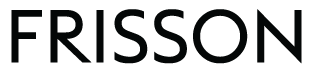

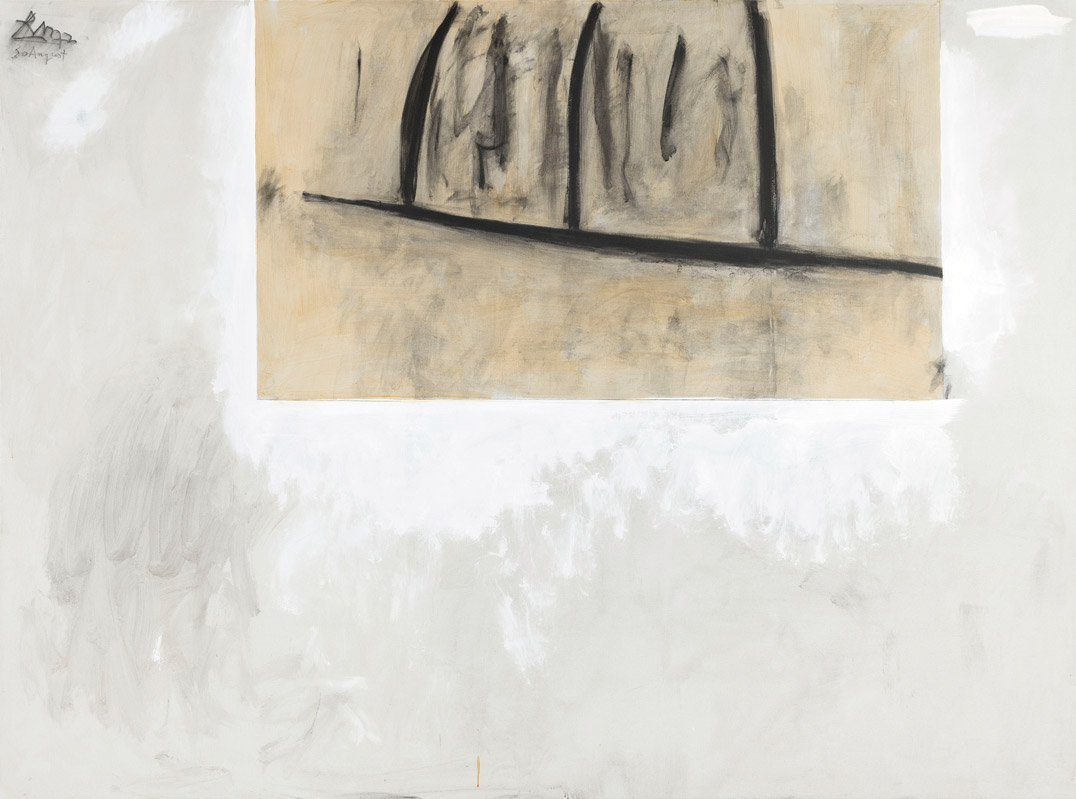

Untitled

ca. 1945

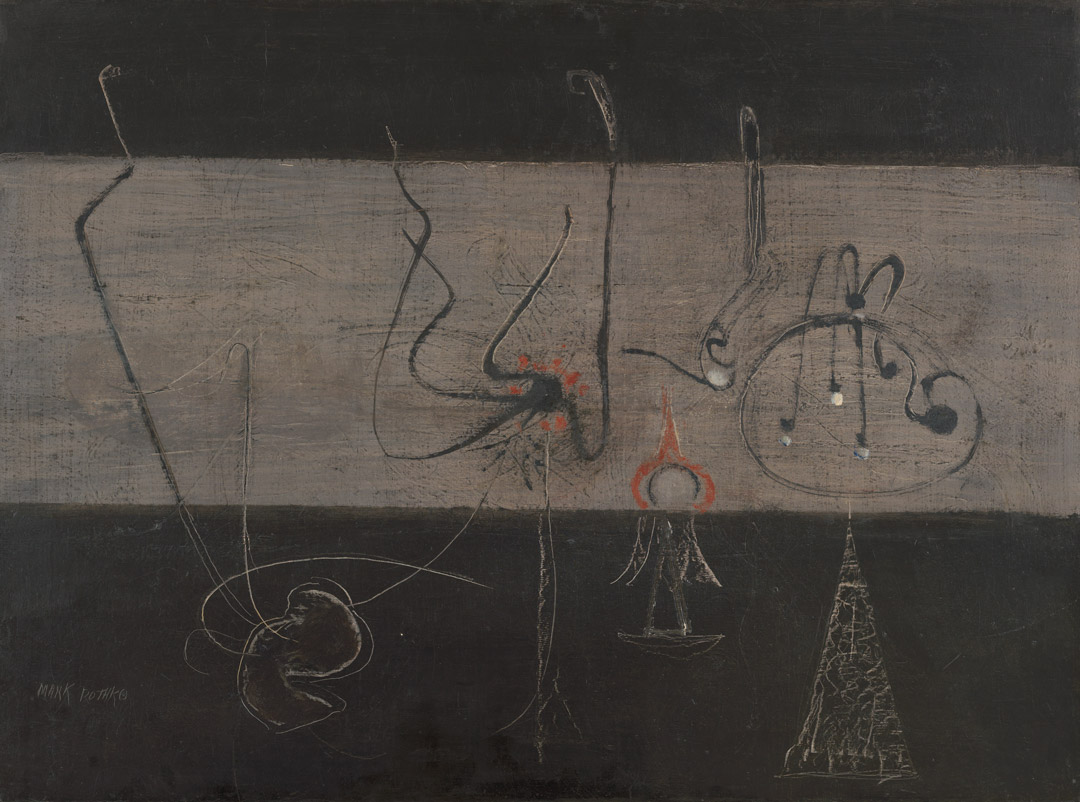

Mark Rothko

American, born Russia (now Latvia) (1903–1970), oil on canvas, 22 1/2 × 30 3/8 in. (57.1 × 77 cm). Seattle Art Museum, Gift of the Friday Foundation in honor of Richard E. Lang and Jane Lang Davis, 2020.14.3. Photo by Spike Mafford / Zocalo Studios. Courtesy of Friday Foundation. © 2021 The Mark Rothko Estate / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Untitled

Jeffrey Weiss

According to David Anfam, author of the catalogue raisonné of Mark Rothko’s paintings, the untitled Lang Collection painting of ca. 1945 is one of “three small oils at $150” recorded in a handwritten checklist of the artist’s exhibition at the Betty Parsons Gallery in 1947.1 (The others belong, respectively, to the collection of Christopher Rothko, the artist’s son, and the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC.) Together, the three works form an obvious group: identical in size, they all display a division of the pictorial field into three horizontal bands that alternate in value such that the center one is lighter than those on the top and bottom. The other two paintings are cool gray-blue in tonality, while the palette of the Lang Collection painting is warm—rosy gray in the center and dark gray-black in the upper and lower areas. Otherwise, the works share a repertoire of biomorphic glyphs that typify Rothko’s work during the early to mid-1940s, although here they are smaller and more delicate than usual in relation to the composition overall, making the three paintings distinctively fragile and refined.

This repertoire comes from an inventory of images and motifs that occur throughout paintings of the forties by Rothko and his New York School contemporaries (and can be traced into the fifties in works by artists of the New York School’s second wave). As a quasi-abstract manner, biomorphism derived from the example of Surrealism in Europe, especially visible in the New York gallery scene (and elsewhere across the country, including the West Coast and the desert Southwest) thanks to the emigration of a number of artists from Europe to the United States during World War II. Biomorphism was spawned by automatism, the cursive drawing style developed in Surrealist circles in Paris during the 1920s, which was understood to reflect, almost seismographically, the shifts and tremors of subconscious thought—a presumably free play of associations literally drawn from the depths of the subject’s psyche. Transformed into the decidedly conscious underpinning for a new form of advanced painting by André Masson and Joan Miró, among others, this organic linearity generated a variety of forms that analogize the human subconscious to growth and change in the natural world. In postwar New York, this body of images came to be linked to what was characterized in certain anthropological and literary circles of the time as the metaphysical recesses of prehistoric, archaic, and tribal imagination—presumably, the domain of the premodern, precivilized mind. In that context, biomorphic imagery, both abstract and representational, signified a pseudoprimeval mythography through which matter and spirit are shown to merge. In the wake of the war, painters in search of forms of meaning that circumvent the belief systems of the modern world awarded particular significance to Carl Jung’s theories of the collective unconscious. With Jung’s model in mind, biomorphic forms share iconographical space in their work with the schematic representation of other things—hieratic birds, floating eyes, gates, portals, and cosmological signs as well as masks, totems, and other tribal artifacts of the Pacific Northwest—that are taken to signify rituals and ceremonies of procreation, sacrifice, and death, which were said at the time to compose the primal underpinnings of Greek myth.2

Rothko’s work on canvas and paper took this form throughout the early to mid-forties. These pictures often possess evocative titles featuring phrases such as archaic fantasy, primeval landscape, votive figure, hierarchical birds (fig. 1), and the like, as well as references to specific figures from history, myth, and religion including Lilith, Antigone, and Tiresias. By late 1946, his approach had begun to shift: titles were dropped and shapes became increasingly abstract, ultimately spreading across the surface in a long sequence of paintings of 1947–48 known as Multiforms.3 It would be wrong, however, to ascribe purely iconographical interest to the earlier works. To begin with, their symbolic ambitions remind us that the paintings of the fifties and sixties were themselves claimed by Rothko to encompass themes belonging to the history of myth and psyche in Western culture, although the artist’s means had, by then, dramatically changed. Moreover, Rothko’s pictures of the post-Surrealist period also show the origin of formal and technical devices that served his pursuit of a more radical, absolute kind of painting.

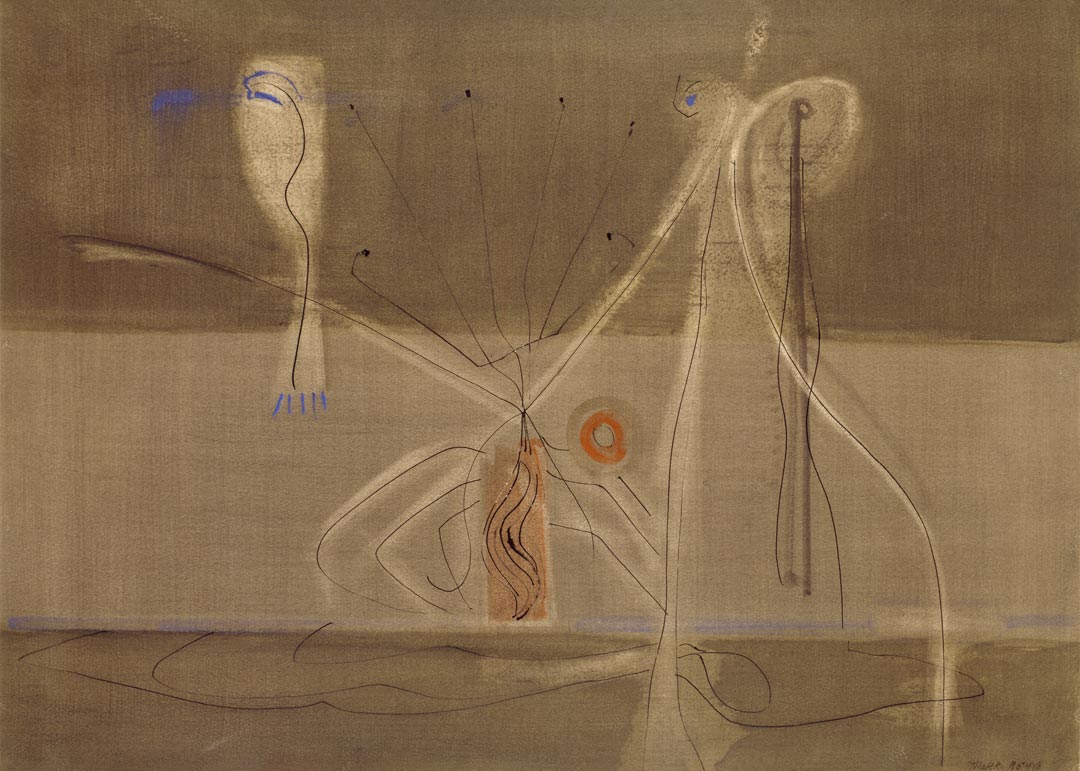

So much of Rothko’s work of the early mid-forties, including the untitled Lang Collection painting, demonstrates a consistent division of the pictorial surface into two or three horizontal areas or zones before, within, or across which his motifs are lodged. In most instances, the paintings show a distinct figure-ground relation between the motifs and the divided space. Yet the “ground”—the horizontal bands—clearly anticipates the turn that Rothko’s work took in 1949: the emergence of two or three “stacked” rectangular forms. Those forms rarely extend from edge to edge the way the early bands do, but they often almost fill the surface, replacing the figure-ground relation of the earlier works with fields in which figure and ground almost merge. Even so, the resemblance between the bands of the forties and the stacked forms of Rothko’s work of the following two decades is noteworthy. Its early application is intermittent, but it represents one solution to a pictorial problem—the noncompositional animation of the plane—to which Rothko would return.

While the division of the picture plane into two or three horizontal bands was a chief formal device in Rothko’s work of the forties, it possessed clear symbolic value. Quite apart from the iconography of life forms, totems, and glyphs, the division in and of itself implicates strata, in the geological and/or archeological sense. In this way, it figures formation in time. (The idea was shared among many disciplines. The psychoanalytic writings of Sigmund Freud, for example, are filled with metaphors of stratification drawn from geology and archeology.4) We can, therefore, identify planar partition as a kind of symbolic form, an idea that has a direct bearing on Rothko’s work after 1949, by which time biomorphic imagery had been abandoned and content was solely borne by multiple liminalities of form, color, value, and pictorial space. In the artist’s later paintings, the metaphorical connotations of the early format are not eliminated but absorbed. At stake, in this regard, is the temporal significance of stratification: its allusion to that which lies below and comes before, and its intimations of gravity and space—of phenomena that are heavy, deep, hidden, or obscure.

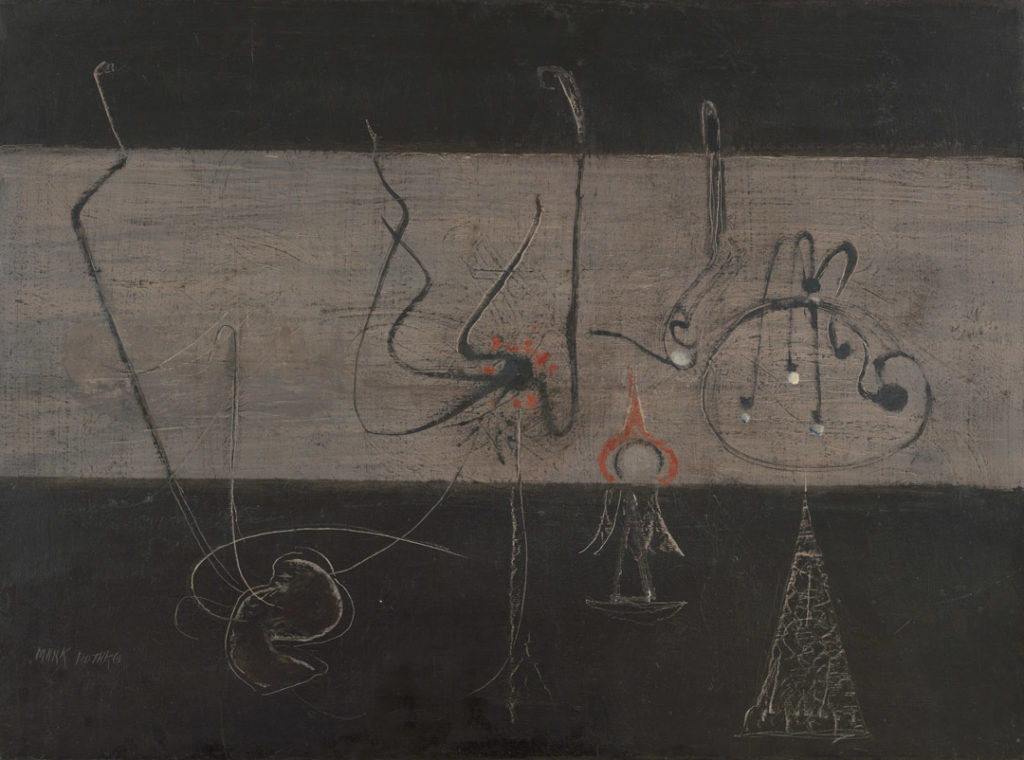

Other qualities of the Lang Collection painting include separate factors of importance to the development of Rothko’s work. For example, the painting demonstrates an extremely subtle deployment of luminous grays, which suffuse the image with a soft, smoky half-light, a quality that anticipates the optical nuances of works to come. The flatness of Rothko’s partition of the plane supports a second, equally significant element: a material distillation of means. Simply put, during this period Rothko first began applying paint in thin layers. In certain works, including the Lang Collection painting, some areas are conspicuously wash-like in their transparency, others scraped down. These methods in oil are closely related to works of this kind in watercolor and gouache on paper, for which the medium is already inherently thin: there, Rothko can be seen experimenting with the spread of medium on and within the sheet. It is worth noting that the “three small oils” at the Parsons gallery resemble various works on paper of exactly the same dimensions and, almost certainly, the same date (fig. 2), suggesting an open equivalence between paper and canvas in this regard. The equivalence is not to be underestimated, for, notwithstanding the relatively small dimensions of the early works on both supports, this process of paint application was fundamental to the diaphanous surface qualities and expansive breadth of the paintings of Rothko’s so-called classic period.

Author

Jeffrey Weiss is an independent curator and critic living in Brooklyn, New York. He has held senior curatorial positions at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, where he organized the 1998 Mark Rothko retrospective exhibition, and at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York. Most recently, Weiss was coeditor and coauthor, with Francesca Esmay, of Object Lessons: Case Studies in Minimal Art (Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum / D.A.P., 2021).

Notes

1 David Anfam, Mark Rothko: The Works on Canvas (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1998), cat. no. 269.

2 For an exhaustive overview of Rothko’s early thematic concerns in the context of New York School painting in general, see

3 For the dropping of evocative titles, see Anfam, Mark Rothko, 57.

4 See Ernest S. Wolf and Sue S. Nebel, “Psychoanalytic Excavations: The Structure of Freud’s Cosmography,” American Imago 35, no. 1–2 (Spring–Summer 1978): 178–202.

Explore the Collection

Sort by Chronology

Sort by Artist

Sort by Author

Franz Kline, Painting No. 11, 1951

Acquired November 13, 1970

Mark Rothko, Untitled, 1963

Acquired May 18, 1972

Robert Motherwell, Before the Day, 1972

Acquired October 12, 1972

Adolph Gottlieb, Crimson Spinning #2, 1959

Acquired December 11, 1972

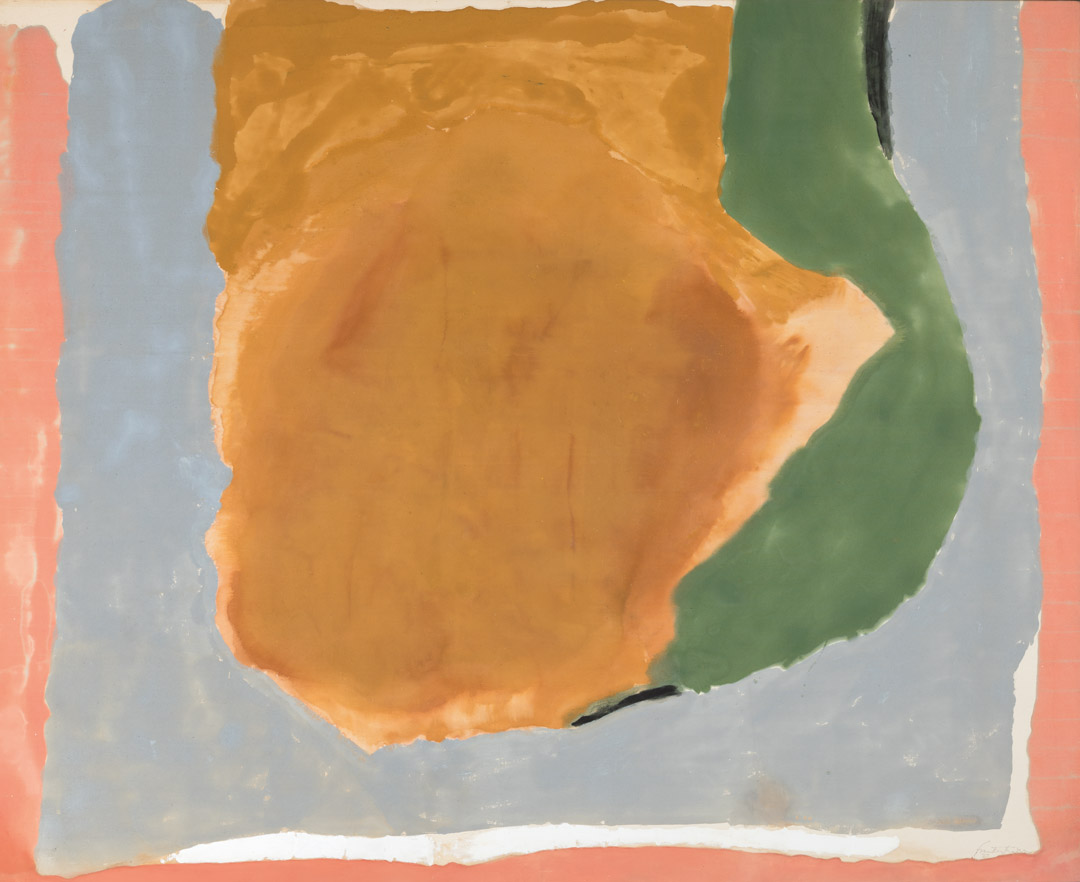

Helen Frankenthaler, Dawn Shapes, 1967

Acquired April 26, 1973

Clyfford Still, PH-338, 1949

Acquired November 10, 1973

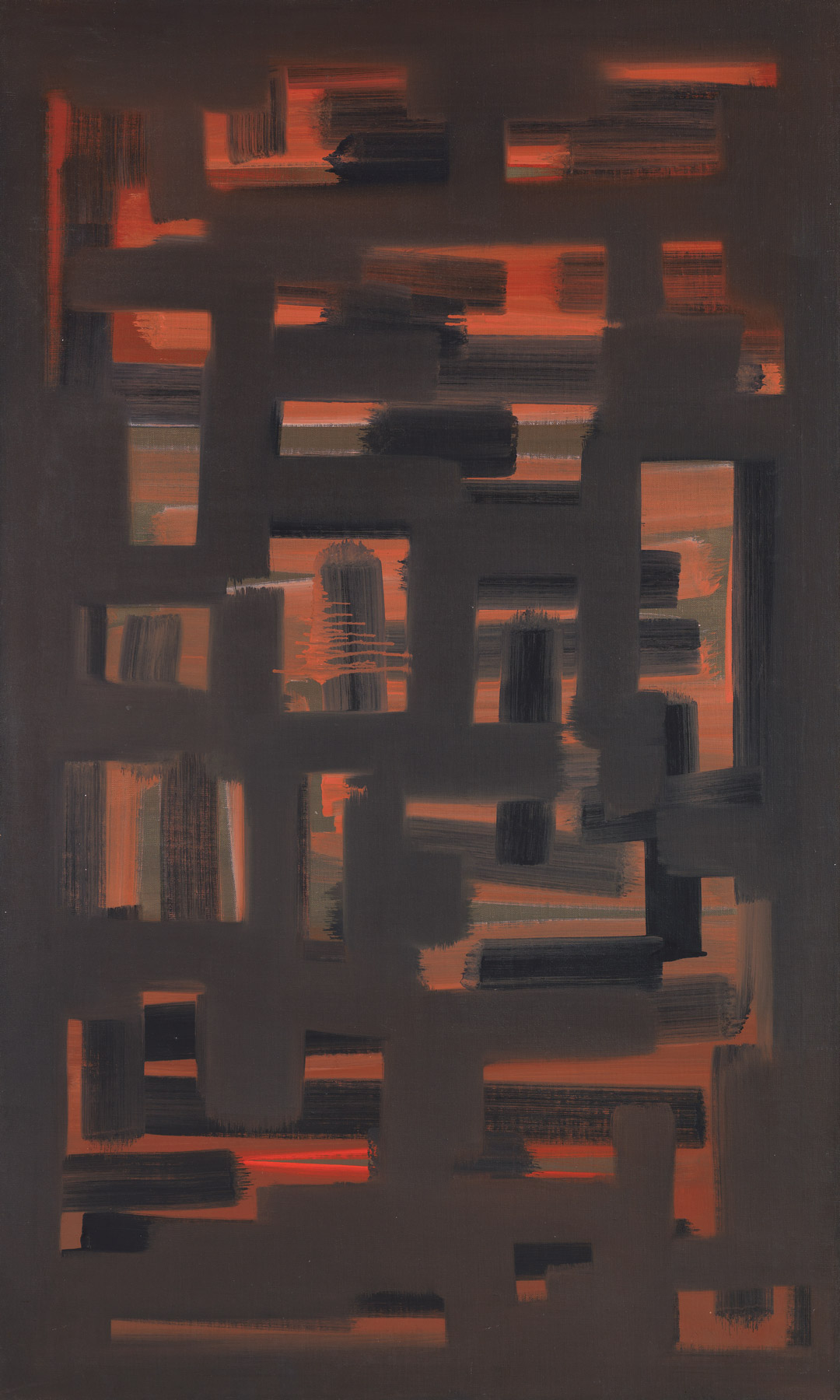

Ad Reinhardt, Painting, 1950, 1950

Acquired January 8, 1974

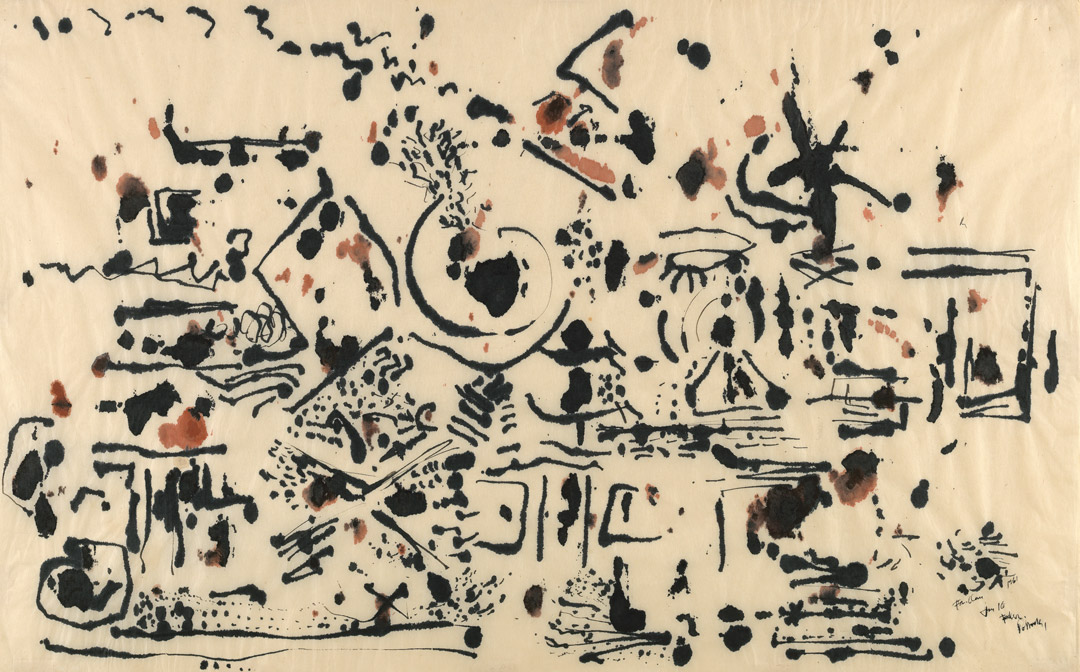

Jackson Pollock, Untitled, 1951

Acquired March 29, 1974

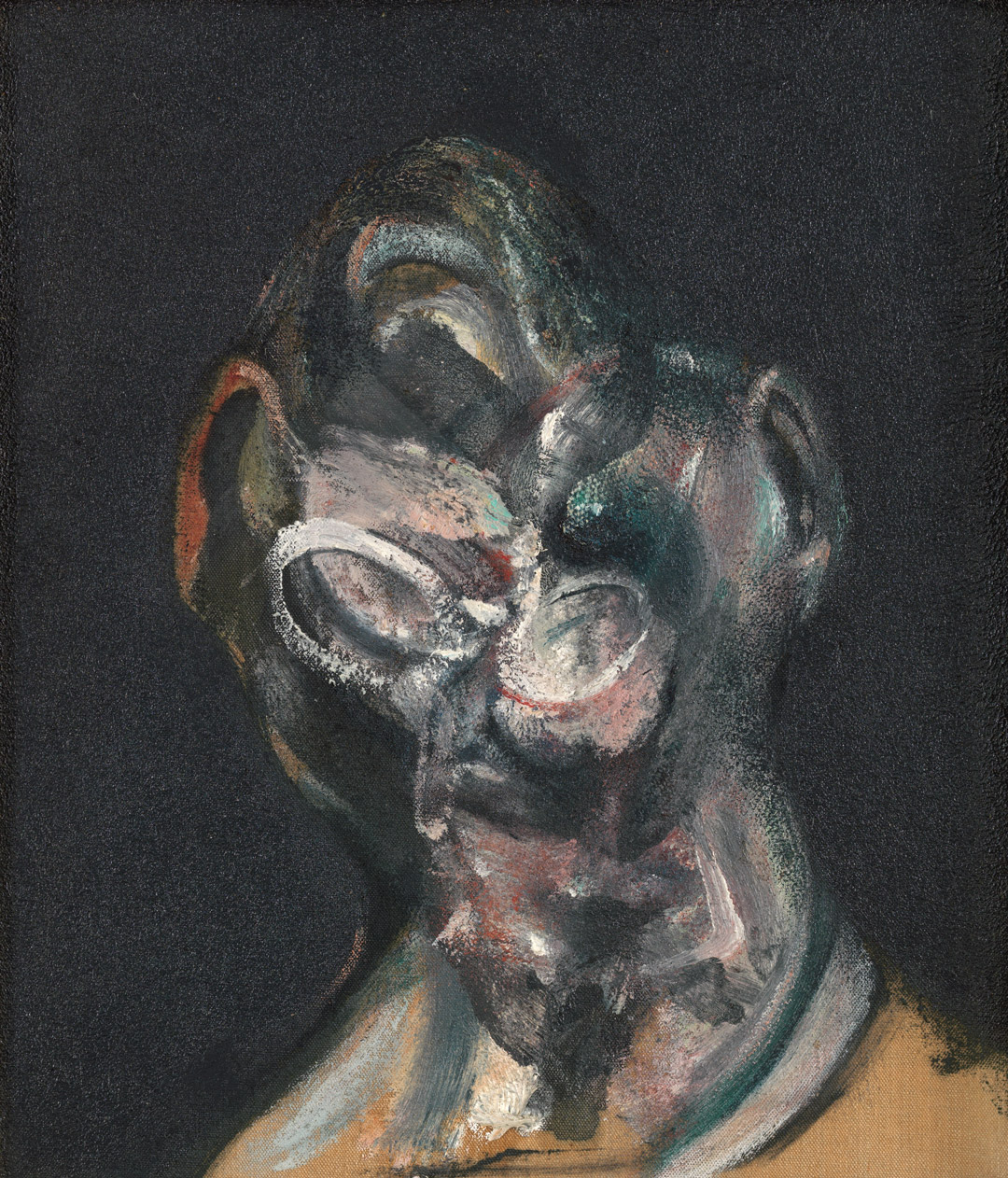

Francis Bacon, Portrait of Man with Glasses I, 1963

Acquired October 24, 1974

Alberto Giacometti, Femme de Venise II, 1956

Acquired January 2, 1975

Robert Motherwell, Irish Elegy, 1965

Acquired November 7, 1975

Francis Bacon, Study for a Portrait, 1967

Acquired November 20, 1976

Willem de Kooning, Town Square, 1948

Acquired December 6, 1976

Joan Mitchell, The Sink, 1956

Acquired September 12, 1977

David Smith, Cubi XXV, 1965

Acquired February 22, 1978

Philip Guston, To B.W.T., 1952

Acquired February 14, 1979

Mark Rothko, Untitled, ca.1945

Acquired November 12, 1980

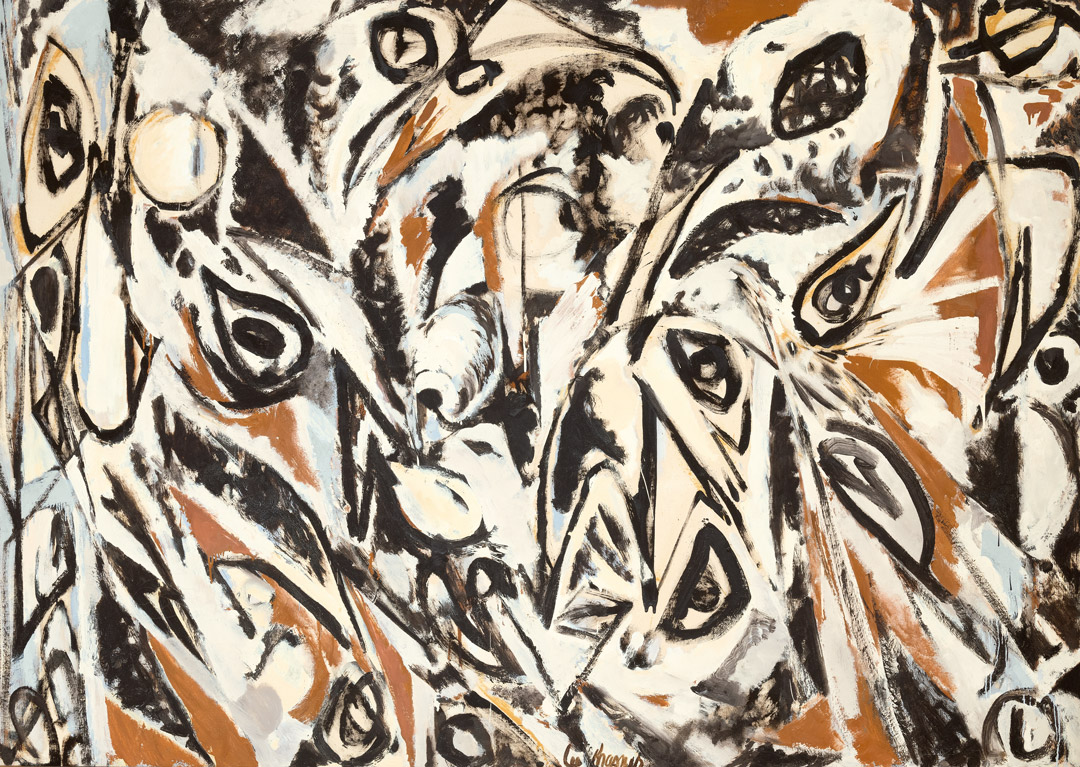

Lee Krasner, Night Watch, 1960

Acquired November 19, 1981

Philip Guston, The Painter, 1976

Acquired February 1, 1982