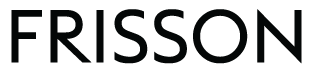

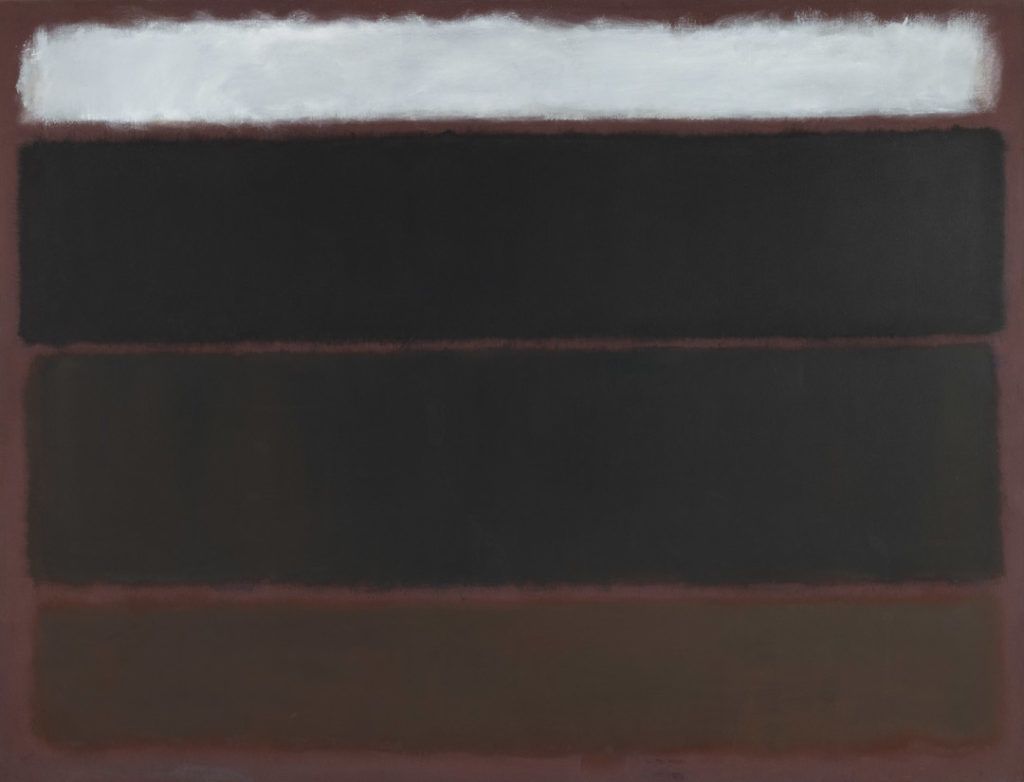

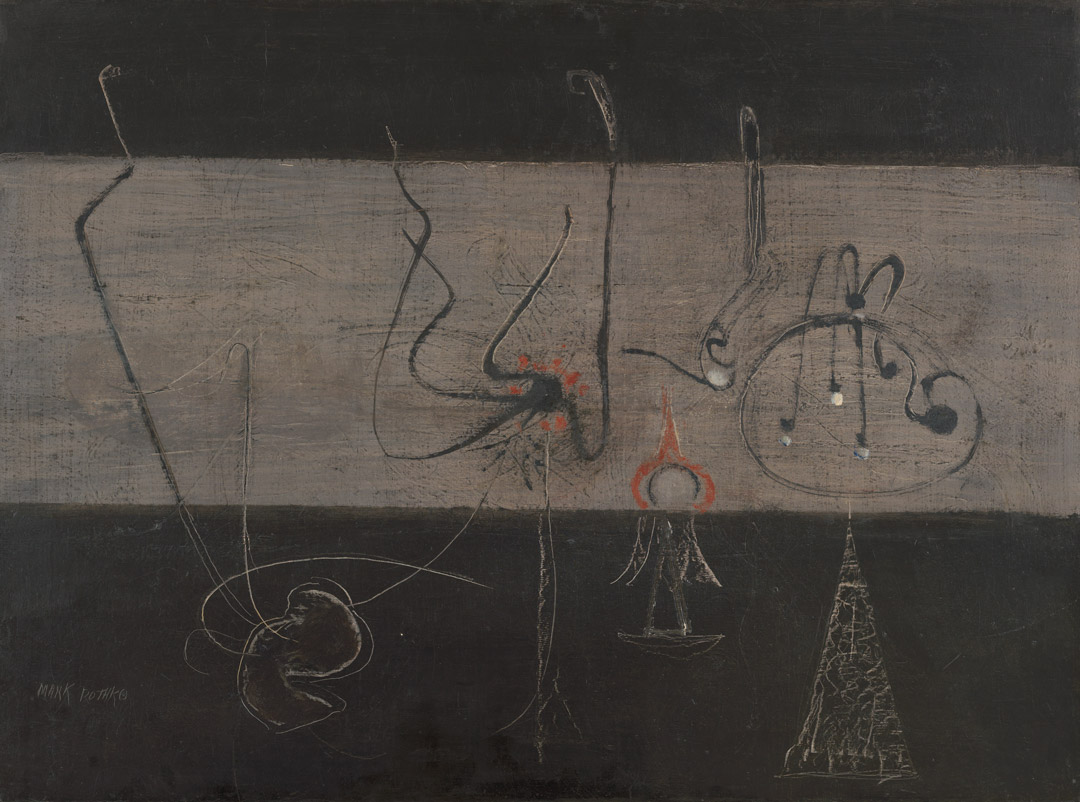

Untitled

1963

Mark Rothko

Oil on canvas, 69 × 90 in. (152.4 × 228.6 cm). Seattle Art Museum, Gift of the Friday Foundation in honor of Richard E. Lang and Jane Lang Davis, 2020.14.16. Photo by Spike Mafford / Zocalo Studios. Courtesy of Friday Foundation. © 2021 The Mark Rothko Estate / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Untitled

Jeffrey Weiss

Our first impression of the Lang Collection’s 1963 painting by Mark Rothko is apt to be one of value and scale. A white bar emblazoned in the work’s upper reaches intensifies its dark palette. Below, three elongated, narrowly separated forms spread across a horizontal field that they redouble and almost fill—the composition is at once expansive and constrained. Yet, moving close to the painting, we see an unexpected detail: flecks of white so small and scattered they can only be detected from within several feet of the canvas. Paint flecks of this kind occur throughout Rothko’s work of the 1950s and early 1960s; they are generally accidental, the residue of process (rather than having been produced by deliberate, well-aimed flicks of the brush). Rothko used thinned paint, drops of which can fly off the bristles when, on being dipped, the brush is waved in front of the painting before landing to make a mark. The dimensions of the canvases were such that he worked as much from the shoulder as from the elbow and wrist. Elsewhere in Rothko’s works on canvas we also often detect running rivulets or drips.

The process of the work is thus exposed.1 It is important to acknowledge that the artist’s painterly finesse does not represent a polished refinement—the kind of fastidiousness that might be attributed to the work were we to know it only through reproductions in books. Rothko did not speak much of process in this way, but the signs of it are clear, and they ask to be accounted for. A sensation of breadth is partly attained through the layered application of thin veils of paint that lightly hold the feathered gestures of the brush. A certain loose immediacy obtains. As the paintings are sized but not primed, paint both saturates the canvas and sits on its surface. In the course of making the work, other things happen—the flecks, the drips—that, although unplanned, are accepted by the artist as wholly in keeping with the material character of the painting overall.

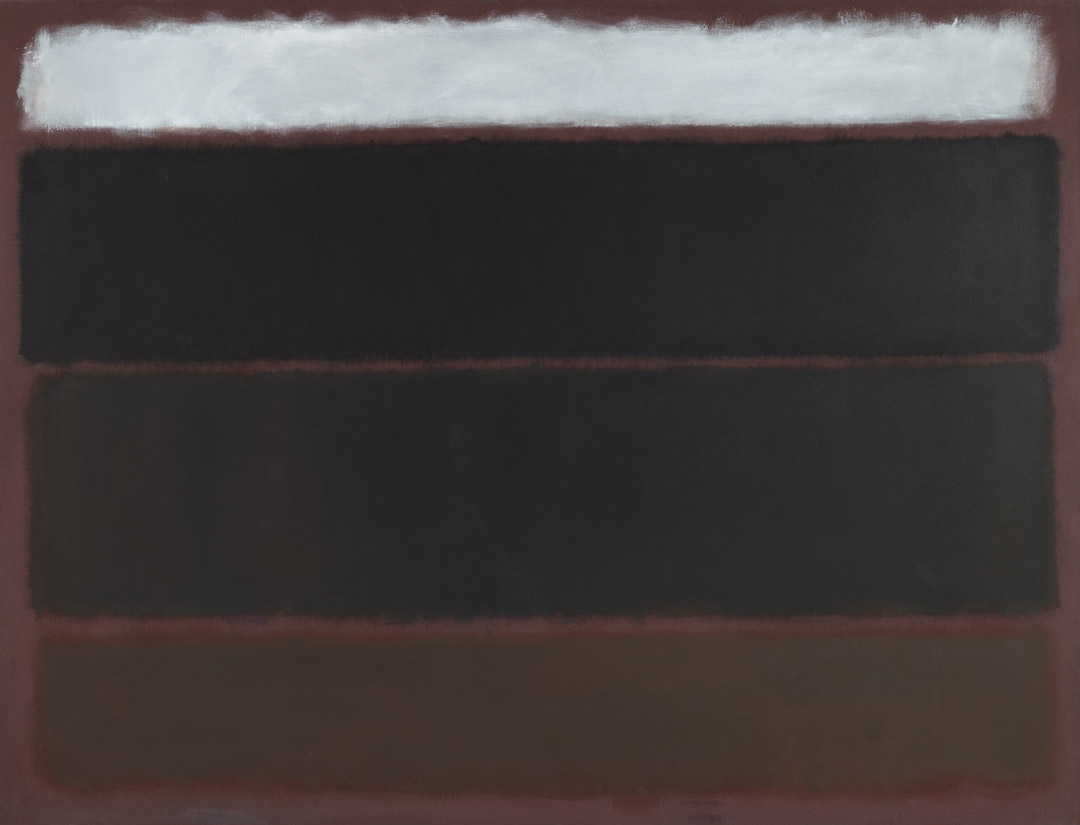

As David Anfam, author of the catalogue raisonné of Rothko’s paintings, has fully discussed, the period of roughly 1958 to 1966 in Rothko’s work was dominated by mural commissions: the Seagram murals (1958–62), the Harvard murals (1962–64), and his works for the Rothko Chapel in Houston (1965–66). Anfam identifies paintings produced independently of these projects as having been closely related in palette and, in some cases, structure to the murals, which were the object of intensive campaigns of work. Accordingly, the Lang Collection painting falls within what Anfam refers to as the period of the Harvard murals and related works.2 Paintings for the Harvard mural project were distinguished by a palette of dark reds and plummy browns as well as deep blues and reddish, greenish, and bluish grays, a narrow range of hue and value that matches that of the Lang Collection painting. That said, Rothko introduced that palette during the late fifties, around the time of his work on the Seagram commission (fig. 1).

Moreover, like a number of other works of 1963 and 1964, the Lang Collection painting closely anticipates the even darker cast of the Houston murals, with their repertoire of near-black colors that have long been said to defy the specificity of a conventional name. In sum, the last ten or twelve years of Rothko’s production, within which the Lang painting falls, demonstrate various kinds of darkness that came increasingly to prevail.

In form, the Lang Collection painting bears no resemblance to the Harvard mural paintings, which were constructed as a friezelike arrangement of notched frames that expand and contract from one image to the next, a device that Rothko extrapolated from his work on the Seagram commission. Yet, while its “stacked” arrange-ment of forms follows the by-then classic configuration of Rothko’s work since 1950, the large horizontal format of the Lang Collection painting—which he had employed only around a half-dozen times prior to embarking on the Seagram commission—might be said to respond directly to the wide-format nature of the murals. As Dore Ashton first observed, the very idea of mural painting supports Rothko’s ambition for his work in general: to produce a kind of painting that rewards the close proximity of the beholder with a visual immersion. For this reason, Rothko preferred not to exhibit in the company of others, and was given to installing his paintings close together.3 The artist said that crowding in this way subordinates the wall to the surface of the paintings.4 The large horizontal-format painting is related to this idea: “The best way I can involve the viewer,” Rothko said to the curator Katherine Kuh, “is to make the painting so big that he can’t absorb it in one easy glance. He has to be enveloped by the painting. He has to be able to see it by turning in space.”5

Yet we should not forget that while Rothko’s nonmural paintings are autonomous works, they often also share features with other paintings, as if they loosely belong to sets, sequences, or groups. While not systematic, such resemblances allow us to observe the artist investigating variants of specific combinations of color and form. For example, we note that the distribution of dark colors with a single white form in the Lang Collection painting closely corresponds to various works of this period in which the white area changes position—top, middle, bottom—within a field that is otherwise dark. One such painting, the much larger, horizontal-format No. 9 (White and Black on Wine) of 1958 (Glenstone), may have been painted as a possible Seagram mural panel (before Rothko developed a new image for the commission). Another work, Untitled (Black, White, Grays on Maroon) (1963, fig. 52), is vertical in format but identical in size to the Lang painting. Here, the matching dimensions—as if the same canvas had been rotated a single turn—expose a pictorial thought process that is, at least in part, analytical. In other words, while we often speak of Rothko in affective, metaphysical, and symbolic terms, we are reminded in a case like this that his studio practice was grounded in material and formal considerations.

What, then, of those other terms? The literature on Rothko’s work is filled with names from the history of culture called upon as sources and models to help us account for meaning: Plato, Aeschylus, Michelangelo Buonarroti, Rembrandt van Rijn, William Shakespeare, Søren Kierkegaard, J. M. W. Turner, Friedrich Nietzsche, Stéphane Mallarmé, T. S. Eliot, Jean-Paul Sartre, and beyond—it is a long and distinguished list, including artists, writers, and composers (leaving aside anonymous sources and the Old and New Testaments). Indeed, such references were common among Rothko and his contemporaries of the New York School. During the late 1950s, Rothko claimed that his works engage grand themes—tragedy, ecstasy, and doom among them. His remark was intended to keep the paintings from being taken as strictly abstract exercises in color and form, implying instead that his works function in metaphorical and/or symbolic ways. In his account of the history of the interpretation of Rothko’s work, the art historian Glenn Phillips addresses the different forms of experience or states of mind that have been invoked by Rothko’s observers, according to whom the works have been variously characterized as “transcendental, tragic, mystical, violent or serene; as representative of the void; as opening onto the experience of the sublime; as exhilaratingly intellectual; or as profoundly spiritual—to mention just a few examples.” These things conflict, yet, as Phillips observes, each draws from the conviction that the work’s chief function is to intensify the process of seeing.6 It seems clear that Rothko meant to address large themes through subjective experience. In this regard, he said that the large size of his canvases instigates a direct, “intimate” physical relation of the painting to the observer.7 In turn, heightened seeing—or beholding—belongs to the realm of consciousness, and this is where form and process open other doors of apprehension.

Seeing in Rothko’s work is often described as a slowed process. Writing of the dark paintings, which arguably push this quality to an extreme, the art historian Briony Fer observes a “withholding of affect” that “entails a deferral in time.”8 (Similarly, Barbara Novak and Brian O’Doherty identify “two conflicting modes of Rothko’s practice” that come to late fruition in the dark paintings for the Houston chapel commission: “disclosure and withdrawal, the dialectic of his construction of mystery through equivocation.”9) A work like the Lang Collection painting can, of course, be perceived at a glance, but everything about it opposes an all-at-once apprehension. The thinness of the paint layer and the breadth of forms instigate a gradual perceptual commingling of figure and ground in shallow space. In this way, the painting is, at once, both empty and full, conjuring a condition of immanence. Speaking of the theorization of painting as a window, the art historian David Summers credits the Renaissance architect Leon Battista Alberti with an “extraordinary and original transformation of painting into a metaphor for our subjective experience of the world taken altogether.”10 Having abandoned Alberti’s window, a work of Rothko’s might be said to qualify as a site that now activates the subjective experience of painting taken altogether. With his work, Rothko devised a new way to activate color, value, surface, scale, and pictorial space as elements that now serve a direct encounter. In turn, these elements instigate a play of analogy that signifies deeper reserves.

Form, color, and value in Rothko’s work possess connotations of both weight and luminosity. In the Lang Collection painting, dark forms dwell in liminal obscurity. Set off by the work’s white form, a softly brushed nimbus-like slab with intimations of light and lightness, they exercise an almost gravitational pull. The size and format of the painting are enveloping, but the work’s physical limits are also clear. Displayed without a frame (which Rothko abandoned after the late forties), the painting wants to exceed itself and thereby belong to the actual space of the room, even as what occurs within it happens before us, not around us. The qualities I have enlisted—fullness, emptiness, suspension, extension, containment, weight—are both actual and metaphorical. The painting’s pictorial means can be described using these terms, yet those elements also figure ideas and sensations that charge the work’s potential for allegory. It must be said that vision already possesses such a charge, and that a Rothko painting allegorizes itself in this regard. It is a key achievement of Rothko’s work, perhaps culminating with the period of the Lang Collection painting, that an historical thematics of seeing—surface and depth, vision and touch, absence and presence, blindness and insight, desire and loss—can itself be said to hold the full range of connotations we associate with the work’s metaphysical depths.

Author

Jeffrey Weiss is an independent curator and critic living in Brooklyn, New York. He has held senior curatorial positions at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, where he organized the 1998 Mark Rothko retrospective exhibition, and at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York. Most recently, Weiss was coeditor and coauthor, with Francesca Esmay, of Object Lessons: Case Studies in Minimal Art (Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum / D.A.P., 2021).

Notes

1 There are various places to turn for a close material analysis of Rothko’s process, a large topic. Here, I will simply follow Briony Fer, who observed that Rothko distinguished his work from that of Ad Reinhardt, his contemporary, by referring to the exposed signs of touch on the surface of his works. “The difference between me and Reinhardt is that he is a mystic. By that I mean that his paintings are immaterial. Mine are here, materially. The surfaces, the work of the brush and so on. His are untouchable.” Quoted in Briony Fer, “Rothko and Repetition,” in Seeing Rothko, ed. Glenn Phillips and Thomas Crow (Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute, 2005), 170. The distinction between a primarily optical form of painting and a more openly or engagingly material one is useful. For an important descriptive account of Rothko’s paint surfaces, see David Anfam, Mark Rothko: The Works on Canvas (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 1998), 84–86; and for a close analysis of materials and techniques that contribute to Rothko’s complex paint surfaces, see Carol Mancusi-Ungaro, “Material and Immaterial Surface: The Paintings of Rothko,” in Mark Rothko, ed. Jeffrey Weiss (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1998), 282–301.

2 Anfam, Mark Rothko, 88–97.

3 Dore Ashton, About Rothko (New York: Da Capo, 1983), 130.

4 Mark Rothko, “Statement on His Attitude in Painting,” Tiger’s Eye, no. 9 (October 1949): 114.

5 Mark Rothko, Oral history interview with Katherine Kuh, 1983–84, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC.

6 Glenn Phillips, “Introduction: Irreconcilable Rothko,” in Phillips and Crow, Seeing Rothko, 1–9.

7 Mark Rothko, “A Symposium on How to Combine Architecture, Painting and Sculpture,” Interiors 110 (May 1951): 104.

8 Fer, “Rothko and Repetition,” 41.

9 Barbara Novak and Brian O’Doherty, “Rothko’s Dark Paintings: Tragedy and Void,” in Weiss, Mark Rothko, 274.

10 David Summer, Vision, Reflection, and Desire in Western Painting (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007), 13.

Explore the Collection

Sort by Chronology

Sort by Artist

Sort by Author

Franz Kline, Painting No. 11, 1951

Acquired November 13, 1970

Mark Rothko, Untitled, 1963

Acquired May 18, 1972

Robert Motherwell, Before the Day, 1972

Acquired October 12, 1972

Adolph Gottlieb, Crimson Spinning #2, 1959

Acquired December 11, 1972

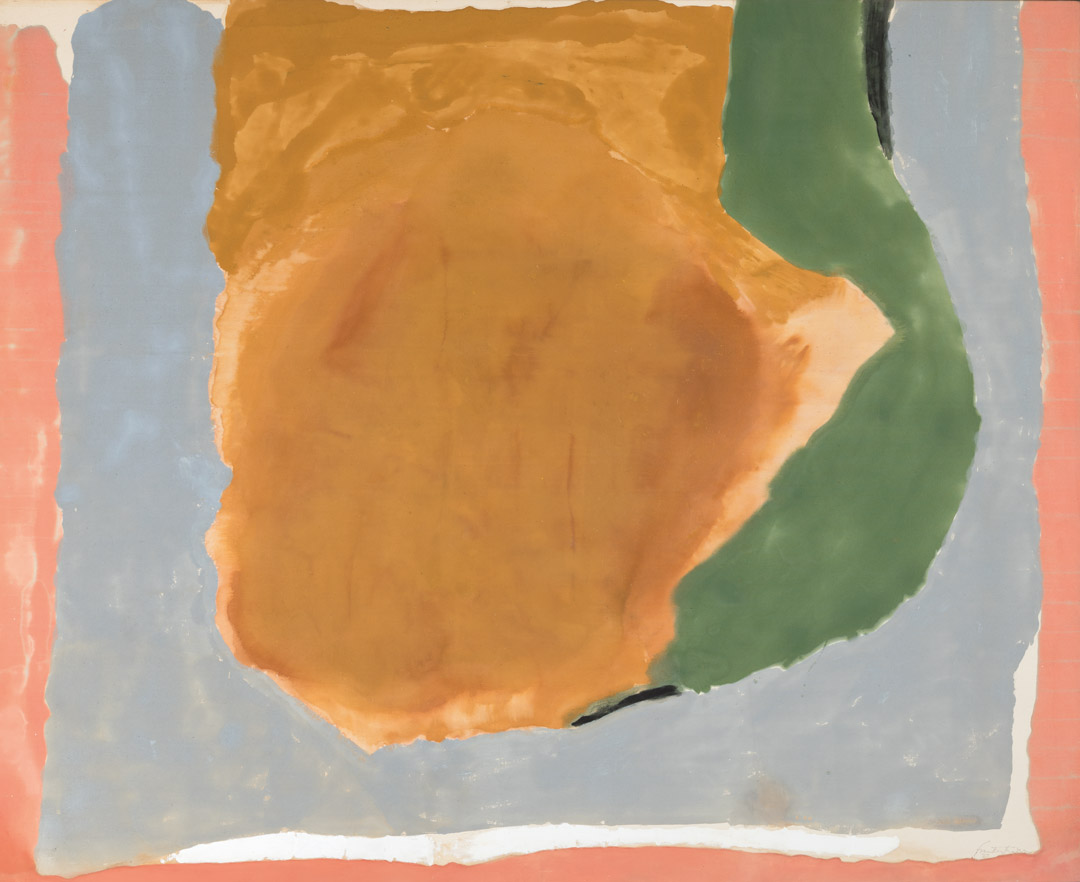

Helen Frankenthaler, Dawn Shapes, 1967

Acquired April 26, 1973

Clyfford Still, PH-338, 1949

Acquired November 10, 1973

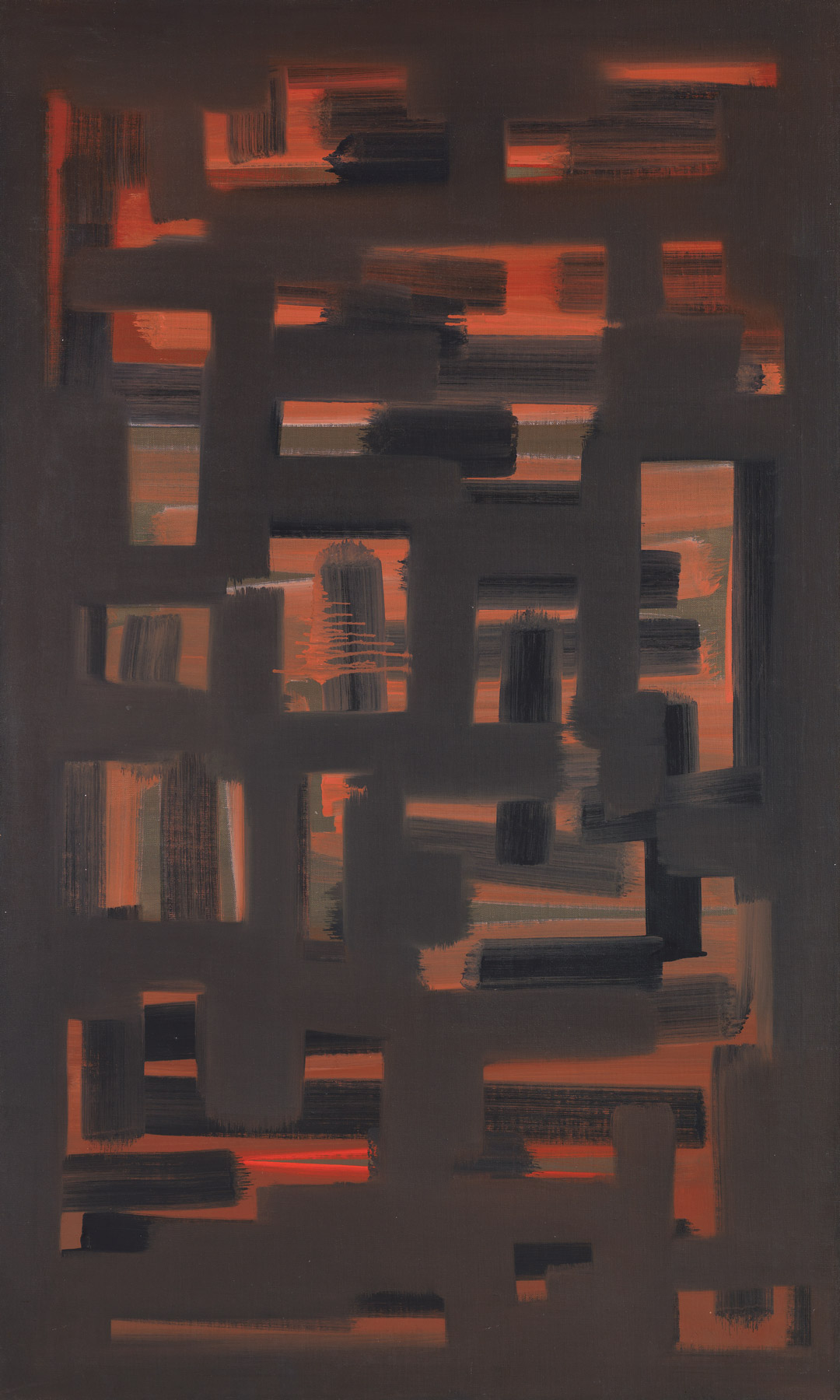

Ad Reinhardt, Painting, 1950, 1950

Acquired January 8, 1974

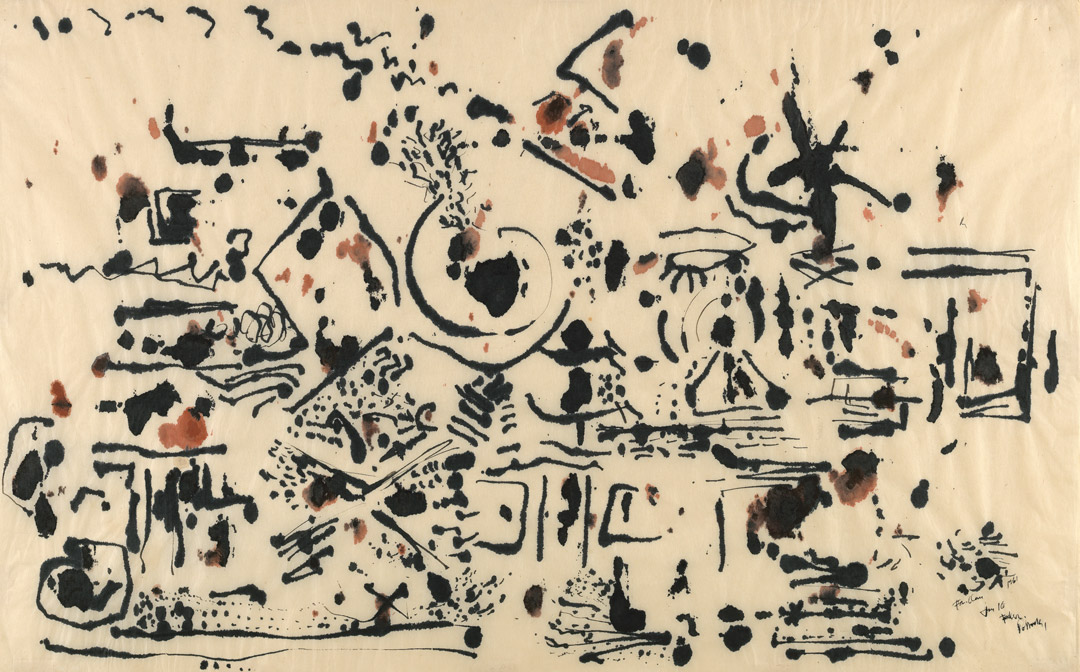

Jackson Pollock, Untitled, 1951

Acquired March 29, 1974

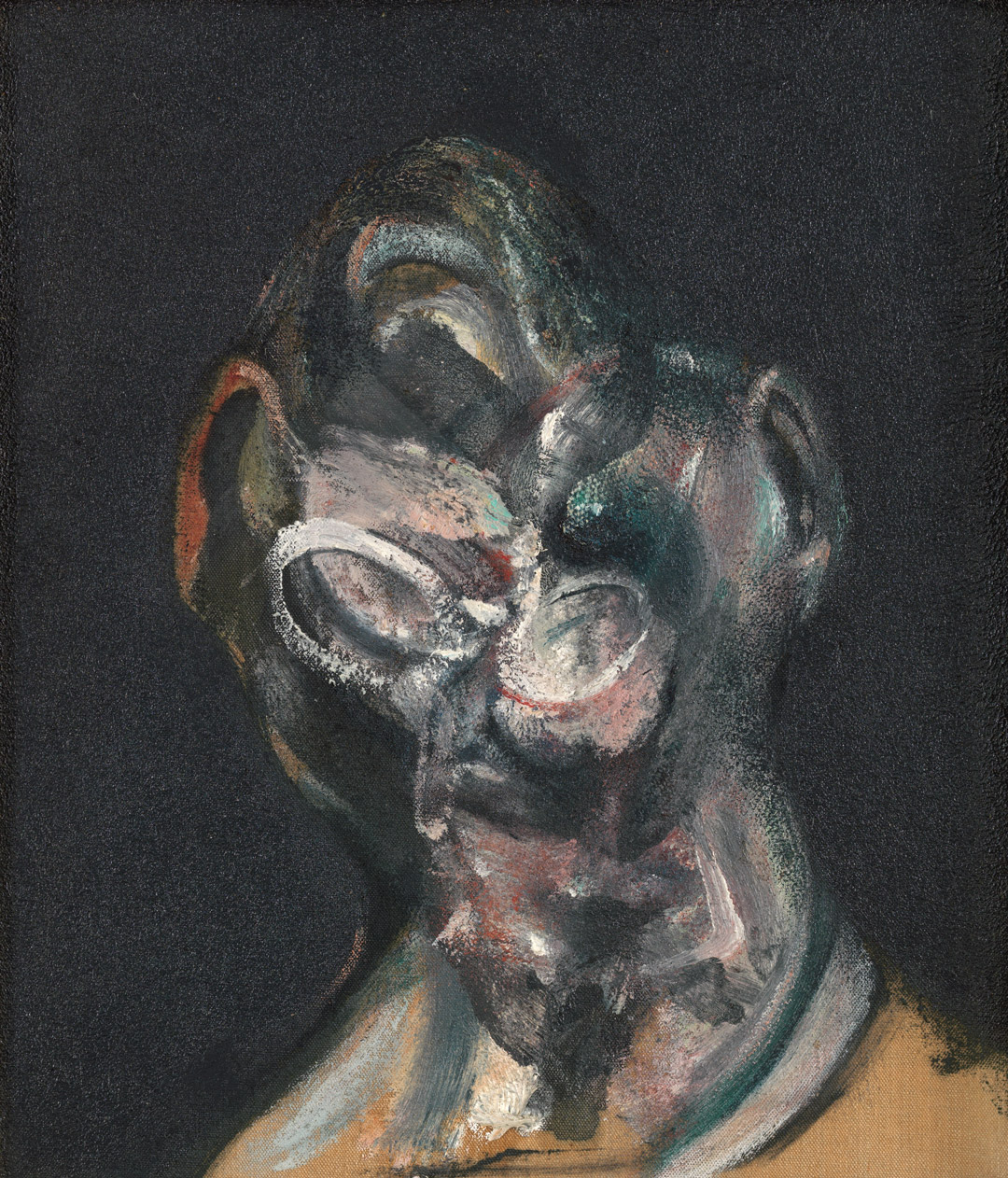

Francis Bacon, Portrait of Man with Glasses I, 1963

Acquired October 24, 1974

Alberto Giacometti, Femme de Venise II, 1956

Acquired January 2, 1975

Robert Motherwell, Irish Elegy, 1965

Acquired November 7, 1975

Francis Bacon, Study for a Portrait, 1967

Acquired November 20, 1976

Willem de Kooning, Town Square, 1948

Acquired December 6, 1976

Joan Mitchell, The Sink, 1956

Acquired September 12, 1977

David Smith, Cubi XXV, 1965

Acquired February 22, 1978

Philip Guston, To B.W.T., 1952

Acquired February 14, 1979

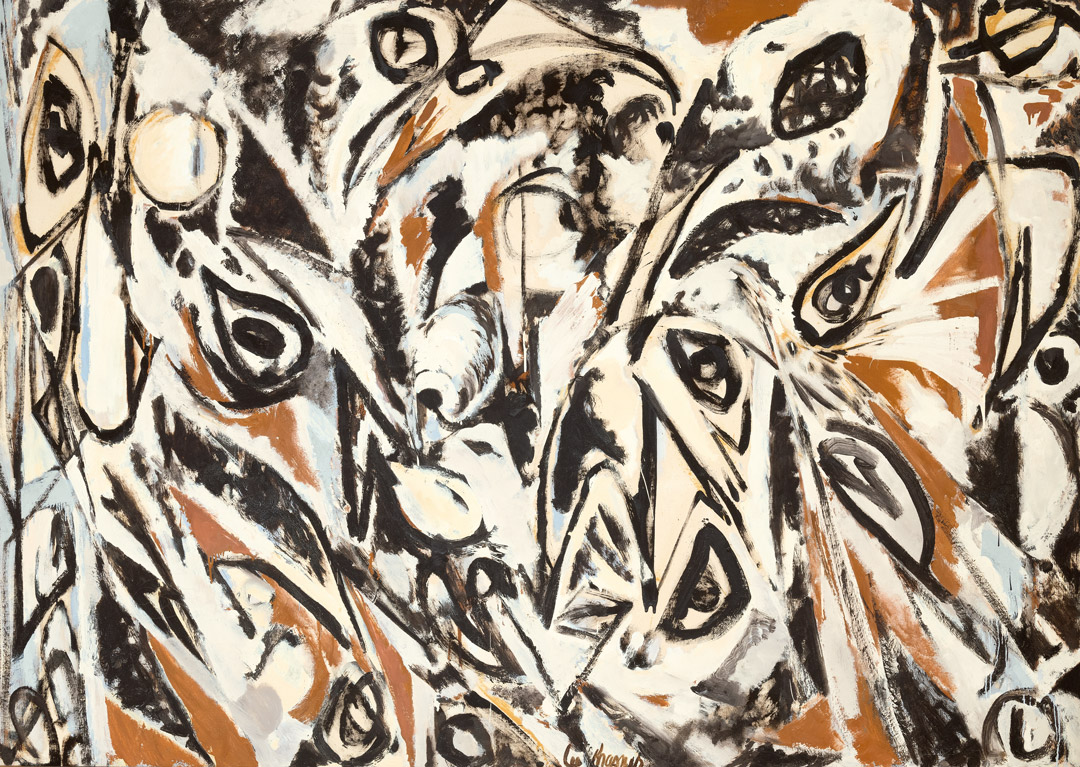

Mark Rothko, Untitled, ca.1945

Acquired November 12, 1980

Lee Krasner, Night Watch, 1960

Acquired November 19, 1981

Philip Guston, The Painter, 1976

Acquired February 1, 1982