific correspondences in the crooked elbow on which the women in both works lean as well as the legs crossed just above the ankles. The classically posed, raised, arched arm, found in many of Matisse’s odalisques, is developed into Moraes’s anatomically impossible elongated limb in Study for a Portrait. The crouching figures that became an obsessive theme of Bacon’s from 1952 were similarly indebted to the left-hand figure in Matisse’s Bathers with a Turtle (1908, St. Louis Art Museum). Such appropriations are apparently at odds with Bacon’s denials of Matisse’s importance for him, his typically bipartite assessment that he lacked Picasso’s “brutality of fact,” but Bacon probably considered the co-opting of a body position as fundamentally different from being inspired by the core of another artist’s practice.

The sofa on which Moraes reclines is virtually a sofa-bed. Bacon had been painting these enveloping couches since 1962, and in the context of his own spartan, unheimlich living quarters, the luxury and comfort they convey may seem paradoxical; Bacon, though, partly cancels out the comfort by perching Moraes uneasily on her support, like the Oceanid nymph Perseis about to be consumed by waves. The incorporation of a patch of Aubusson carpet at the lower right functions to indicate that the room has a curved rear wall. Bacon firmly resisted linking elements of his paintings with his autobiography, yet he proposed to interviewers that these spaces may have been spurred by memories of the curved bays in his grandmother’s house in County Laois, Ireland, where he had stayed as a child. Traditional perspective was irrelevant to Bacon, and instead his figures occupy liminal zones—sometimes claustrophobic or, as in Study for a Portrait, thrusting the figure toward the spectator.

The device of reproducing three of his earlier paintings, pinned to the rear wall, occurs nowhere else in Bacon’s oeuvre. The image on the right refers to the right panel of Three Studies for a Crucifixion (1962, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum), and the central image closely resembles Seated Figure (1962, Private Collection); the latter painting incorporated an early version of the enveloping sofa that dominates Study for a Portrait. The image on the left, bisected by the picture’s edge, is executed with an expressionist abandon that cannot be compared with any of Bacon’s paintings, unless it refers, inexplicably, to one of his earliest works, Composition (1933, Henry Moore Family Collection). The incorporation of the device may have been suggested by the reproductions of his own work that Bacon habitually stuck to the walls of the kitchen/bathroom area of his living quarters at 7 Reece Mews, as well as in his studio. It was a common enough motif in the paintings of many artists Bacon admired, and he may have had in mind, for example, Édouard Manet’s dramatic portraits of Berthe Morisot, La Repose (1870, Rhode Island School of Design), on a sofa, and Le Suicidé (1877–81, Fondation E. G. Bührle), on a bed. In Manet’s Portrait of Emile Zola (1868, Musée d’Orsay), the three prints on the rear wall include the artist’s own Olympia, a self-referencing akin to that Bacon employed in Study for a Portrait.1

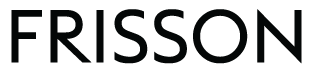

Bacon first appropriated the African mask aspect of the heads of the women in Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907, Museum of Modern Art, New York) in his Study for Portrait of P.L. (1962, Private Collection). Umberto Boccioni’s futurist distortions, seen in both his sculptures and paintings, such as Dynamism of a Man’s Head (1913, Private Collection), may also have been at play with Bacon. In the present painting, Moraes’s head was further modified by a still frame from Alain Resnais’s film Hiroshima mon amour (1959). The image that resonated with Bacon, and which he conflated with Picasso’s demoiselles, was from the shower scene featuring the film’s costars, Eiji Okada and Emmanuelle Riva. Many illustrated books were devoted to this influential classic of French New Wave cinema, and in their reductive half-tone reproductions, Riva’s teeth closely resemble those of Moraes in Bacon’s painting. One of these images (now in the Hugh Lane Gallery) was found in Bacon’s studio; it is paint spattered, folded, and paper-clipped onto cardboard, evidence of his repeated usage (fig. 2). Bacon turned Riva’s smile into a sinister, predatory snarl, a signifier, perhaps, of his ambivalence toward female sexuality. The strands of wet hair falling over Riva’s face, closely replicated in Bacon’s small portrait Study of Henrietta Moraes (1969, Private Collection), are rendered more obliquely in Study for a Portrait, with what was becoming, by that time, a Bacon trope: a spurt of thick white oil paint.

What, then, are we to make of Bacon’s appropriations from Matisse and Picasso? There was probably an element of high-level, art historical sanction in Bacon’s modus operandi, which also permitted him to steal from any images he chose, selecting them at will as components he sought to reconfigure and transcend in the act of painting. Of the less-elevated sources that came into play, the exposed bone structure of Moraes’s legs in Study for a Portrait depended on photographs in K. C. Clark’s Positioning in Radiography, a book Bacon consulted frequently, attracted by its potent mix of scientific detachment and the reduction of humans to flesh, or meat. I have referred to Study for a Portrait as a nude depiction, but seminude is more accurate, for Moraes is wearing what may be an item of black lingerie, or a bathing top. Bacon painted four more female nudes through 1972, but ceased to do so subsequently, with the exception of the almost caricatural Sphinx—Portrait of Muriel Belcher, in 1979 (Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo). The kind of V-shape formed by two thinned black strokes across Moraes’s lower body was a recurrent motif in the 1960s that Bacon employed to denote, cursorily, a figure’s sex, or possibly stocking-tops or suspenders, both of which he wore as sexual attractants. Thus, Bacon’s dual gender identification becomes another motivational impulse for the painting.

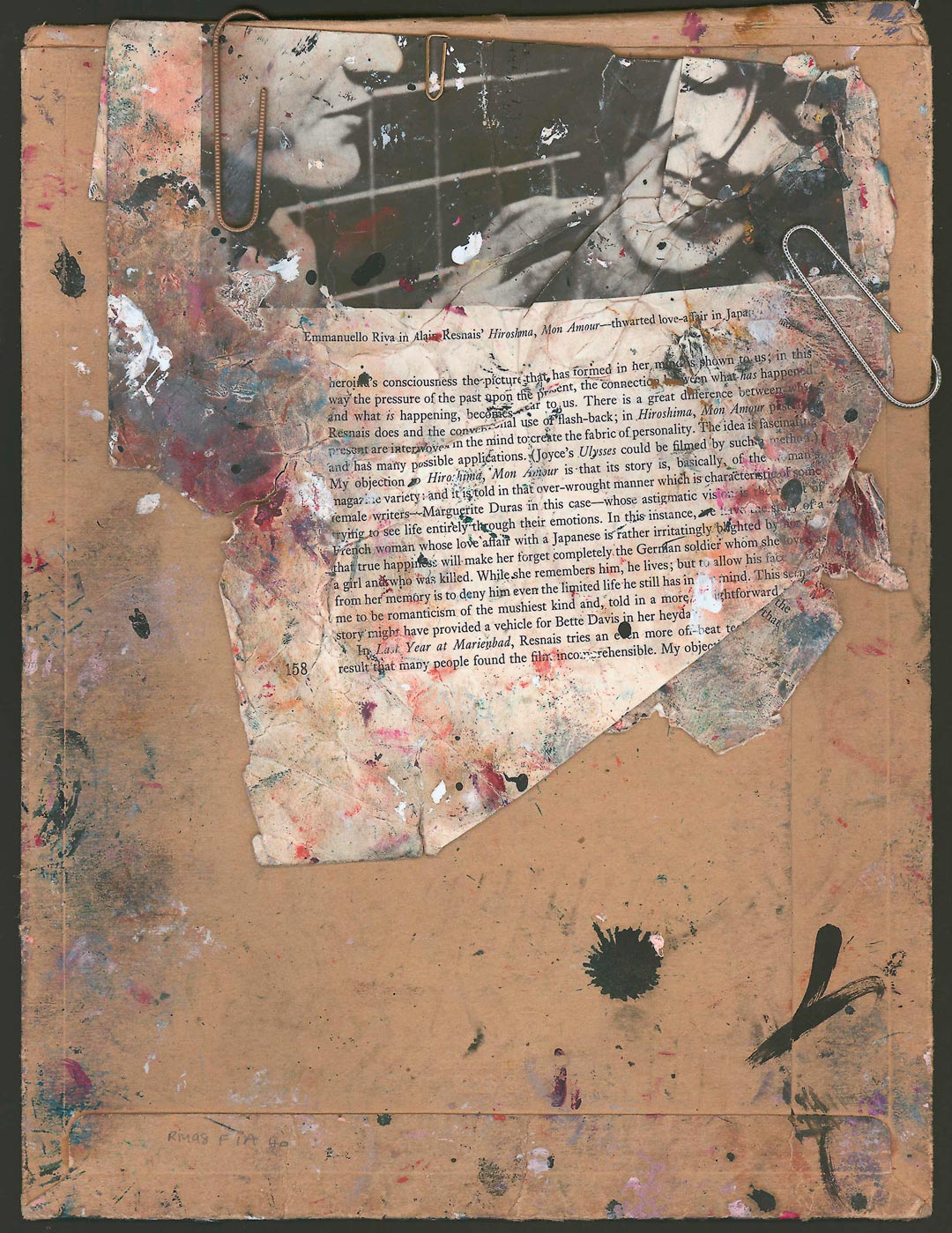

Study for a Portrait was delivered with the paint still wet to Marlborough Gallery, London, in July 1967. There is no particular explanation for the apparent urgency, although the gallery was always anxious to get paintings out of Bacon’s studio before he reconsidered and destroyed them. Bacon was adamant that his paintings should be framed under glass, not so much to protect their (stable) oil surfaces, but because he wanted the painted image to be seen in conjunction with the reflections in the glass—a simultaneous presenting and withdrawing that points to his complex psychological motives. Interestingly, his instructions on the Lang Collection canvas’s stretcher confirm this insistence (fig. 3). Study for a Portrait was first exhibited in the sixth John Moores exhibition at the Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool, in November 1967, but as an hors concours work it did not have to be submitted to the selection committee. The first prize in that exhibition was awarded to David Hockney’s Peter Getting Out of Nick’s Pool (1966, Walker Art Gallery). In his breakthrough years at the Royal College of Art, Hockney had been inspired by Bacon’s example, both by the male-orientated subject matter and by his brusque painting technique. After Hockney moved to Los Angeles in 1964, his paintings became more vivid in color and their compositions pared down. Bacon, too, was simplifying his pictorial formats, employing household (alkyd) paints for the flattened planes of his grounds, rather than the acrylics used by Hockney; these were almost invariably added after the figure had been laid down, and frequently modified after “completion.”

In the Portrait of Man with Glasses series painted in the early 1960s, Bacon had not entirely emerged from the “black cavern” of the previous decade, whereas the brighter blue and yellow palette of Study for a Portrait is comparable with Hockney’s swimming-pool paintings. That Bacon was paying attention to British Pop Art and American Abstract Expressionism is often overlooked, but it is a topic that warrants closer study. Study for a Portrait was, then, an important marker of the modernizing agenda that increasingly distinguished Bacon’s paintings in the last twenty-five years of his life. With gestural, malerisch intensity now reserved for the essence of the image—the head, or selected parts of the body—the greater economy of his “very clear”2 backgrounds reflects his striving for, as he put it, the immaculate.

Author

Martin Harrison has been writing about Francis Bacon since 1999 and edited Francis Bacon: Catalogue Raisonné (2016), published by the Estate of Francis Bacon, where he is head of publishing. He coauthored the fourth volume in the series Francis Bacon Studies, Francis Bacon: Shadows (Thames and Hudson, 2021).

Notes

1 I wish to thank Catharina Manchanda for the conversation in which she raised the question of the Zola portrait, which I might otherwise have forgotten.

2 David Sylvester, The Brutality of Fact: Interviews with Francis Bacon (London: Thames and Hudson, 1997), 120.

Explore the Collection

Sort by Chronology

Sort by Artist

Sort by Author

Franz Kline, Painting No. 11, 1951

Acquired November 13, 1970

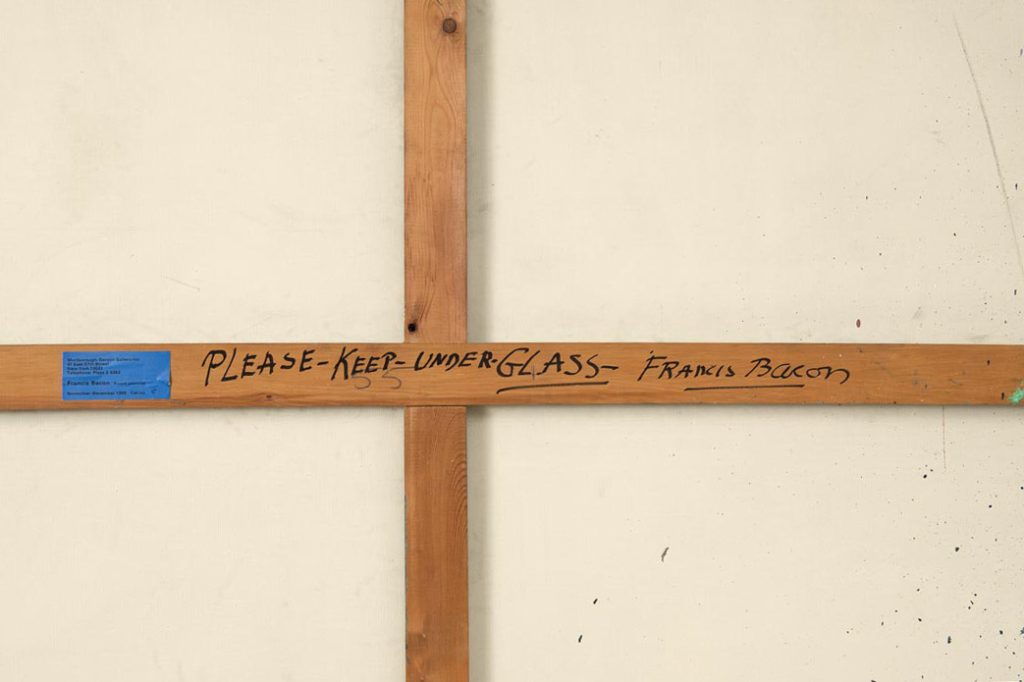

Mark Rothko, Untitled, 1963

Acquired May 18, 1972

Robert Motherwell, Before the Day, 1972

Acquired October 12, 1972

Adolph Gottlieb, Crimson Spinning #2, 1959

Acquired December 11, 1972

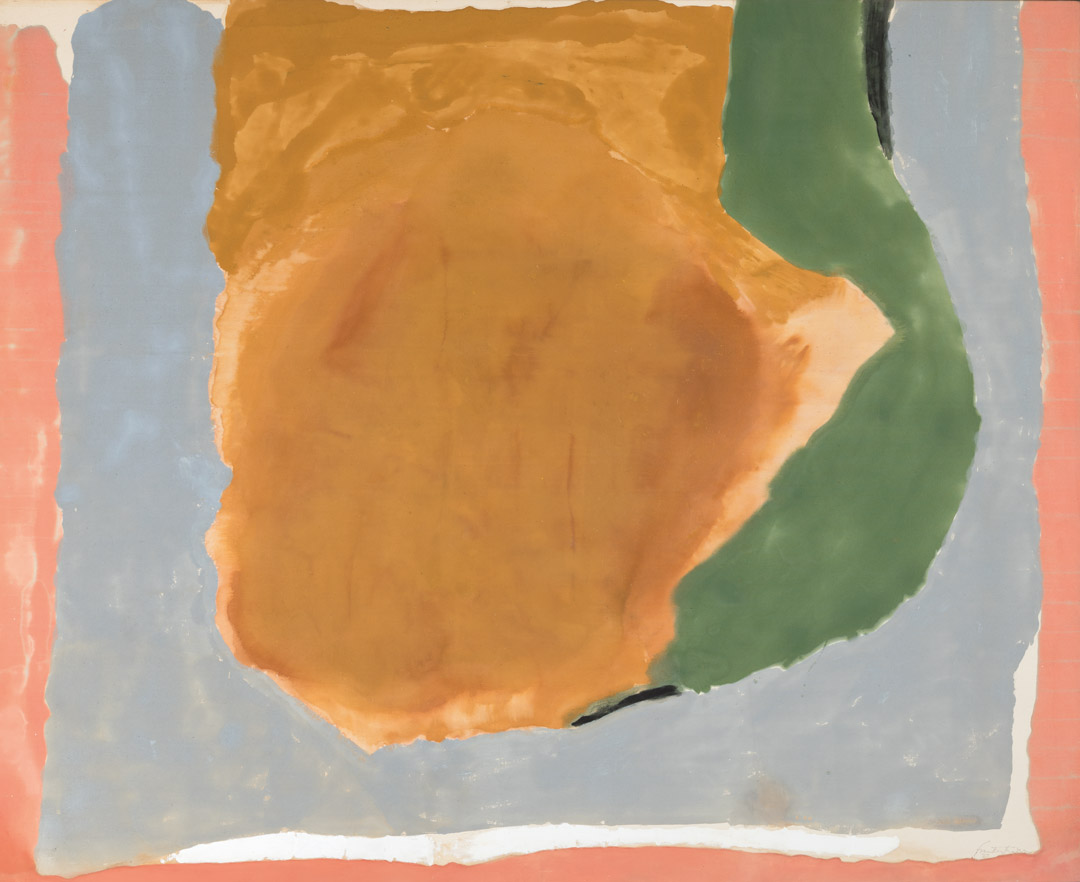

Helen Frankenthaler, Dawn Shapes, 1967

Acquired April 26, 1973

Clyfford Still, PH-338, 1949

Acquired November 10, 1973

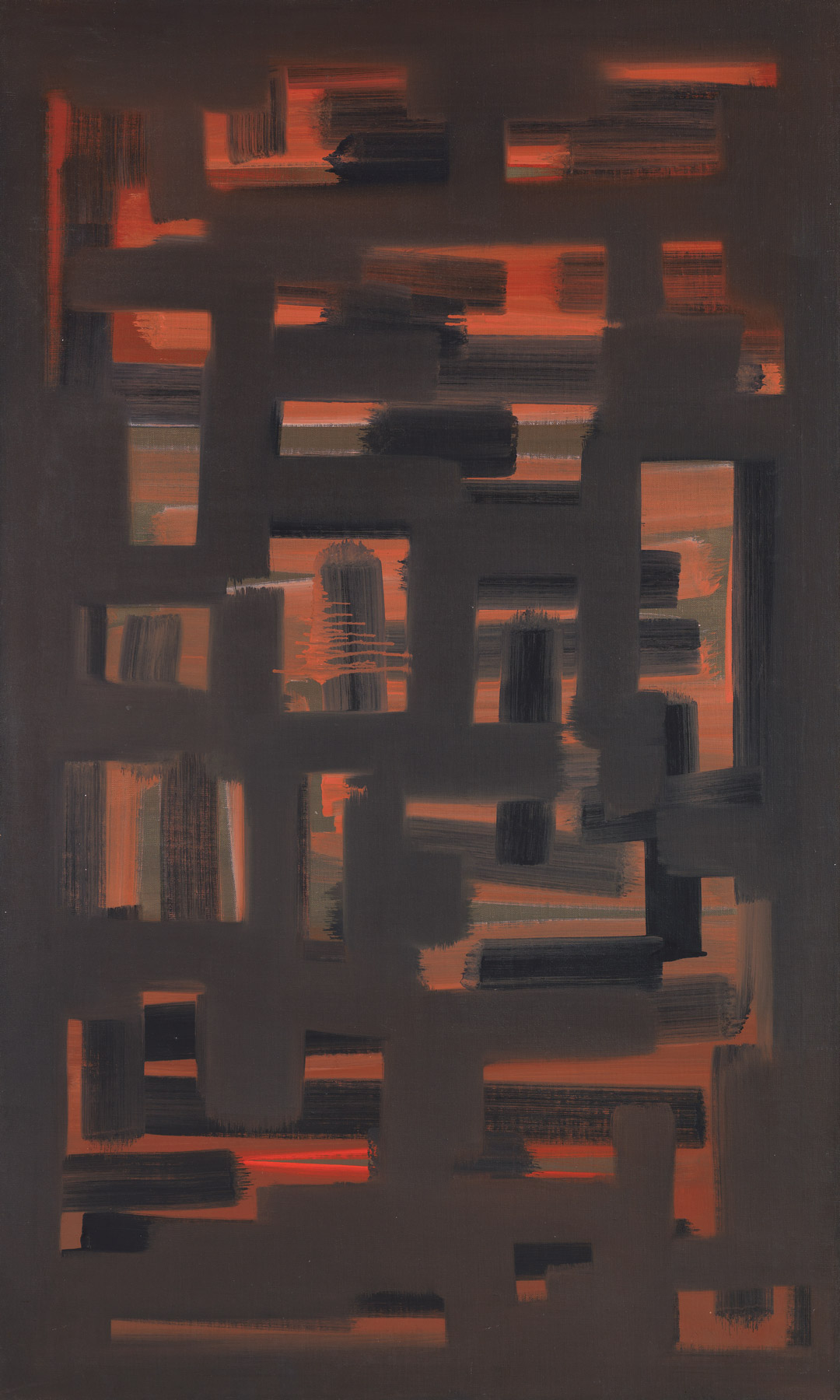

Ad Reinhardt, Painting, 1950, 1950

Acquired January 8, 1974

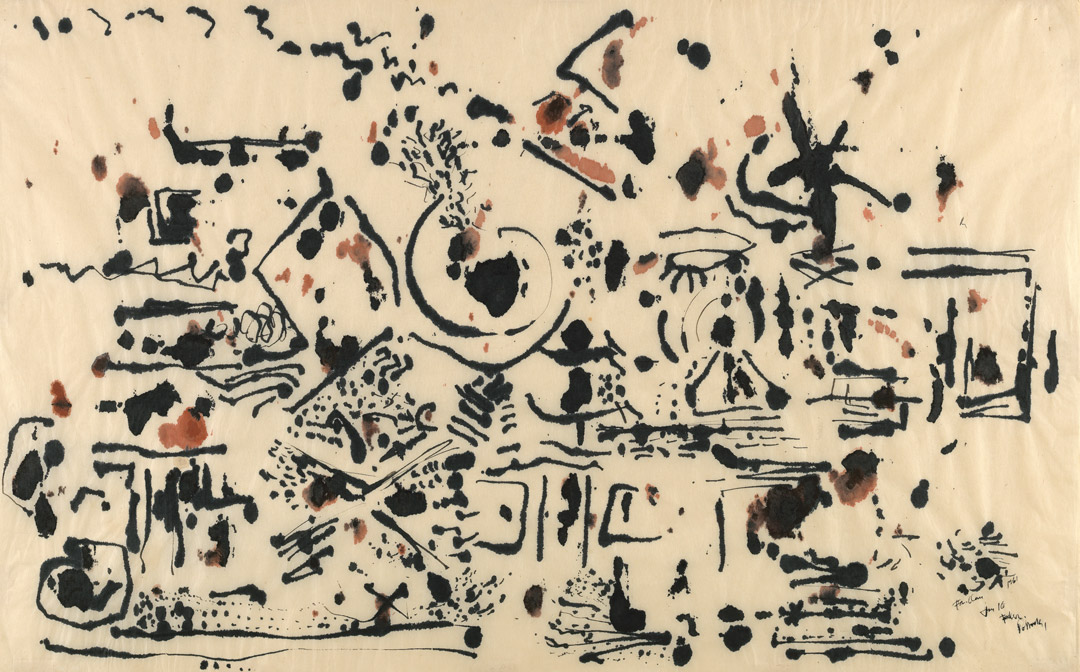

Jackson Pollock, Untitled, 1951

Acquired March 29, 1974

Francis Bacon, Portrait of Man with Glasses I, 1963

Acquired October 24, 1974

Alberto Giacometti, Femme de Venise II, 1956

Acquired January 2, 1975

Robert Motherwell, Irish Elegy, 1965

Acquired November 7, 1975

Francis Bacon, Study for a Portrait, 1967

Acquired November 20, 1976

Willem de Kooning, Town Square, 1948

Acquired December 6, 1976

Joan Mitchell, The Sink, 1956

Acquired September 12, 1977

David Smith, Cubi XXV, 1965

Acquired February 22, 1978

Philip Guston, To B.W.T., 1952

Acquired February 14, 1979

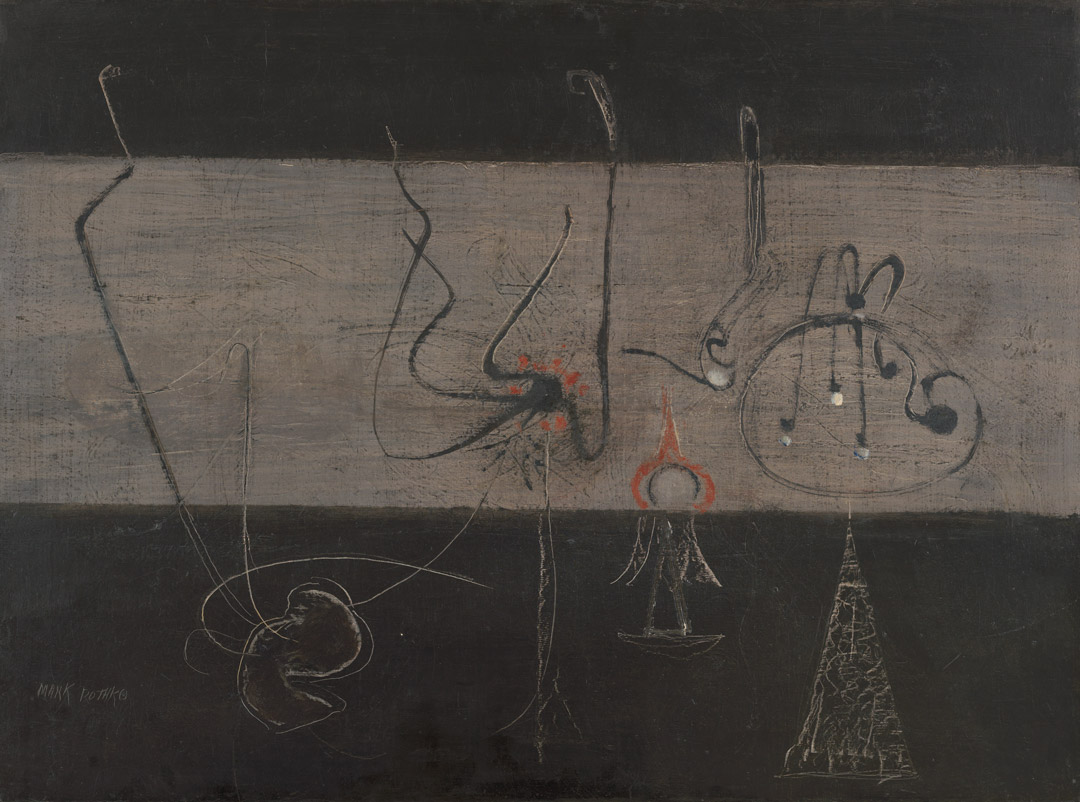

Mark Rothko, Untitled, ca.1945

Acquired November 12, 1980

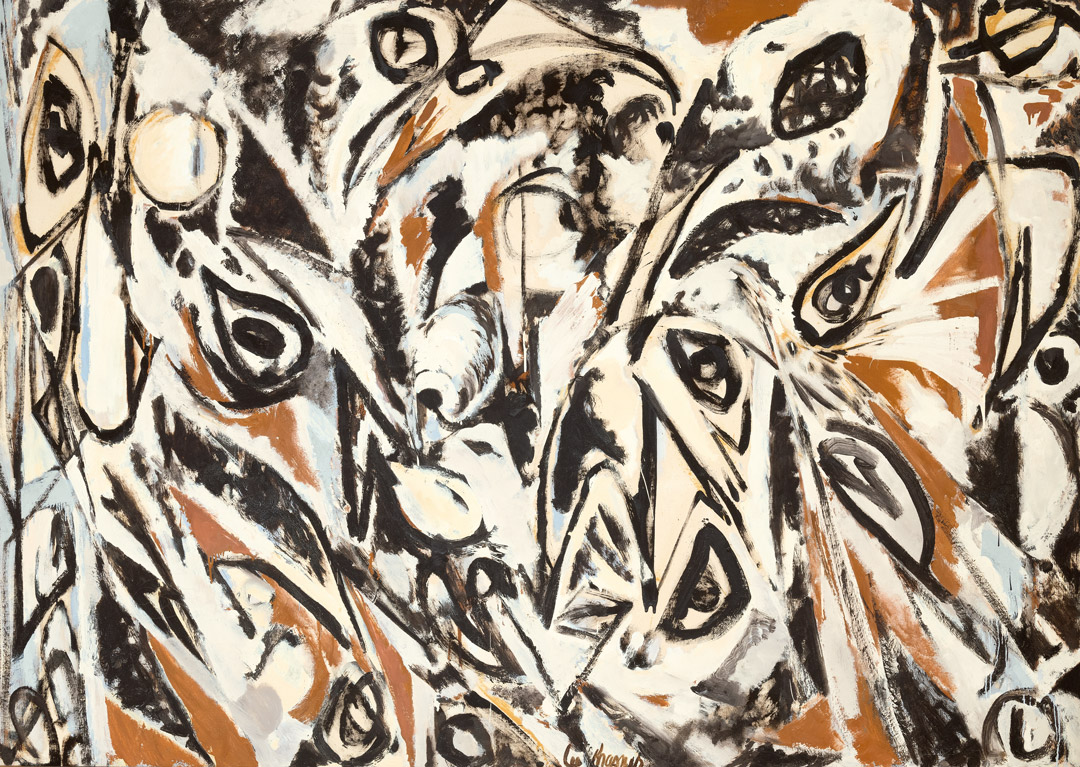

Lee Krasner, Night Watch, 1960

Acquired November 19, 1981

Philip Guston, The Painter, 1976

Acquired February 1, 1982